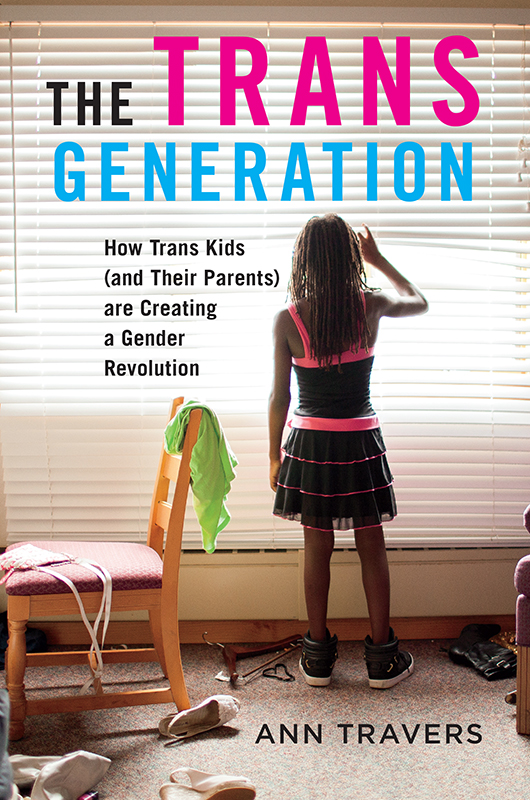

The Trans Generation

The Trans Generation

How Trans Kids (and Their Parents) Are Creating a Gender Revolution

Ann Travers

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2018 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Travers, Ann, author.

Title: The trans generation : how trans kids (and their parents) are creating a gender revolution / Ann Travers.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017054995 | ISBN 9781479885794 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Transgender children. | Parents of transgender children. | Transgender peopleIdentity. | Gender identityLaw and legislation.

Classification: LCC HQ77.9 .T71525 2018 | DDC 306.76/8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017054995

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To every kid and every parent that I interviewed: Thank you. You are the beating heart of this book.

Contents

People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they dont know is what what they do does.

Michel Foucault

February 17, 1962: Toronto, Ontario. In the hospital, the doctor, in the usual way, tells my unwed mother, Its a girl. Fifty-five years later, I bear both the psychological scars of the effects of the branding of me as a girl and eventual woman and the wrenching separation from my birth mother. In the story I tell about myself, I am unable to separate the sex assignment imposed on me from the sexism and misogyny that were my due as a girl or from the gender policing and homo-hatred I received for not being very good at it. Nor, for that matter, can I untangle the privilege of my whiteness and relative wealth from the patriarchal burden of shame imposed on unwed mothers and their offspring and my own bad luck in the adoption game. I come from all these things. These social forces are real; they shape opportunities unequally. I am all these things and more.

My daughter and I recently discussed the lack of agency that children typically experience: most kids do not have much say in many things, and all have absolutely no control over how they come into this world (out of whose body, in what place and time) or typically who raises them and how. We are all born into systems of power and privilege, and this concept of the sociological imagination, as C. Wright Mills famously coined it, has a significant impact on our life chances and choices. Our biographies are shaped by our lived experience in specific geopolitical and historical moments. Context is not everything, but it certainly counts for a lot.

Being called a boy or a girl and assigned correspondingly gendered names and pronouns are two of the many dimensions of power Parents are expected to do gender work with their children properly. Some, such as Storms parents, Rogue Witterick and David Stocker, make efforts to resist sex stereotyping by choosing gender-neutral names and resisting the efforts of others to assign gendered clothing, characteristics, and activities to their children on the basis of their assigned birth sex; but the binary sex system is so pervasive that most children succumb, and those who do not typically struggle for support.

I define transgender in a broad and historical sense to include people who defy societal expectations regarding gender. Trans activist Julia Serano notes that not everyone who falls under this umbrella will self identify as transgender, but all are viewed by society as defying gender norms in some significant way. While Serano and others distinguish between those who are transsexualindividuals who transition from their assigned sex to their affirmed sexand those who are transgender, the issue of terminology is complicated because individuals understandably have very strong feelings about how they identify. I use the term transgender and its shorthand, trans, interchangeably to speak in very general terms about kids who defy gender norms, but I choose each persons own language to describe them specifically.

I have been traveling in ethnographically rich circles, both socially and as a researcher, offline and online, formal and informal, with transgender kids and their families for over seven years. This book is fairly unique in that I rely on the direct reports of trans kids and their parents to map in time and space the ways in which they are disabled

Children do have strong feelings about their gender identities, so I draw on the embodied experiencethe sufferingof my participants in navigating the gendered spaces that disable them as well as the pleasure and empowerment they experience in resisting the dominant narratives that restrict their sex/gender identities and expression. But the perspectives of parents, while not synonymous with those of their children, are very important because they are typically their childrens primary adult attachment, and it is parents who most often advocate on their behalf.

For the purposes of this book, childhood is defined as an institutionalized stage of life from birth to the age of majority (which varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction across Canada and the United States from 18 to 21 years of age). In discussing the experiences of specific young people, this text uses the term children to refer to those 15 years of age and younger, youth to refer to those between the ages of 16 and 21, and kids to speak more generally about people 18 and under.

My research confirms that trans kids resist the very names and pronouns associated with the sex category that has been assigned to them at birth, which puts them in potential conflict with families, peers, school and sports/recreational institutions and programs, healthcare systems, juvenile justice systems, organizations that provide social support, and work environments. All children do gender work, but the gender work that trans kids do to resist the sex/gender identity assigned to them is particularly powerful in its ability to make the social construction and imposition of binary sex and gender systems more visible. The experiences of trans kids also throw into sharp relief the extensive labor that the people in their environments engage in to impose and naturalize cisgender binary categorization.

Many of the trans kids in my study regularly experience crisis as a result of the restrictive ways in which sex categories regulate their daily lives and put pressure on them to deny their internal sense of who they but relationships with sex-defined peers, sex-segregated/sex-differentiated activities and spaces, gender-coded clothing and hairstyles, pronouns and names, access to healthcare, and gender policing by adults and peers also play a significant role. This perspective is reflected in the experiences of many of the kids and parents I spoke with.

Next page