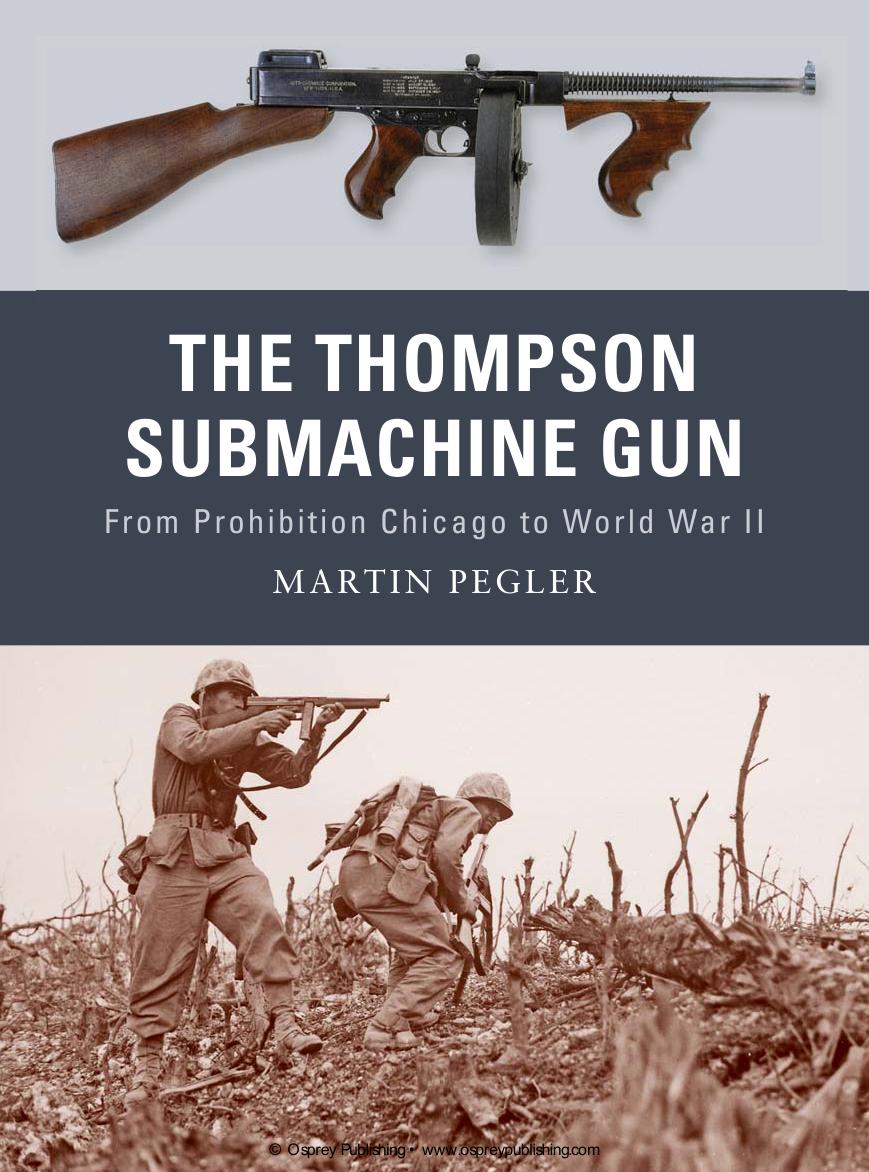

THE THOMPSON SUBMACHINE GUN

MARTIN PEGLER

INTRODUCTION

The deadliest weapon, pound for pound, ever devised by man. Time magazine, December 1939

There are certain firearms that developed an iconic status during the last century. Partly this is due to the war and gangster films that became popular during the 1900s, many of which gave prominence to particular guns. The guns were not necessarily chosen because they were the best weapons in use at the time, but more often because of their form rather than their function; in short, some guns simply looked better than others, regardless of their mechanical properties or historical accuracy. As a result, collectors and shooters wanted the guns they saw on screen. A fairly modern example of this effect can be found in the use of the Smith & Wesson (S&W) .44 Magnum in the Dirty Harry series of films in the 1970s and 1980s. The films sparked a colossal demand for the revolvers, a demand that S&W was initially unable to meet, and which arguably saved the company from looming financial disaster. Another example comes from the increased screening of live TV combat footage pioneered during the Vietnam War. Ordinary citizens could actually see soldiers holding and using various modern assault rifles and machine guns, and this sparked a renewed interest in weapons technology. Whereas older military firearms had always been in demand by collectors, there soon arose a parallel interest in the weapons currently in use, so commercial variants of the M-16, AK-47 and others became much in demand. The Thompson submachine gun is one of these iconic weapons. It had an unusual beginning, for it was developed after World War I as a trench weapon, but the war ended before it could see service. It was taken up with some enthusiasm, however, by the criminal fraternity working in Chicago and New York during the Prohibition years of the 1920s. The police and Bureau of Investigation, finding themselves out-gunned, were forced to purchase the Thompson for law-enforcement use. The huge publicity it gained in pitched battles between gangsters and police, and through its use in the notorious St Valentines Day massacre (14 February 1929), quickly came to the attention of Hollywood producers, who began to feature it in a large number of films. In fact, the Thompsons film appearances were out of all proportion to its actual street use, and under normal circumstances it would probably have faded from view during the late 1930s, as increasingly efficient policing signalled the demise of the gangs.

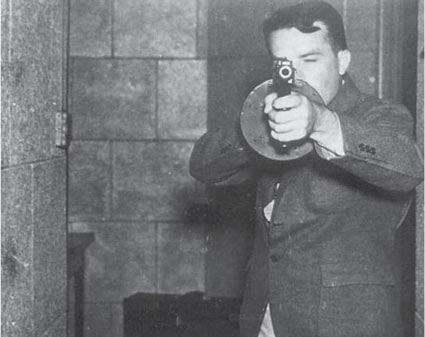

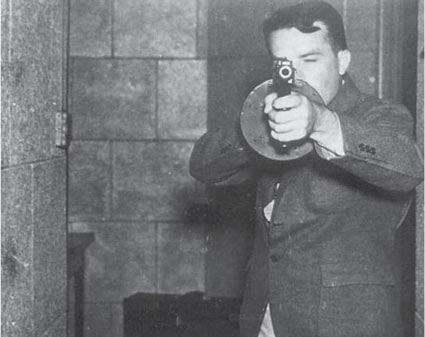

The two stars of the 1932 gangster film Scarface, Paul Muni and the Thompson M1921. It was Hollywood that gave the Thompson its fame, but it would be nearly another decade before World War II gave it its place in military history. (Photo by John Kobal Foundation/Getty Images)

Yet history has a way of coming full circle. In the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, America had to arm itself quickly to fight a totally unexpected war. There was little in the US arsenal at that time that had not been in use during or immediately after World War I, but fortuitously the brilliant John Garand had been working on a new design of semi-automatic rifle, the M1 Garand, since the early 1930s, and it had been accepted for service in 1936. Despite the fact that the concept of submachine guns had never been particularly attractive to the US Army, and the Thompson had not been widely adopted for military service, it was at least commercially available. It thus became an obvious choice for the army and Marine Corps to help arm its troops alongside the M1 Garand, and eventually the Thompson, or Tommy gun as it was universally known, became the most famous Allied submachine gun of the war. Indeed, Auto-Ordnance, the Thompsons manufacturer, was quick to see the importance of this nickname, and they patented it.

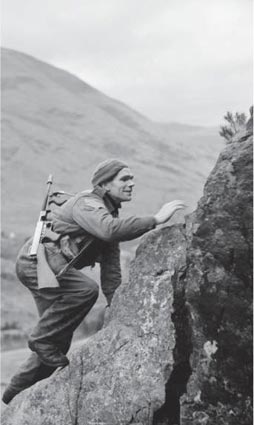

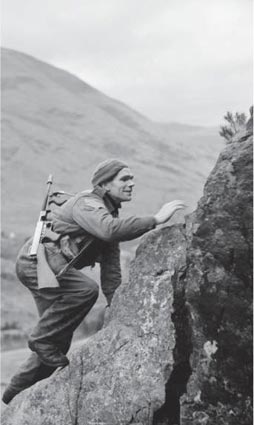

A soldier from No. 1 Commando, armed with a Model 1928A1 Thompson, climbs up a steep rock face during training at Glencoe in Scotland. Although the receiver of the Thompson looks polished, it is merely catching the light, one reason for the later adoption of non-reflective Parkerising. (IWM H 15667)

The Thompson was carried by American, British, French, Indian, Australian, Canadian, South African, New Zealand, Soviet and Chinese troops throughout World War II. It saw combat in every possible type of terrain desert, mountain, jungle and forest, field and street and it proved utterly competent in them all. The men who carried the Thompson swore by it and occasionally at it, as it was by no means perfect, but those who were issued with the gun seldom gave it up willingly. The firepower generated by its heavy .45-calibre bullets was second to none, and in closecombat situations a burst from a Thompson would usually resolve the situation immediately and very satisfactorily. Few on the receiving end of a burst from a Thompson ever lived to tell the tale. The story of how it achieved this status is both convoluted and fascinating, and begins in the trenches of France and Flanders in late 1917.

DEVELOPMENT

A one-man, hand-held machine gun

THE ORIGINS OF THE THOMPSON

The trench combat of the Great War spawned a number of weapons that were unique to the conflict and have since become commonplace on the battlefield: hand grenades, sniping rifles, flamethrowers, light mortars and submachine guns. But it was Germany who pioneered the first practical design of what was originally called the Maschienpistolen, or machinepistol, but is now referred to as the submachine gun, and this was the 9mm Bergmann MP18/1. The Germans quickly realized during the grim fighting for Verdun in 1916, that bolt-action rifles suffered from severe limitations in trench warfare. They were too long, cumbersome to carry, slow to shoot and reload, and actually too powerful: in trench warfare, where combat ranges seldom exceeded 200 yards (183m) and were frequently almost point-blank, a rifle with a theoretical range in excess of 2,000 yards (1,828m) was quite unnecessary. A short-range, rapid-firing weapon with a large magazine capacity was what was needed, so the development of the Bergmann became a landmark in firearms design. Some 30,000 were issued between late 1916 and 1918, and it was subsequently copied by dozens of other countries. The MP18/1 suffered from a few shortcomings, the main problem being the use of the unreliable Luger snail-drum magazine, soon replaced by a simple box magazine, but in general it performed superbly. The term submachine gun arose from the weapons use of a sub-rifle calibre cartridge, generally a pistol calibre round, and the fact that it was capable of fully automatic fire.

The Allies were aware of the need to improve infantry weapons for trench combat, but British soldiers were not thought trustworthy enough to be issued with a personal automatic weapon. It was commonly assumed by the British military hierarchy that Tommies would fire off every cartridge within seconds, leaving themselves helpless. In addition, in wartime few governments were willing to introduce any large-scale form of new technology, as industrial production was invariably straining to supply sufficient weapons and equipment to keep the war machine going. Ironically, it was the French, who had a tradition of producing outdated, poorly performing small arms, who introduced the concept of increased personal firepower with the introduction during World War I of the truly awful Chauchat light machine gun, and the slightly more efficient Fusil Mitrailleur Modle 1917, a gas-operated five-shot semi-automatic rifle. Neither were exactly compact or light, but the basic concept behind them, of providing troops with additional firepower, was a sound one.