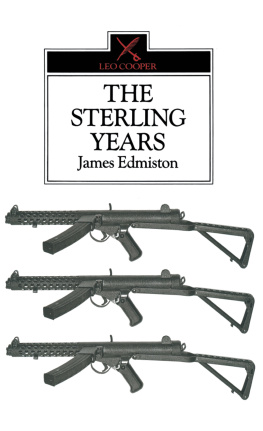

THE STERLING YEARS

THE

STERLING YEARS

____________________________________

Small-arms and the men

____________________________________

by

James Edmiston

LEO COOPER

LONDON

First published in Great Britain in 1992 by

LEO COOPER

190 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JL

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd.,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorks S70 2AS

Copyright James Edmiston, 1992

ISBN 085052 343 5

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Typeset by Yorkshire Web, Barnsley, South Yorkshire

in Times Roman 10 point

Printed in Great Britain by

Redwood Press Limited

Melksham, Wiltshire

This book is dedicated to the staff and workforce of the Sterling Armament Company Ltd, of whose loyalty I have yet to find the equal, and also to those countries who had the good sense to adopt the Sterling sub-machine gun.

CONTENTS

This is a cautionary tale of one mans experiences in the small-arms industry mine. It is the story of how I acquired and subsequently lost the Sterling Armament Company, at considerable personal and financial cost, thanks to the dishonesty, jealousy and hypocrisy of others. It is an explanation of how I came to believe, as I now do, that the day of the truly private military arms manufacturer is over, even in America.

The arms trade is an emotive subject, and small-arms especially so. The gun-worshipper who opens this book with eager hands will find no songs of praise from me. I am proud to have been associated with the manufacture of probably the most reliable automatic firearm ever made, the Sterling sub-machine gun, but this does not mean that I find anything intrinsically glamorous about guns. As pieces of fine engineering they do possess an aesthetic appeal, at least to those who can appreciate such skills, yet the essential fascination derives from their potency as weapons. Whether or not it is true that the assassins bullet has ever altered the course of history, there remains the possibility that it might.

Still less glamorous is the actual trading aspect. The scenery might be exotic and beautiful, the sums of money involved might be huge, but the traders or fixers have to keep a very clear head when dealing with buyers. The risks are high. Double-dealing and corruption may lurk in wait, even behind the most charming and dependable facade even, alas, within the British Government.

It is not my intention however, to point out governmental incompetence, or to underline the waste of money and effort involved on a national level, or to suggest that British hypocrisy over procurement practices is any worse than in other countries. It is merely my wish, in writing this book, to set the record straight for The Sterling Years.

My first experience of shooting was with a .22 Martini rifle in the air-raid shelter that housed a rifle range, down by the River Cherwell. I was 11 years old and at the Dragon School, Oxford. There was a real attraction to me, then, of carrying a firearm and having the trappings of a soldier. Sadly, the practice was stopped not out of any fear for security, but rather because one of the young lads managed to sneak out a live round and then despatched an unfortunate mallard.

After the Dragon School I went to Rugby School in Warwickshire. My father had been a rugby player of some renown, and it was because the game had originated at the school that he chose to send me there. Though I never matched my fathers standard, I enjoyed rugby. I did not like cricket, though, and so during the summers, in order to avoid it, I followed my fathers advice and took up shooting. Now it was a Lee Enfield .303 that I strapped to my back for the cycle ride through town to the Brownsover ranges, today part of a housing estate.

I considered myself quite a good shot, but somehow lacked the right temperament. Sheer excitement sometimes made me ruin my own chances. In a match, when everything hung on the last shot, my unsteady breathing or simple lack of concentration would make me spoil things with a magpie, a wild shot. Still, I did join the clutch of likely candidates for the shooting VIII one summer for the warm-up week at Bisley, and so experienced the delights of the Mecca of the shooting world. The heady moment soon passed. Perhaps it was the sun that sapped my concentration, but Regimental Sergeant-Major Bates despaired of my shooting and I was out of the team.

Meanwhile, however, I had discovered a new dodge. In the swimming matches against other schools there was always a diving event that carried an inordinate number of points towards the match. It had occurred to me that jumping around on a trampolene or a spring-board was a hell of a sight easier than flogging down to Brownsover with a heavy rifle on my back. Therefore I now changed over to swimming or, more correctly, diving. Im almost ashamed to admit it, but I was in the school swimming VIII for two years without swimming a stroke.

Whilst at school we all had to join a voluntary combined cadet force, affiliated to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. On occasions we were sent on exercise and issued with rifles and a few blank rounds of ammunition. The local stationers must have made a fortune, since half the school was firing pencils around the Warwickshire countryside. But there was a considerable gap before I touched a gun again. I now spent an idyllic (and idle) three years at Oxford reading law at Brasenose College, as it happens, where William Webb Ellis had gone before. It was Ellis who, with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time, picked up and ran with the ball during a schoolboy match at Rugby and so invented the game. There are no records as to his further participation in either rugby or association football, but when he went on to Oxford he won a blue for playing cricket for the University against Cambridge.

During my time at Brasenose I played rugby on three occasions against a team from the Honourable Artillery Company. This most individualistic organization was (and still is) a territorial army unit situated on the northern borders of the City of London. Founded in 1537, it is technically the oldest regiment in the British Army. It had fought as a unit in the South African and First World Wars, as an old friend of my fathers recalled while lunching with me at Armoury House, the Regimental Headquarters. During the Great War he had seen HAC batteries bringing their horse-drawn artillery into position and then saw them being picked off, one by one, by the German artillery. The losses were appalling. In the Second World War the regiment became officer-producing. In fact, some would have me believe that it still is.

Having gone down from Oxford I went one day to watch Brasenose play the HAC on their most valuable ground in the City. Apparently it had been a burial ground for victims of the Great Plague in 1665, and the rugby team spread the rumour that anyone who suffered so much as a graze would require an immediate tetanus jab. Some of the HAC players recognized me from past games and were most welcoming. Thereafter I received frequent invitations to dine at Armoury House until eventually, feeling myself under something of an obligation, I picked up my boots again to play rugby for the HAC team.

In fact I ended up joining the Territorial Army. My decision to do so was only partly influenced by the fact that, if I was playing rugby for the regiment whilst technically attending a military week-end, I was paid full army pay as a private or, in my case, a gunner. That was the nearest I came to playing professional sport.