Acknowledgments

I must begin by thanking my editor Kathleen Fleury. Her out-of-the-box thinking, tenaciousness, and tender balance of flattery and tough talk made this book a realityand its author a slightly better person.

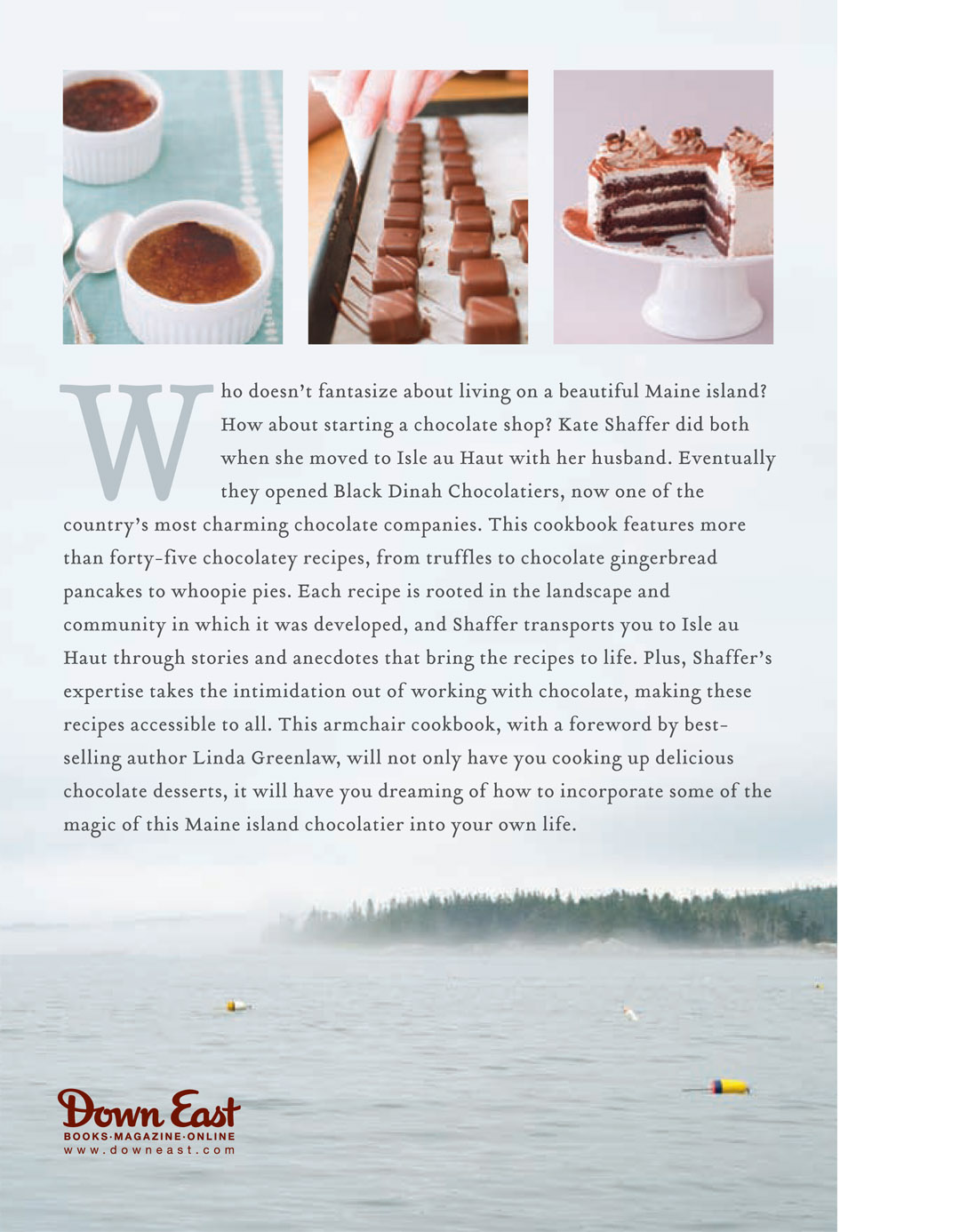

Stacey Cramp is a truly gifted photographer who sees the beauty in the everyday mess of a working kitchen. And then turns it into art.

Warm thanks to Linda Greenlaw, whose friendship and advice helped me to believe that publishing a book is totally worth the hard work of writing it.

My heartfelt gratitude to Lisa Turner, who continues to learn me that its not just about feeding people; but feeding them what they love.

Thank you, Terri Patchen, for spending 8 hours copy editing on the very first day of your vacation on the island.

And a thousand times a thousand thanks to Dianna Dewitt, Alison Richardson, Abigail Hiltz, Sarai Johnson, Bil and Brenda Clark, Diana Santospago, Jeff and Judi Burke, Kathie Fiveash, Albert Gordon, and Nancy and Bill Calvert for their love and friendship and supportand good wineall of which are necessary for a winter of writing and editing.

No one person has contributed more to this book than the collective community of Isle au Hautthose friends and neighbors who have taught me that a place is only made perfect by all of its imperfections.

Chocolate 101

CHOOSING YOUR CHOCOLATE

When Steve and I got the notion to go into the chocolate business, we knew pretty much zilch about it. All I knew was that if we were going into the chocolate business, then we needed chocolate. So, while Steve was doing the hard work of creating a business model from twigs and island spruce needles, I hopped the morning mailboat and went shopping.

I had a working knowledge of modern chocolate terminology, so when I found myself on the mainland in front of the chocolate counter at my favorite gourmet food store, I had a pretty good idea of what I was looking for. Not that it mattered. I was a woman on a mission, and my mission was to discover the very best chocolate with which to make my truffles. So, I bought every bar in front of me. Oh, and a cup of coffee. And a bottle of wine. The cashier didnt bother with discretion. Bad day? she asked.

Since Steve and I werent making chocolate solely for ourselves, we felt that it would be important to get some other input besides our own. On a quiet mid-winter night, when there was nothing to do on the island but wonder what our neighbors were up to and who they were up to it with, we instead held an informal chocolate tasting. A group that consisted of a handful of lobstermen and carpenters, a boat builder, the school teacher, tax collector, innkeeper, park ranger, lighthouse keeper, and a selectman reported to our small living room for duty, received a brief explanation on how to approach their task, and then got down to work. It was a fairly structured blind tasting; which basically means that I unwrapped all the bars I had bought earlier in the day, laid them out on a numbered grid scribbled onto a large piece of butcher paper, and then handed each taster a sheet that had a table of attributes I wanted them to pay attention to.

After the dust settled, there was a clear winner. And I really, really wish I could tell you that the chocolate that won the taste test that night was the chocolate we ended up ultimately using in our truffles. But its not. There are, unfortunately, other factors we needed to consider, such as cost and availability, which quickly disqualified several of the chocolates we tried. Instead, second place received the honors, and it ended up being the right choice all around.

So, what does this all mean for you and how you choose the chocolate you use for the recipes in this bookand beyond?

For the most part, all of the chocolate work and recipes described in this book can be done with a quality chocolate youd probably be able to find on the shelf of your local grocery store. Even our grocery store, which consists of three twelve-foot aisles, is open for two hours, three days a week, and caters to an off-season population of forty-five people, carries chocolates suitable for a batch of French-style truffles.

However, it might help if you make a list of criteriawhat you want and dont want in your chocolatebefore you start purchasing bars for your tasting. Here are some possible questions to ask yourself:

Is it important that your chocolate be fair trade?

What about organic?

Do you want a single origin chocolate, or is a blend okay?

Whats your price range?

How easily can you get it? And how quickly?

These days, buying a bar of chocolate can be as intimidating as buying a bottle of wine. To this, I say, Whatever. Heres the deal: if it tastes good, it is good. And by that I mean that Ive found that Vianne Rocher (the beautiful chocolateur in the luscious movie Chocolat) was right: everyone really does have a favorite, and it rarely has anything to do with how much it costs, how shiny the label is, and whether or not it has a French name. Most of us, if were breathing, have been eating chocolate since we were babies. We learned to like it before we knew how to explain why we liked it, or what exactly we liked about it. I call this the Zen mind of chocolate. We dont have to learn, as with wine, what we like and dont like. We already have a developed palate with chocolate; we already know what we like.

WHAT EXACTLY IS CHOCOLATE?

Chocolate comes from the seeds of a cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, native to tropical regions of the Americas and cultivatable in regions between zero and twenty degrees latitude, north or south of the equator.

Modern chocolate making is basically a six-step process, which is still, surprisingly, much like how it all began.

STEP 1: HARVEST AND SEED EXTRACTION

The fruit of the cacao tree are ridged football-shaped pods that vary in color from green to yellow/orange and red. They grow directly out of the trunk of the tree and are harvested by hand by knocking them off the trunk with a stick or by cutting them off with a machete. The pods are then split lengthwise (again, usually with a machete) to expose a mass of almond-size seeds encased in a sticky white mucilage.

STEP 2: FERMENTATION

Next, the seeds (or beans, as they are more commonly called) are scooped out of the pod and heaped in a pile or into wooden crates to ferment. The heat created by fermentation helps to melt off the gooey white stuff, so that all is left is the seed. The heat also kills the germination process and is key to beginning to develop the full flavor of the seed. This process takes anywhere between three and nine days.

STEP 3: DRYING

After fermenting, the beans are spread onto rackseither freestanding racks or roof-mounted onesor tossed out onto roads or whatever flat surface is available in great quantities, and allowed to dry in the sun. Drying takes from seven to thirty days.

STEP 4: ROASTING

After drying, the beans are ready to roast. Some producers choose to age their beans for a quantity of time before roasting. The benefit of aging is primarily flavor development, and those who employ this practice feel that it is key to the quality of their final product. But whether or not the producer chooses to age their beans or not, roasting is where the true art of chocolate production takes flight.