Veggiestan, or land of the vegetables there is, of course, no such word, and no such country, but to my mind the Middle East more than merits the name. The regions constituent nations are simmering, bubbling and bursting with sumptuous vegetarian traditions and recipes.

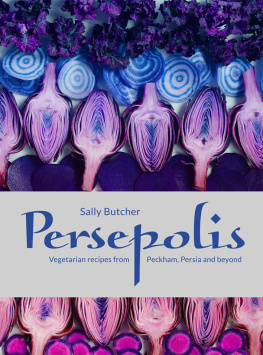

When I was writing my previous book, Persia in Peckham, the temptation to stray and explore other parts of the Middle East was pretty compelling. You see, I am an omnivore, but I dont like meat very much. In fact, I have a better relationship with vegetables than I do with a lot of people. This book is born of that passion.

It is also born of an awareness that our markets and delis are filling up with strange-but-delightful foods that we often avoid and sometimes scare us. Alien squash, sour cherries, okra, taro, any number of strange herbs and spices. This is the stuff that goes into the dishes that feed our changing population. And Im not just talking changing demographics; the indigenous population is shifting towards a more enlightened and healthier diet.

Even vegetables that we thought we knew pretty well Mr. Bean, Mrs. Turnip, Miss Beetroot will, with a twist of Middle Eastern expertise, change before our very eyes, like a neighbour finding her naughty, inner floozy. OK, so weve all tried ratatouille and moussaka, but the aubergine (and its sidekick the courgette) is bursting with more potential than a Pop Idol finalist; pumpkin is far too much fun to be the preserve of October ghouls; and most of us have little knowledge of other squashes.

Fragrant spices, aromatic herbs, pulses and grains beckon. When I was knee-high to a soya bean, being a vegetarian meant nut roast and always having to say youre sorry. But in the capable hands of a Middle Eastern cook, stalwarts such as the trusty but much maligned lentil reach new pinnacles of tastebud titillation. Or what about pot barley: slow-cooked, risotto-style, dotted with fresh coriander, crunchy pine nuts, saffrony raisins? This is not the same humble grain that we bury in soups, surely?

I would like to think that, armed with this tome, you will be able boldly go to the aisles and shops that you have never been to before and seek out new vegetables, weird ingredients and strange fruits. And cook them.

What have I personally discovered? I already knew that humous was not the only career option for a self-respecting chickpea. And I already had a few winning Persian ways with vegetables in my repertoire. But I have learned what a sensible, backseat place meat occupies in Middle Eastern cuisine: it is not the main event, but rather a luxury, and in many cases an optional extra.

VEGETABLES IN THE MIDDLE EAST

I have begun to embrace simplicity. Vegetables in the West have had to endure centuries of over-complication and, in the case of British cooking at least, over-cooking. The day that my Iranian mother-in-law took me to task over broccoli stems remains stuck in my mind: I was about to lob them in the bin, as you do, when she pointed out that I was actually jettisoning the best bits. She peeled the broccoli so that the white core was revealed, sprinkled it with some salt, and offered it to me to, um, prove her point.

My first time with fouls medammas was similarly revelatory. A bitterly cold Ramadan day a number of years ago saw us trying to assemble a pallet of pickles in a windswept cul-de-sac somewhere exotic like Hayes. The shopkeeper to whom we were delivering was a man of few words and little inclination to pay, but he had the natural courtesy of the Arab nations, and as his staff were about to break fast, he indicated that we should join them. Upturned olive tins became improvised seats, and out came sweet tea, dates, bread, cheese and a huge vat of unprepossessing sludgy brown beans. No sauce, no nothing. Just a pot of salt and some lemon wedges by way of accompaniment. A nervous first prod with a broken plastic spoon took me straight to bean heaven. Me and fava beans have been intimate ever since.

You see, Middle Easterners seem to have a clearer idea of what is best for a vegetable, and the tastiest way to prepare it whilst retaining its innate goodness.

NEW FOODS BROUGHT BY TRADERS

The climate of the fertile crescent and the -istans stretching across towards India is famously suited to the cultivation of just about anything, even when the terrain is unfriendly. The position of Mesopotamia (now mostly Iraq) as the cradle of civilisation, and the fact that the region is at the crossroads of the routes of a myriad traders between the East and West, has meant that the Middle East has always been in the middle of stuff, perfectly placed to grasp new foods, methods and cultural elements from passers-through. So ingredients there are aplenty.

This mingling of traders and blurring of borders has meant that, in terms of food, it is at times irrelevant to differentiate between some of the Arabic nations. Many of the recipes I have featured are for generic Middle Eastern dishes, the precise origins of which have long been buried in the shifting sands that comprise the region.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE MIDDLE EAST

The Middle East is a something of a geographic amoeba, shape-shifting with the tides of history and indeed in the eye of the beholder. Does it include Turkey, which is also part of Europe? What to do about Morocco, which is mostly populated by Arabs, but is no more easterly than Doncaster?

The Iranians use the loose term Arabistan to denote any of the Arab countries; its a nice word and one that I will happily use here (although in truth many of the countries involved still distinguish between the Arab-settler population and the indigenous tribes). The term Arab referred historically to the peoples of the Arabian peninsula and parts of Syria: Islam came along and spread the culture (and the word of Allah) across Northern Africa and other receptive bits of the Near East. The Indo-Iranian tribes, which ranged from India through to Kurdistan, and Turkic-speaking people, from Turkey through Azerbaijan to Uzbekistan, had strong cultural identities of their own, and so although most of them embraced Islam, they resisted total conquest and retained their own languages and social structures. This means that you shouldnt call them Arabs, or they will be upset.

Regardless of their origins, Middle Eastern people are generally in touch with their roots (the worst clichs are often used in the culinary sphere), and so the real properties of food, its medicinal values and foodie anecdotes are kept alive around the dinner table and passed from mother to daughter. Middle Easterners live their food: it is part of their day-to-day existence, not a function of it. And the family meal is non-negotiable. As such, it is a pleasurable and relatively easy task to capture the region on paper.

A VEG-SPECTIVE

OK, so I am not a card-carrying, full-time vegetarian. I have a terrible weakness for chorizo. And I eat my (very occasional) steaks blue. But I truly prefer vegetables. And I am not alone; there are hordes of new (part-time) vegetarians out there.