Introduction

The person who constantly eats vegetables can do everything

Chinese proverb

With hindsight I now realise how fortunate I was to have spent my childhood and early teens in that part of the world we call the Fertile Crescent or the Middle East. Fortunate, not so much for the educational and material advantages, but for the simple, peaceful (then), almost biblical way of life. I was brought up in two major towns Aleppo and Beirut, where the pace of life was as calm and assured as that of a camel. Indeed, both towns belonged to the camel, the sheep, the goat not forgetting the mule and the ox. Throughout there existed a natural harmony which, alas, was abruptly shattered when I set foot in Britain one rainy, foggy August day. That was well over 30 years ago and by now I have become acclimatised to all the vagaries of Nature except one the limitations of her fruit and vegetable products. I admit I was spoilt.

Our house in Beirut was an island surrounded by apple, orange, cherry, chestnut, tangerine, palm and banana trees. We hardly ever bought any oranges, but simply picked them from the trees. Occasionally we bought a 22 kg (50 lb) sack of the famed Antilias oranges (better known in Britain as Jaffas) from neighbouring orchards for a few pence. My family went through at least two such sacks a week and no-one blinked an eye. Imagine my consternation when, upon our arrival at our new home in Manchester, we (my younger brother and I) found no sackful of oranges in the kitchen. There was nothing but potatoes, onions, cabbages and leeks. These were not unknown to me, but who in their right mind could go on eating potatoes day after day when such vegetables as aubergines, okra, courgettes, kohlrabi, spinach and peppers were the everyday vegetables of his old country?

Since food plays a major role in the life of a Middle Easterner, my life suddenly became dull and unappetising.

My mother, excellent cook that she was, tried to enliven our beleaguered diet with all kinds of innovations and substitutions. Relations and family friends from Paris, Aleppo, Beirut and Cyprus would send us Christmas packages filled with dried fruits, vegetables such as green peppers, courgettes and okra, apricot paste (amardin), goats cheese, sumac powder, herbs and spices to alleviate the siege mentality that had enveloped our very souls.

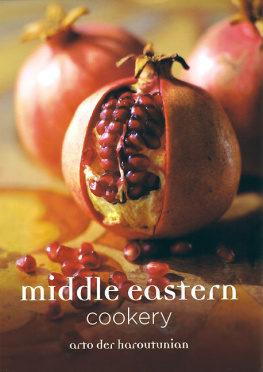

I recall (much to my chagrin and amusement) how, during those early years, I went to sleep in tears, longing for the fresh mulberries and blood-red pomegranates of our Beirut garden. With hindsight, I now realise how fortunate I was to have spent the formative years of my life in the part of the world that was the orchard of our Western civilisation. For, from a very early age, I ate, enjoyed and appreciated many of Natures wonderful products unconsciously.

Today in Britain, however, all the variety of Nature is ours for the buying. At the local Indian grocery a box full of sweet potatoes from the West Indies is flanked by chayotes and pawpaws from Brazil; silky smooth aubergines from Kenya or Spain or Israel are shelved next to twisted karelas (bitter gourds) and there are other gourds of different shapes and sizes, some weighing up to 22 kg (50 lb). There are boxes of pickling cucumbers from Holland, tindoras (tiny cucumber-shaped vegetables not much larger than radishes) from Bangladesh, Far Eastern white radishes, courgettes from Italy, yams from Africa and kohlrabi, beets and spinach from Greece. Then there are the chillies small, bitter, hot, pungent, large, green or red from all parts of the globe; and those delicious fruits: guavas, mangoes, pineapples, grapes, fresh dates, watermelons the list could go on and on which have made me, belatedly, realise how fortunate I am to be living where I do. Indeed, I can most assuredly affirm that no other part of the world has such a wealth of choice. The reasons are obvious. Our climate, with its shortcomings, has forced us to import extensively, thus the world has become our oyster. The immigrants, too, have brought with them the foods that sustained them at home and these are now becoming commonplace on oursupermarket shelves.

LEARNING ABOUT NEW VEGETABLES

But what do you do with it? My local Indian greengrocer smiles a sad butunderstanding smile and goes on to explain most patiently how to prepare thedrumstick I am pointing at. Its very tasty, he says, his eyes gleaming under the neonlights, and I know I will not be disappointed.

To all my questions he or his assistant, and several times his wife, who comes rushingout from her kitchen, give precise details of the many ways they have been cookingthis or that unknown vegetable for centuries in their part of the world.

I understand that longing in their eyes or on the edges of their lips as they expoundthe diverse qualities of the vegetable under discussion; a few years ago I, too, wouldlovingly describe to my classmates, as we played in the school yard, what a palm tree,a banana or a watermelon looked and tasted like and would feel a pang of longing forthe sun-drenched orchards of my childhood.

This book is about vegetables: the known, the little known and the few still unknownto the British. This is also a vegetarian book. In essence it is an excuse on my part toexalt the many qualities in vegetables. It is vegetarian because vegetables are at theirbest when treated as they are without the addition of meat, fish or poultry.

The recipes in this collection hail from every corner of the world and are classics intheir own right. Some will undoubtedly be known to you, others are still confined totheir native regions. I have not adapted any recipe to rechristen it as vegetarian.Hence several well-loved dishes have consciously been omitted because they mayhave included rice or other grains, or pastas, or rashers of bacon. What is left is a rich,wholesome repertoire of fascinating recipes reflecting mans tireless drive to createfood that flatters his palate, fills his stomach and satisfies his bodily needs.