Many thanks are due to all the authors, translators and publishers from whose works

I have quoted, and apologies to those who unintentionally may

have been overlooked.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

If Choregs (dry breads) were good enough for our ancestor Noah, they are good enough for us mere mortals on the barren hills of ours, waiting for night to become day, snow to melt, howling winds to disperse, the return of the holy sun and the resurrection of our Lord; so we can celebrate with the honey of wild roses, the fruit of the trees, milk of our sheep, the fragrance of spring air and huge, huge mouthwatering trays of Bahki-halva (Baklawa). Praised be the Lord. Praised be the dry bread of our ancestors.

Armenian Wisdom

There is a charming Armenian legend about how old Mrs Noah, when informed by her husband of their impending cruise to the unknown, rushed home, gathered her daughters and daughters-in-law around and hurriedly prepared vast quantities of choregs (small dry breads that keep for months); for who could tell how long the journey would take? I have always found this brief glimpse into our ancestral past utterly delightful in its cosy domesticity; with women of all ages pouring large jugs of water on to coarse flour in earthenware containers, kneading, rolling the dough, some shaping with their delicate fingers the patterned bread, others baking the bread in a small oven in one corner of an old house with old Mrs Noah supervising the proceedings. I can smell the sweet aroma of bread mingled with perspiration, the fresh desert air with the odour of sheep and mules. I can sense the fear and excitement of the forthcoming journey, while Noah and his sons busied themselves in the courtyard putting the finishing touches to their boat.

All this from a legend passed down through the ages from mother to daughter, from my grandmother to my mother. It will also have passed to the mothers of many other Middle Eastern people mostly unknown to me, some related, many friends or friends of friends, without whose tenacious conservatism, deep-rooted traditionalism and undoubted love of food these recipes could not have survived. For one of the most interesting points to be discerned from the legend of Noahs wife and her choregs is the strength of traditionalism in the Middle East where the cuisine (to date) is basically unchanged from time immemorial. The next point is that the source whence most Middle Eastern food is derived is in the shared ancestry of the people whatever their nationality, tongue or habitat today.

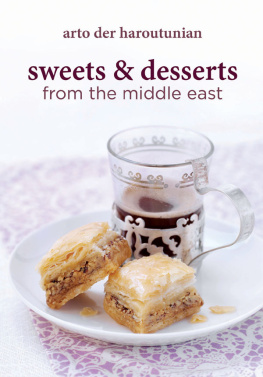

In this book I have gathered a selection of Middle Eastern desserts and sweets (by no means a comprehensive collection since the actual list would run into thousands). I have reluctantly omitted certain recipes which would not only be time-consuming, but also impracticable to create due mainly to the lack of necessary ingredients in the West. I have also tried to keep true to the spirit of the dishes and have not attempted to improve or improvise for the sake of convenience one should only adapt out of sheer necessity and not for its own sake.

The little that is known in Europe and America of Middle Eastern sweets is dismally lacking in finesse and abominably false in representation. This is due in part to the commercialism of most Middle Eastern restaurants and delicatessens. Only a handful of famed specialities such as baklava, kunafeh (kadayifi), galatabourego and rahat lokum (Turkish delight) are known. I hope this book will help to lift the silky veil of ignorance through which the Middle East is often viewed by westerners. Gone are the days of camel caravans carrying spices and exotic carpets from one end of the desert to the other. Gone are the days when the langorous nymphs of the harems joined days into nights by munching Turkish delight, splitting passotame (toasted pumpkin seeds) and drinking ice cool sweet sherbets. Today the entire Middle East has woken to the realities of our age and the people of the deserts, with those of the hills, are striving to catch up with the industrialised West not only materially, but also (each in his own way) socially by updating his moral and political concepts in tune to this technological age of ours.

Very little is known of the food of our ancestors. A few hieroglyphic recipes from Egypt, Sumer and Urartu, where beer, wine, many types of bread and honey-based sweets were known, have come down to us. When Rome conquered and subjugated vast areas of the known world of her day she also created the first international cuisine where Pumpkin Alexandrine-style (Aliter cucurbitas more Alexandrino) was often served with Parthian chicken (Pullum Parthicum) and Cilician bread. The Roman cuisine was in turn equally influenced by her conquered territories. Apicius, in his de re coquinaria (a compendium of dishes from all over the then known world) notes several dishes of his day which are still (almost intact) prepared in the Middle East. One such recipe is Dulcia domestica et melcae, a confection of dates which, after the stones have been removed, are filled with nuts, sprinkled with salt and candied in honey similar to the stuffed date recipes of Iraq and the Gulf States.

The second and most influential style of cooking was that of the Arabs who spread via Arabia in the 7th century and in a short time dominated the entire Middle East barring Byzantium and certain mountain regions of the Caucasus. The Arab cuisine at this early stage in history was limited and poor, for the desert could not offer much. The social structure of the Tent people was equally primitive, while in Byzantium and to a lesser extent in Persia there had been large cities with a sophisticated urban population. The desert only had nomads without roots or a sense of belonging. However, it did not take long for these Arabs to settle down in the green valleys and pastures of the Mediterranean coastline. They absorbed all the social infrastrucrure of the natives, who were Christian Syrians and Assyrians as well as Copts, Persians and Greeks. Thus in the matter of a few centuries not only was Arabic the dominant language in the East, but also the religion and social make-up was that of the Muslims. All food acquired an Arabised name and what was once perhaps an Assyrian speciality from northern Iraq soon spread to all corners of the Muslim Arab empire. Thus the popular sweet named ghorayebah (lovers pastry) so called because of its traditional heart shape, which was most probably of north Syrian origin, appears in name and basic content today as far away as Morocco, Tunisia and southern Iran. Another example is baklava which is mentioned in Armenian folklore of the 10th-12th centuries, spread throughout the Arab world and later on further still to the Balkans during the Ottoman rule.