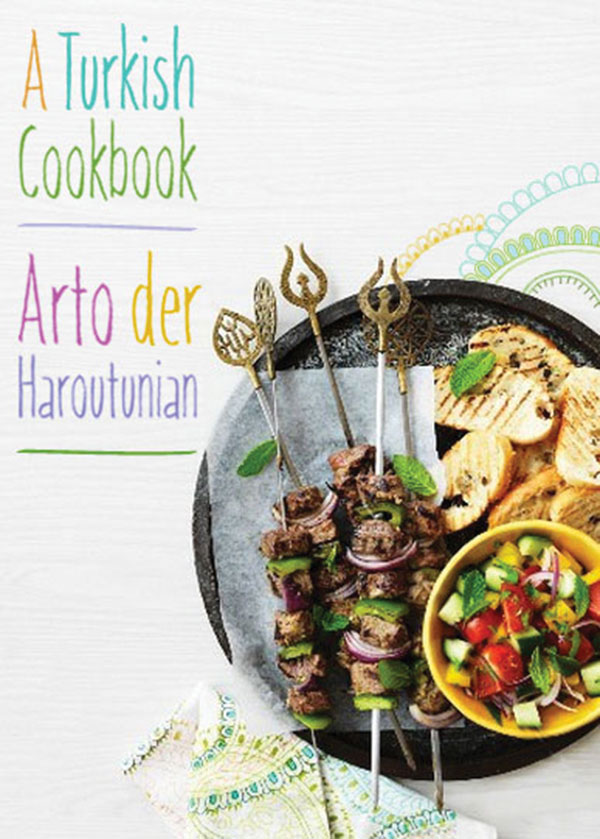

a turkish cookbook

other books by arto der haroutunian

classic vegetarian cookery

vegetarian dishes from the middle east

middle eastern cookery

north african cookery

the yogurt cookbook

sweets & desserts from the middle east

a turkish cookbook

arto der haroutunian

GRUB STREET | LONDON

NOTE

All recipes serve 6 people unless otherwise stated.

The ingredients given in this book are in both metric and imperial measures. Use either one or the other as they

are not interchangeable.

Published by Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London SW11 6SS

Email:

Web: www.grubstreet.co.uk

Twitter: @grub_street

Facebook: Grub Street Publishing

Text copyrightArto der Haroutunian 1987, 2015

Copyright this edition Grub Street 2015

First published by Ebury Press in 1987

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-909808-24-9

eISBN 978-1-909808-24-9

Mobi ISBN 978-1-909808-24-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permissionof the Publisher.

Artwork: Roy Platten.

contents

introduction

I am a Turk; my faith and my race are mighty.

MEHMET EMIN (POET)

On 21 October, 1923, with a salute of 101 guns which thundered across the skies, the Turkish Republic was born amidst wars, plagues, massacres and fratricide. The Caesarean birth killed the mother the Ottoman Empire while the child saw the light of day helpless and kinless. Decades later, Turkey still stands alone, surrounded by historic enemies and unsure of her position in the family of nations.

The name Turkey has been used (by the Europeans) for Turkish-speaking Anatolia almost since its conquest by the Seljuks in the eleventh century, though the history of the country is astoundingly long almost 10,000 years and the earliest inhabitants have been traced back to 7500 B.C. Hittites, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians and Romans all swept through the area and established their civilisations here. In the imperial society of the Ottomans the ethnic term Turk was little used and then chiefly in a rather derogatory sense, to designate the Turkoman nomads or later the ignorant and uncouth Turkish-speaking peasants of the Anatolian villages. To apply it to an Ottoman gentleman of Constantinople would have been an insult.

The Turks originated in Central Asia, Siberia and the great northern plains on either side of the Ural Mountains. According to legend, Turks came from the mythical land of Turan where they lived in wealth and splendour. A great leader called Feridun divided his lands between his two sons, giving Iran to Ir and Turan to Tur. People who now call themselves Turks were better known to the Chinese as Tu-kin. They came from the eastern frontiers of the Islamic Califate in Central Asia and penetrated the Arab-ruled lands as slaves and mercenaries fighting for Islam. There were hundreds of Turkic-Mongolian tribes and amongst them were the Oguz, the ancestors of the Turks of Turkey.

In the year 1071, near Manzikert (Manazgird) in Armenia, the Turkic-Mongolian tribes, under the leadership of Alp-Arslan, clashed with the forces of Byzantium. The Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (Romanus Diogenes) was defeated, and the gates of Asia Minor were opened to the nomadic tribes from Central Asia. The Turkic invasion of Anatolia in the eleventh century, and the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in the fifteenth, brought to completion the assault of Islam on the eastern Roman Empire initiated by the Arabs in the seventh century.

In the ensuing 850 years those Turkic tribes created and lost a vast empire, based on religion, that in its heyday stretched from the shores of the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean and from the gates of Vienna down to the Red Sea. The Turkish people were saved from eventual oblivion, and no doubt assimilation, by the vision, courage and determination of a great leader, Kemal Atatrk, who by sheer force of character pulled his people from the brink of disaster and literally forced them to enter the twentieth century.

Atatrk created some say invented modern Turkey, but the people who first began to change the fabric of a well-established Christian society based on two ancient lineages that of the Greeks of Asia Minor and the Armenians were those of the Oguz tribes from the family of Seljuk. The Seljuks were the first Turkic people to settle and establish roots in Asia Minor, with their capital in Konya (ancient Konium) in the heart of Anatolia. Their rule lasted until the beginning of the fourteenth century and was known as the Sultanate of Rum.

In 1243, near Kse Dg in Eastern Turkey, the army of the Sultan of Rum was defeated and the hordes of Mongol-Khans plundered their way throughout Asia Minor. The Mongols who destroyed the Seljuk Empire, as well as the Shahs of Persia and the Califs of Baghdad, were too weak to govern the lands they had ravaged. They abandoned the western districts of their empire to the Turkoman lords who, in turn, established the states of Ak Koyunlu, Kara Koyunlu and Ramazan Olu. These Turkoman dynasties were later to be vanquished by the Ottoman ruler Muhammed II the Conqueror in the late fifteenth century. The Ottomans, a dynasty founded by Osman (from whose name derives the word Ottoman) at the beginning of the fourteenth century, established themselves along the shores of the Sea of Marmara and on the Aegean, where they were engaged by land and sea in the Holy War of Islam against the Christian infidels. The Byzantine Empire was finally conquered with the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

In spite of earlier setbacks at the hands of Timur (Tamerlane), the Persian conqueror, the supremacy of the Ottomans was consolidated, and in the reign of Selim I (151221), the Ottoman conquest of Asia Minor, Northern Persia and all the Middle Eastern territories of Syria, Egypt, Armenia and Kurdistan was completed. It was left to the sultans who followed Selim, from Suleiman I through to Mahmud II (180339), to hold most of these lands, but already by the middle of the eighteenth century the Empire had passed its peak.

The Ottomans were not interested in trade as a profession very much like the ruling aristocracies in England and France of the day. They were born to function as administrators, soldiers or to work on the land. Trade was in the hands of Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Lebanese. Much of the overland trade from Persia and the East in Turkey as in Russia was Armenian; there were Armenian as well as Jewish colonies in Leghorn and Marseilles. Greek ship owners ... already dominated the Black Sea. Furthermore, the very institutions that had contributed to the strength of Ottoman power also carried within themselves the seeds of their own destruction. The centralisation of power made for efficiency as long as those powers were in strong hands, but they also provided rivalries between the numerous offspring of the Sultans. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, despite various attempts to endow the Empire with modern structures army, law, institutions, transport, education and so on the final agony of decline inexorably set in. Romanians, Bulgarians, Serbians and Greeks liberated themselves, while the Big Powers Austria, Russia, France and England quarrelled like hungry vultures in anticipation over the spoils of the Ottoman Empire which, as yet, had not completely been brought to its knees. All attempts at reform failed mainly due to corruption prevailing inside the Court.

Next page