Copyright 2011 by Jacques Ppin

Illustrations copyright 2011 by Jacques Ppin

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Book design by George Restrepo and Lisa Diercks

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover version as follows:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ppin, Jacques.

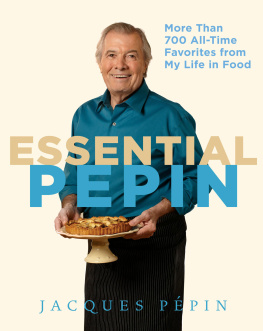

Essential pepin : more than 700 all-time favorites from my life in food / Jacques Ppin.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-23279-9 (hardback)

1. Cooking, French. 2. Cooking. 3. Cookbooks.

I. Title.

TX719.P4578 2011

641.5944dc23

2011016057

Enhanced ebook ISBN 978-0-547-60738-2

v4.0315

Acknowledgments

The making of a book is a complicated project, with many people involved in writing, editing, and designing. This book of many books was particularly complicated and goes back many years. I have always counted on my wife, Gloria, for food advice and ideas. Norma Galehouse, my longtime assistant, has worked on this book in various ways for the last twenty-five years, and I continue to rely on her patience and talent to make something readable out of my handwriting and notes. Thank you to Doe Coover, my agent, who came up with the idea for the book, and to Rux Martin, my editor, for her confidence and enthusiasm for the project and her willingness to listen to my grumbling. Thank you, too, to the copy editor, Judith Sutton, for her faithful attention to details; to George Restrepo, for his splendid design; to Jacinta Monniere, for her accurate typing; and to Rebecca Springer, for overseeing the production of the book.

With the book comes videos of techniques filmed at the home of my friend Susie Heller. Her friendship, dedication, and knowledge made it possible. Thank you to my friend and talented director Bruce Franchini; to Paul Swensen, the DVD editor; and to Amy Vogler, David Shalleck, Jean-Claude Szurdak, and the whole technical crew. Your hard work and professionalism made me look good. Merci!

After nearly twenty-five years of working at KQED, I feel I am coming home when I get to Mariposa Street in San Francisco. Although its not possible to thank everyone at the station who has worked on my shows, I want to thank John Boland, the president of KQED and my supporter and friend; Michael Isip, the director of KQED and executive producer, for his confidence, enthusiasm, and friendship; and Jacqueline Murray, for raising the money. More than anyone else, I want to thank Tina Salter, my series producer, for her professionalism, insight, patience, humor, and devotion. Thanks, too, to the genial Bruce Franchini, our director, whose keen eyes made the food look incredible; Christine Swett, the culinary producer, for her kindness and talent; Elizabeth Pepin, the competent associate producer, among many others. And thank you to the back kitchen: first, to my dearest friend, Jean-Claude Szurdak, who appeared on the show with me, and to David Shalleck and his crew, including Michael Pleiss, as always.

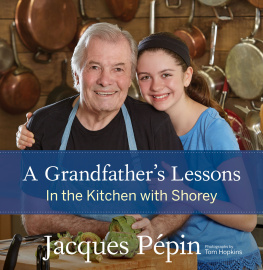

Thank you to my daughter, Claudine, and granddaughter, Shorey, for appearing on the series with me, as well as to Roland Passot, Loretta Keller, and Emily Luchetti. A big thank-you to the operations/technical crew for their efficient, skilled work on my behalf. Last, but importantly, thank you to Wendy Goodfriend, the website genius, whose work I know I do not appreciate enough, because of my limited knowledge of the Internet.

Introduction

In my sixty years as a cookas a professional chef, a husband, a father, a grandfather, an author of many cookbooks, and a cooking teacherI have created thousands of recipes, each memorable and worthy in its own way. Now, for the first time, I have taken stock, reflected back over my life in the kitchen, and assembled the best in one place: the recipes I love the most.

This is a new bookeverything has been rethought and updatedbut it is familiar as well: its like meeting up with an old friend, because it goes back to the beginning of my culinary writing. It is essentially the way I have cooked as a young man, as a mature man, and, now, as an older man. It demonstrates the ways I have changed through my many books, my many moods, my many styles, from elaborate classic French cooking to fast food done my way. It shows how I have changed and learned. Like any working chef, I have always experimented with different foods and different methods. The recipes that I have created through these years are the diary of my life. I am, have been, and always will be a cook: my culinary identity defines me.

When I decided to put this book together, I believed it would be a cinch to do, an easy matter of assembling and reorganizing recipes. It turns out to have been a huge endeavor, bigger by far than writing a cookbook from scratch. Each period of my past exemplifies widely different styles and methods, from the cooking times for fish and vegetables to the amount and types of fat used, to the presentation, as well as procedures and techniques. As a result, I had a real conundrum: either leave the recipes as they were, to represent exactly a moment in time, or adjust, correct, and retest the recipes for a modern kitchen to make them usable, friendly, and current for todays cook while retaining the spirit and flavor of the originals. I chose the second option, with a few reservations. Through all the adjustments, I have tried to keep the intrinsic quality of the recipes as they were conceived. The appetites of a young, a middle-aged, and an older man are different, but a certain continuity remains. In that context, this book represents me more today than at any other time in my life.

The food of my youth in France, during and after World War II, left an enduring mark on my cooking. My mother and aunts thriftiness and creativity with leftovers and incidental ingredients unconsciously became part of my own approach, which, I believe, is one of my greatest assets as a cook. Even during my restaurant apprenticeship in the late 1940s and early 1950s, we were still feeling, to some extent, the burden of privation, and that was reflected in a great respect for ingredients and how they were used.

The 1960s was a decade of change, transformation, and learning. Fresh from France, I was discovering America. For the entire decade, I worked for Howard Johnsons, a chain of more than one thousand hotels and restaurants across the country. With my friend and mentor, Pierre Franey, with whom Id worked at Le Pavillon, Americas signature French restaurant and my first job in this country, I was hired to develop new ideas and recipes. It was a new world of food, where I learned about mass production, the chemistry of food, new technologies, and the American palate. Clam chowder and fried chicken were replacing quiche and coq au vin in my repertoire. I was both expanding on and breaking free of my classical French training, learning that there was more than one way to slice a tomato and that a chicken could be sauted with or without the bones, covered or uncovered, and seasoned before or after sauting. At the same time, paradoxically, I was rediscovering France. I left school at the age of thirteen to go into a restaurant apprenticeship, and although I was an avid reader, I had to wait until my time at Columbia University to meet Molire, Rousseau, and Voltaire and to familiarize myself with the philosophies of Descartes, Sartre, and Camus.

Next page