I dedicate this book to my best friend Christine Topping, without whose patience and care I would never have had time to write this book

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

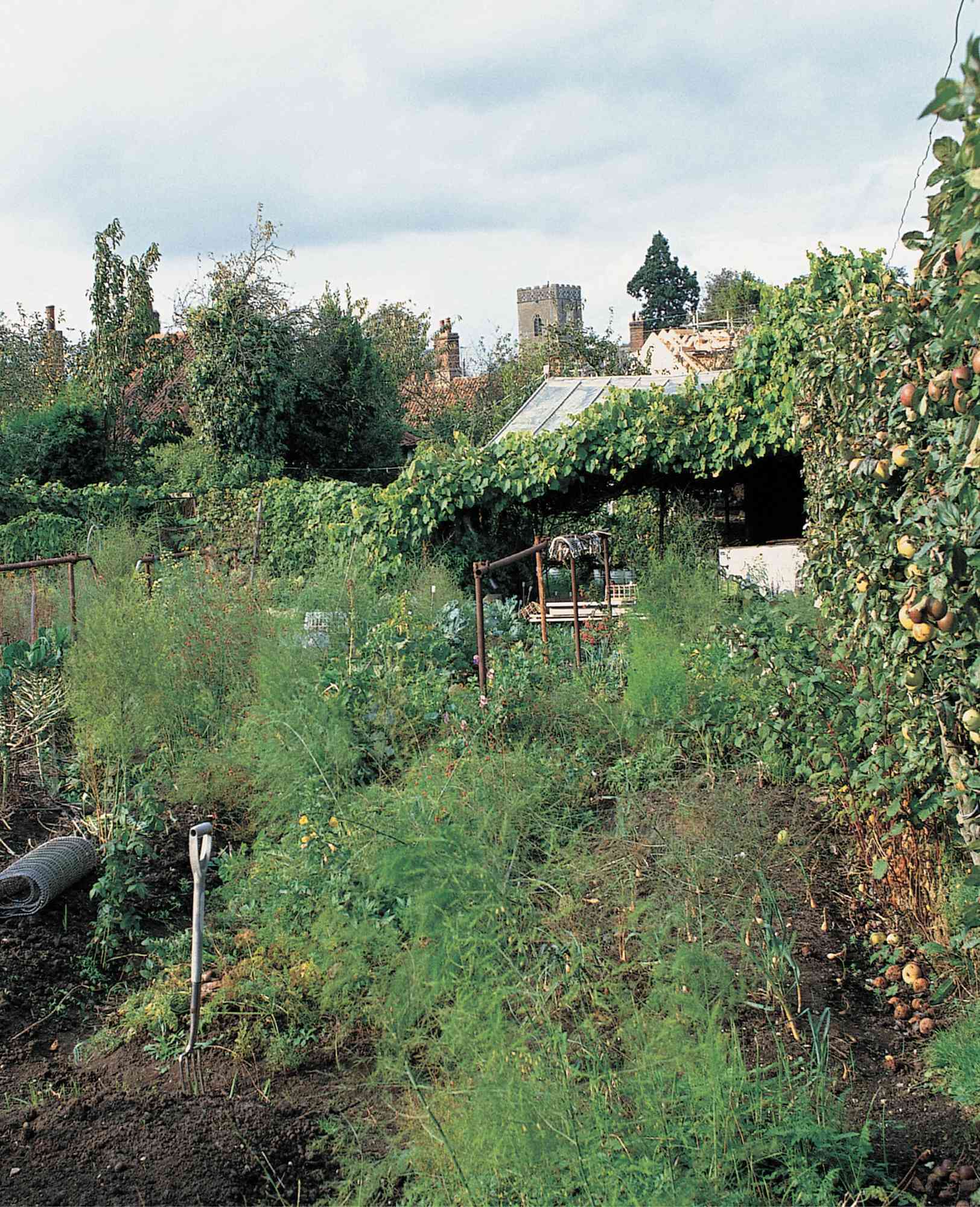

Since the first edition of this book the world has moved on. We are all now aware of the dangers of climate change, the precariousness of our economic position and the continuing threat of wars, famines and fuel shortages. The allotments are full for the first time since the Second World War. Humble dwellings with a large garden are once again desirable, and all the world and their dog want to grow their own organic food.

Yet the talk is always of worthy vegetables; fruit is wrongly considered a luxury, when it is greener, more tasty and less work. We need to get away from the annual, dig, sow, thin, water, feed and weed work ethic and move to a plant, prune and sit-back culture.

Fruit is perennial: you plant it well and it can outlive you. Fruit is less effort. Fruit also locks carbon dioxide into wood, something you try not to achieve with vegetables! And fruit is just so beneficial to wildlife in blossom and habitat, and especially if we fail to protect it.

Indeed, we need to move farming as well as gardening to a more perennial philosophy. Fruit trees should be growing overhead, providing fodder as well as food or even fuel, with other fodder crops growing underneath, getting more from the same land, with fewer energy inputs and with a greater diversity of crops. The world relies on the grasses to provide almost all of our food energy (rice, wheat, maize, barley, oats, sorghum, sugar cane, as well as grazing grass). If, the gods forbid, a disease were to wipe out the grasses we would surely starve. Most of our agriculture is concentrated on these few crops. And almost all meat is grassfed, yet we could feed our animals with fruits and nuts instead. For example, few annual crops rival hazelnuts in fat and protein production.

In our gardens we can start this truly green revolution. If humanity is to survive we need greater, not less, biological diversity. The gardener grows many more crops than the farmer, but still only a few dozen. We need to diversify further, to bring into our gardens different fruits and nuts to spread the risks and to widen our diets with more nutrients, flavours and textures. And we need to develop better varieties. The apple of today comes from the miserable crab, the strawberry we enjoy did not exist two hundred years ago in either size or flavour. Look to the fruits of the future, those edible berries that have not yet been selected and bred. You could be the breeder to introduce the new huge super-sweet elderberry, the most luscious fuchsia fruit or the biggest, tastiest rose hip ever.

No greater good can one achieve than to feed others, not only with their need but for their delight.

FRUITS AND GARDENS: THEIR HISTORY IS AS ONE

Our earliest diet as hunter-gatherers, millions of years ago, must have included a wide range of seeds, fruits, nuts, roots, leaves and any moving things we could catch. As we lived for the great bulk of the time, according to theory, in warm areas, we would almost certainly have eaten much fruit in our diet. A warmer climate means more fruit in variety all year round.

Nomadic peoples learned to follow circuits to coincide with flushes of food. And of course, seemingly by magic, when they returned to a previous campsite they would find their favourite fruit trees and bushes waiting for them. Moreover, these trees and bushes would be more prolific than wild ones, as the magic trees would be growing on the immensely fertile site of the tribes midden or waste heap.

Thus, as early populations perambulated, they spread the very plants that sustained them. In those early days the pickings must have been glorious, with vast areas swathed in ripening fruits. But as populations grew, the consequent demand for land caused them to spread to colder and drier regions.

The hunter-gatherer lifestyle became difficult in temperate zones as there is little plant food naturally available for half the year. We developed livestock as a means of storing the food, the summers harvest becoming winter meat and cheese. Animal culture had other advantages; it was a more readily exchangeable form of wealth, mobile and in season all year round. If enemies threatened, you could head for the safety of the hills with your flocks.

It is no good planting an orchard if you are unsure of next month, let alone next year. As annual crops were more sure than perennial, farming for cereals and quick-return crops predominated and gardens were rare except where civilisation was long established, such as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Thus the development of gardening and fruit culture serves to characterise times and places of peace and stability.

The Classical Greek period was a time of wars and there was little chance of gardening. The Roman Empire was the longest time of (relative) peace known. The Romans enjoyed most of our everyday fruits in abundance. They had the apple, pear and quince, the peach, plum, cherry and almond, the mulberry and the grape on sale in their streets and markets along with figs, dates, olives and exotic fruits from around the Mediterranean and North Africa.

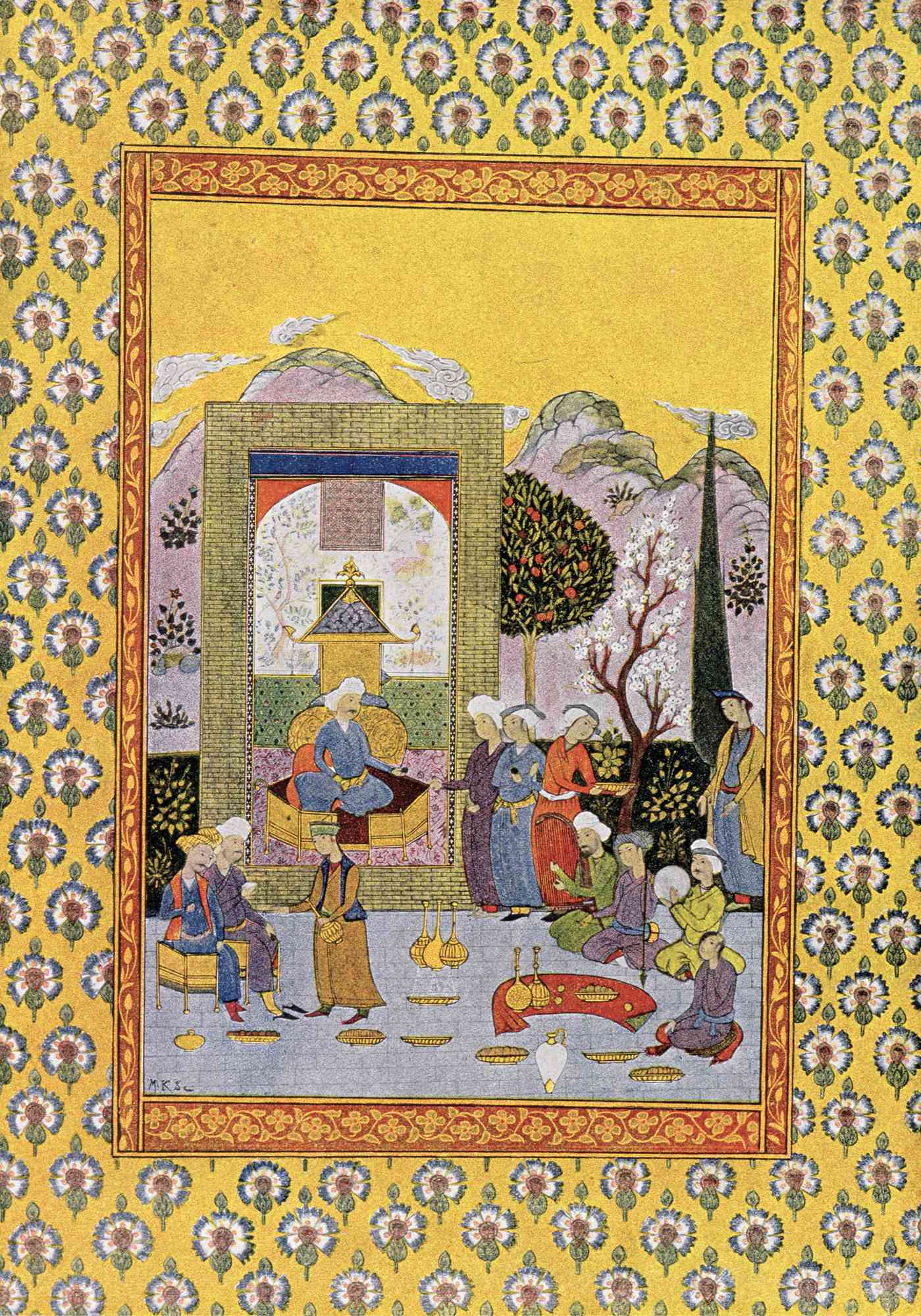

One of the earliest places in which gardens developed was the Arab courtyard. Centred on water, representing an oasis, and protected by shading walls, their gardens were planted with the fruit trees, flowers and plants they adored. Their influence extended throughout the Middle East and into the Mediterranean region and trade with Rome. Their fruit gardens were emulated by the Romans, but in more extravagant style. Roman gardens were built around water, fruit trees, bushes and especially vines, and they introduced the idea of organising a garden into areas, inventing the herb garden and the orchard. After the Roman civilisation crumbled, northern Europe entered the Dark Ages. The violence of the period worked against the cultivation of fruit, and almost all the knowledge of the Romans was lost, along with most of their varieties. The little that was preserved was due to the monasteries and royal gardens.

Rich and powerful individuals have always had their own, usually well protected, private gardens. These were often viewed very pragmatically, being usefully filled with fruiting plants and herbs. Many a tyrant prefered to eat fruits he could watch daily, and thus ensure their freedom from poison, and if the oppressed did revolt there was a ready food supply till help arrived.

The monasteries similarly guarded fruits and herbs for their own use and also for their medicinal value. In a time of frequent famine and annual winter dearth, the commonplace scurvy and vitamin deficiencies would have seemed to many people almost miraculously cured by monks potions containing little more than preserved fruits full of nutrients and vitamin C.

By the time of the Norman invasion, England had become a farming and herding society. The civilising influence returned and brought back gardens and orchards, mostly to provide the cider which necessarily replaced wine. Most great houses and manors had gardens for fruit, herbs and vegetables.

The Crusades reintroduced Mediterranean fruits which had been forgotten since the Romans and interest in gardening was rekindled. The Low Countries specialised in fruit and market gardening and developed many new varieties during the next centuries. Henry VIII actively encouraged the planting of orchards and fruit gardens to try to break the Dutch monopoly, but they have reigned on and still are the centre of world horticultural trade.

Next page