To Henry John William and Chloe Elizabeth Matthew Biggs

To Mac, Hannah and Alistair Jekka McVicar

To all those who helped make our glorious fruits from such humble beginnings Bob Flowerdew

INTRODUCTION

A flourishing, productive garden, containing vegetables, herbs and fruit plants, is a testament to diligent, imaginative gardening and a promise of a delicious harvest to come. The range of colour, texture, scent and flavour offered by these plants is unrivalled, and there is space in any garden even in a window box for a selection of edible and useful plants.

Vegetables, herbs and fruit have always been essential to humanity. They are the basis of the food chain even for meat-eaters and are a vital component in creating tempting, palatable meals, as well as providing unique flavouring and aromas. All are health-giving, providing essential vitamins and minerals for a balanced diet, and many herbs have the added dimension of being used medicinally.

Vegetables and herbs can be widely defined. Vegetables are those plants where a part, such as the leaf, stem or root, can be used for food. Herbs, similarly, are those plants that are used for food, medicine, scent or flavour. Fruits tend to be the sweet, juicy parts of the plants, containing the seed. There is considerable overlap between the three types of plant one further distinction is that fruits are generally sweet, or used in sweet dishes, while vegetables are savoury, although this is by no means clear-cut.

For centuries throughout the world, productive gardens have been the focal point of family and community survival. Our earliest diet as hunter-gatherers must have included a wide range of seeds, fruits, nuts, roots, leaves and any moving thing we could catch. Gradually, over millennia, we learned which plants could be eaten and how to prepare them as with the discovery that eddoes were edible only after being washed several times and cooked to remove the injurious calcium oxalate crystals. Fruit trees and bushes sprang up at the camp sites of nomadic people and were waiting for them when they returned, growing prolifically on their fertile waste heaps. Vegetables and herbs were collected from the surrounding countryside, and gradually were domesticated. Cultivated wheat and barley have been found dating from 8000 to 7000 BC , and peas from 650 BC , while rice was recorded as a staple in China by 2800 BC .

With domestication came early selection of plants for beneficial characteristics such as yield, disease resistance and ease of germination. These were the first cultivated varieties, or cultivars. This selection has continued extensively and by the eighteenth century in Europe, seed selection had become a fine art in the hands of skilled gardeners. Gregor Mendels work with peas in 185564 in his monastery garden at Brno in Moravia yielded one of the most significant discoveries, leading to the development of hybrids and scientific selection. Most development has centred on the major food crops. Minor crops, such as seakale, have changed very little, apart from the selection of a few cultivars. Others, like many fruits, are similar to their wild relatives, but have fleshier, sweeter edible parts. Herbs have in general had less intensive work done on selection; many of the most popular and useful herbs are the same as or closely related to plants found in the wild.

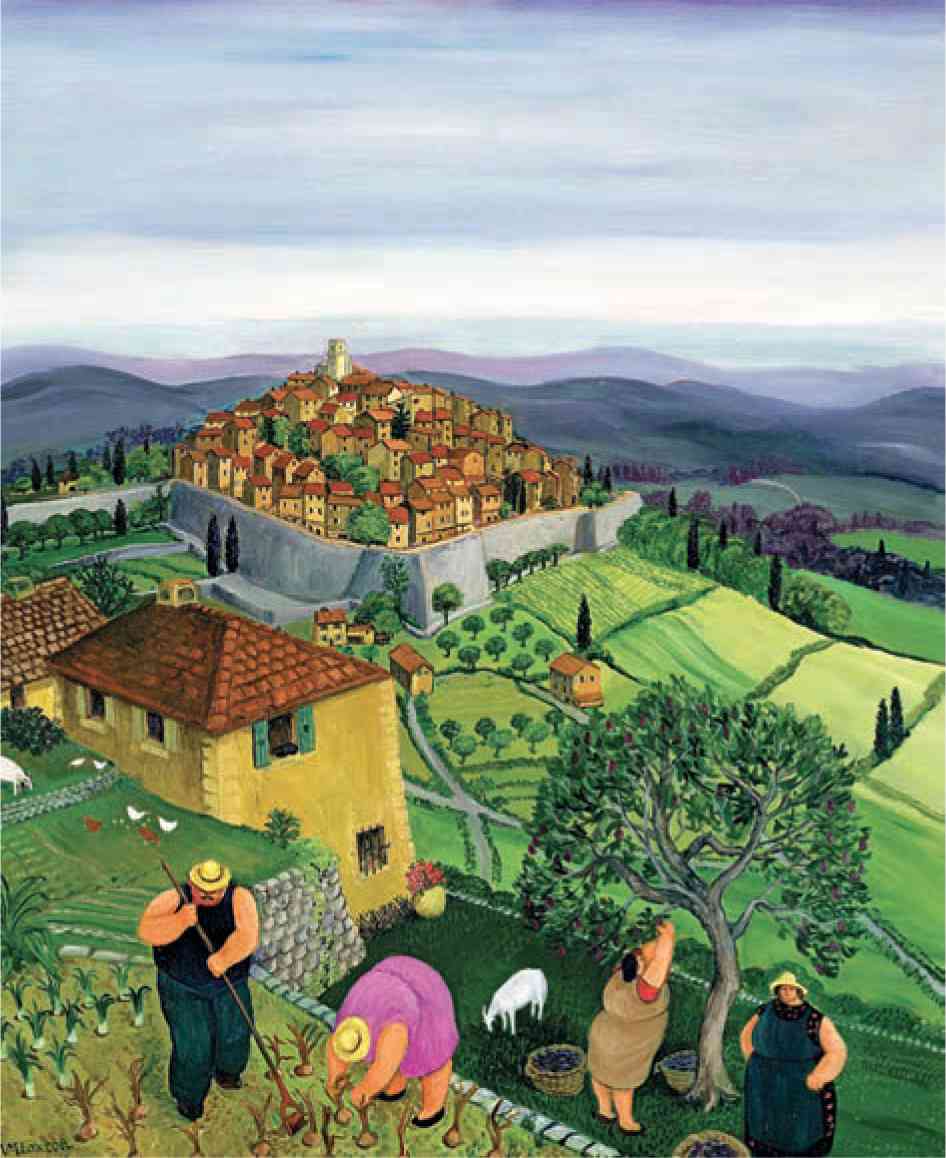

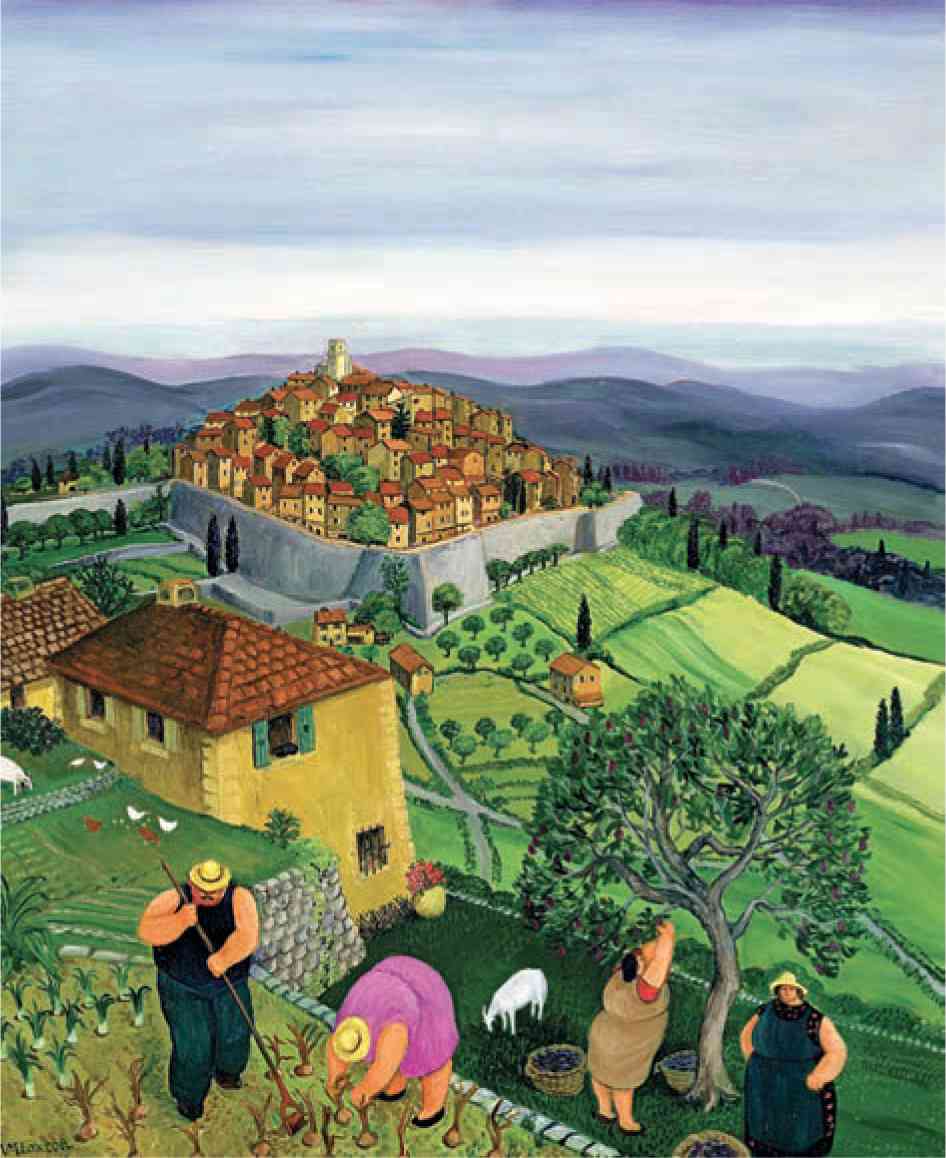

The Vegetable Garden, Coombe by Paul Riley, 1988

Food plants have spread around the world in waves, from the Roman Empire, which brought fruits such as peaches, plums, grapes and figs from the Mediterranean and North Africa to northern Europe, to the influx of plants such as potatoes and maize from the New World in the fifteenth century. In between, monasteries guarded fruits, vegetables and herbs for their own use and for their medicinal value. During the famine and winter dearth of the Middle Ages and beyond, the commonplace scurvy and vitamin deficiencies would have seemed to many people almost miraculously cured by monks potions containing little more than preserved fruits, vegetables or herbs full of nutrients and vitamin C. In 1597 John Gerard wrote his Herball , detailing numerous plants and their properties, and giving practical advice on how to use them.

Productive gardening developed on several levels. The rich became plant collectors and used the latest technology to overwinter exotic plants in hothouses and stovehouses. Doctors followed on in the traditions of the monasteries and had physic gardens of medicinal herbs. Villagers had cottage gardens filled with fruit trees and bushes, underplanted with vegetables and herbs.

In the twentieth century, the expense of labour and decrease in the amount of land available meant that productive gardening declined. Home food production revived during the Second World War, but the availability of ready-made foods afterwards again hit edible gardening at home. The later years of the twentieth century saw a reaction against the blandness and cost of mass-produced food. There was also an increasing awareness of the infinite variety of herbs, and their use in herbalism, cosmetics and cooking all over the world.

St Paul de Vence by Margaret Loxton

The wider realisation that we had polluted our environment and destroyed much of the ecology of our farms, countryside and gardens was to bring about a real revolution. A mass revulsion against chemical-based methods was mirrored in the rise of organic production and the slowly improving availability of better foods. Vegetarianism also increased as many people turned away from meat, in part because of factory farming. These trends have meant that there is now an increased demand for fruits and vegetables, often organically produced or with a fuller flavour, and supermarkets now offer a huge range all year round.

But there has also been a move towards people growing their own. The health benefits, ecology and economy of gardening appeal to a greener generation. Increased awareness of alternative medicine, including herbalism and aromatherapy, has revived interest in a range of herbs. With food processors, juicers and freezers, it is easier than ever to store and preserve what we harvest. In addition, the genetic richness represented by the huge range of food plants has been recognised and organisations such as the Henry Doubleday Research Association in the UK, Seed Savers in the USA and Seed Savers Network in Australia are working to safeguard and make available the old and rare varieties.

The availability of different gardening techniques also offers great opportunities at home. Dwarfing fruit rootstocks, varieties that store well or resist disease, glass or plastic cover, and controlled heating in greenhouses give us scope to grow a huge variety of crops, even in a small garden. The earlier and later seasons also mean that we can be planting and harvesting for a larger proportion of the year.

This book is intended to guide the reader in choosing which vegetables, herbs and fruit to grow, and then in producing a crop successfully. The vegetable and herb sections are arranged alphabetically by the botanical Latin name. The fruit section is grouped into five chapters covering different types of fruit plants Orchard Fruits, Soft, Bush and Cane Fruits, Tender Fruits, Shrub and Flower Garden Fruits, and Nuts.

Under each plant, after a brief introduction covering origins and history, the most useful and recommended varieties are given, followed by details of cultivation, including propagation, growing in containers, a maintenance calendar, pruning and training (if needed), dealing with pests and diseases, companion planting and harvesting and storing. Information and ideas are given for using the plant, including recipes and medicinal and cosmetic uses. If any part of the plant is toxic or harmful in any way, a detailed warning is given. If the plant is of particular ornamental or wildlife value in the garden, this is indicated. The fruit and vegetable sections also cover tropical and sub-tropical crops.