Rachel Aspden - Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East

Here you can read online Rachel Aspden - Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Other Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

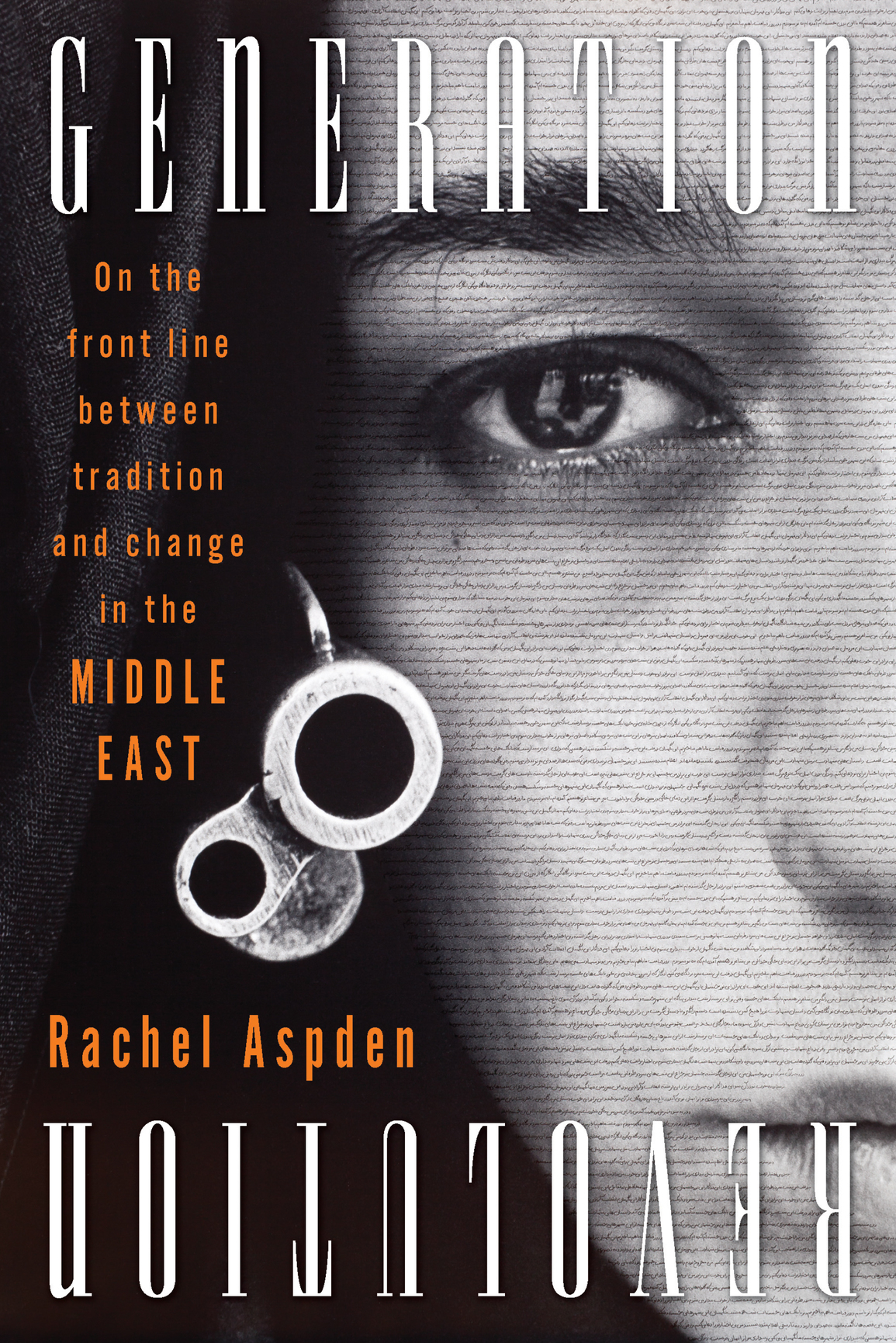

- Book:Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East

- Author:

- Publisher:Other Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rachel Aspden: author's other books

Who wrote Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright Rachel Aspden 2016

First published in Great Britain by Harvill Secker in 2016.

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site:

www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Aspden, Rachel, author

Title: Generation revolution : on the front line between tradition and change in the Middle East / Rachel Aspden.

Description: First American hardcover edition. | New York : Other Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016024349 | ISBN 9781590518557 (hardcover)

| ISBN 9781590518564 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: EgyptHistoryProtests, 2011- | EgyptSocial

conditions21st century. | RevolutionsEgyptHistory21st century.

| YouthPolitical activityEgyptHistory21st century. | Youth

EgyptSocial conditions21st century.

Classification: LCC DT107.88 .A76 2016 | DDC 962.05/5dc23 LC

record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016024349

Ebook ISBN9781590518564

v4.1

a

For the people of Egypt who showed me so much kindness.

And for my grandparents.

I am proud of you as the new generation calling for a change for the better, dreaming and making the future.

Hosni Mubarak, president of Egypt,

televised address to protesters, February 10, 2011

If the people one day wanted to live then destiny must respond and the night must fade away and the chains must break.

Tunisian poet Aboul Qassim Echebbi (190934),

lines adopted as a chant in the Tunisian uprising of late

2010, then in protests in Egypt, Syria and Iraq

As the twenty-first century began, Egypt was ruled by old men. The president, Hosni Mubarak, was well into his seventies. Aging generals, bureaucrats and businessmen ran everything from the army to universities, tourist resorts and oil and gas installations. Even the leader of the most popular opposition movement, the banned Muslim Brotherhood, was the same age as Mubarak. And each of these men in his spherefrom police officers to religious scholars to fathersexpected deference and unquestioning obedience.

But Egypt was young. Of the 70 million Egyptiansa population that dwarfed every other in the Middle East except those of Iran and Turkeyalmost two-thirds were under thirty. They had no political voice, limited job prospects and less hope. A gap was opening up between them and the men who controlled their lives.

I first arrived in Egypt in the autumn of 2003. I was twenty-three, I had just graduated and, six months earlier, I had watched on the television news as coalition tanks rolled into Iraq. This struggle, British prime minister Tony Blair told us, was existential, our enemy the Islamic extremists who detest our freedom, democracy and tolerance. The solution? Exporting, by force if necessary, what he called the universal values of the human spirit.

I wanted to discover some of the truth about the Middle East for myself, and Cairo, the sprawling ancient city at its heart, was my starting point. I had never been to Egypt before, I knew no one and I spoke no Arabic, but I was eager to learn and ready for adventure. So I enrolled in a scruffy Arabic school and found a low-paid job on an English-language news magazine with two bored secret policemen parked permanently outside the office, smoking cheap cigarettes and eating chicken shwarma sandwiches.

I had landed in a desert in the deep freeze. Mubarak, a former air-force officer, had been in power for twenty-two years. All power and money flowed through the army and those close to it. Beyond its circle of privilege, half the population scraped an existence below or on the poverty line, and all but the wealthiest struggled with soaring food prices, unemployment, corruption and crumbling public services.

This status quo was cemented by around $1.5 billion of American aid a year, the political support of the West and the rich Gulf monarchies, and the sprawling military, police and intelligence apparatus this patronage had helped create. It was hard to see how it could ever change. Political participation was tightly controlled, and dissenters risked abduction, torture, imprisonment or even death. It was a scene replicated across the Middle East. Though Saddam Hussein had just been removed by the United States, his fellow dictatorsMuammar Gaddafi in Tripoli, Bashar al-Assad in Damascus, Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunis, Ali Abdullah Saleh in Sanaa and the monarchs in their gleaming Gulf citieslocked the regions balance of power in place.

But I could see that in other ways Egypt was on the point of change. Burger Kings, Costa Coffees and Starbucks were opening in middle-class districts, satellite TV channels were multiplying and more and more Egyptians had access to the Internet. It was getting harder for the regime to isolate them from new ideas and from each other, and to keep their desire for a share of the freedom and prosperity they saw on their screens in check.

The graduates of my own age who I met intrigued me. In some ways our lives were alikewe used the same phones, watched the same Hollywood films, wore the same trainers and ate the same fast foodbut they were struggling with very different pressures that flowed from the revival of conservative Islam and the deep-rooted traditions that still governed Egyptian society. They wanted to feel part of the twenty-first-century globalized world, but alsoseeing the West invade their region and criticize their faith while propping up Egypts corrupt and repressive governmentto defend their identities as Muslims, Arabs and Egyptians. Religion and consumerism, tradition and modernity were pulling them in painfully different directions.

I began to think that their answers to these dilemmas would determine much about the regions future. If I wanted to understand more about the Middle East, I needed to listen to them.

I left Egypt in 2005 to work for a news magazine in London and spent the next six years traveling between the UK and the Middle Eastthrough Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine, down to Sudan and across to the Gulf and Yemen. The stories of the young people I met reflected the same conflicts I had first heard about in Egypt, to where I found myself returning again and again. I started tracing the lives of a handful of young Egyptiansdevout or atheist, apolitical or activist, conservative or liberal, but all middle-class city-dwelling students and graduates who were not isolated from outside influences like the rural poor or insulated from dysfunction like its country-hopping elite. In twenty or thirty years they would be leading their country, and I wanted to see where they would take it. The first half of this book follows them through the last years of Mubaraks Egypt, as they created the conditions for change.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East»

Look at similar books to Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Generation Revolution: On the Front Line Between Tradition and Change in the Middle East and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.