sorry something went wrong loading your content. Check the table of contents or try paging forward. Or contact us at support@bookshout.com

Acknowledgments

In the process of this study I have consulted a number of people who willingly gave advice and assistance. I am grateful to all of them, and acknowledge my debts: to Marcia Epstein, Robert Taylor, and Dennis McAuliffe, who assisted me with translations; to Margaret Bent, Thomas Binkley, Edmund Bowles, Ingrid Brainard, Fredrick Crane, Andrew Hughes, Timothy Rice, and George Sawa, who provided musicological assistance of various kinds; to the Toronto Consort and numerous other performers who played the dances and discussed the music. I am indebted to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for supporting the research and for providing funds to have the music prepared. The final copy of the music was done by Robert Mazur using the MusScribe program developed by Keith Hamel.

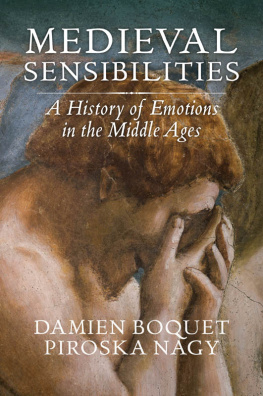

D ANCE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

THE EVIDENCE

Curt Sachs describes and documents the tradition of dancing as a function of religious worship as well as recreation in many cultures from earliest recorded history.

Information concerning secular dance in the late Middle Ages has survived in a variety of sources. Iconographic evidence, such as the manuscript miniatures and frescos reproduced in Plates 14 and the frontispiece, provides images of dancing individuals, couples, and groups. A few scattered letters and diaries survive from the period containing such entries as: Each evening the Signore calls them together with the trumpets and harps and lutes, and he dances until two oclock. The following excerpts from three of the best-known fourteenth-century writers in England, France, and Italy further demonstrate the scope and variety to be found in literary references:

Ful curteysly she called me,

What do ye there, beau sire? quod she,

Come, and if it lyke you

To dauncen, daunseth with vs now.

And I, without taryeng,

Went into the karollyng.

Chaucer

Some sang pastourelles about Robichon and Amelot, others played on vielles chansons royal and estampies, dances and notas. On lute and psaltery each according to his preference [played] lais of love, descorts and ballads in order to entertain those who were ill.

Maillart

When they had put away the tables, since all the young men and women knew how to carol, play instruments and sing, and some of them really well, the queen commanded that the instruments be brought, and at her command Dioneo picked up a lute and Fiametta a vielle, and began sweetly to play a dance. At that, after they had sent their servants away to eat, the queen and the other women, together with two young men, made a circle and with slow steps began to dance the carol.

Boccaccio

All these kinds of evidence are helpful in providing a general impression of dance, but their use is limited. Archival sources such as those that attest to the presence of religious dancing are useful in determining the varieties of settings that included dance and some of the people who participated. At present we cannot be sure that the couples in Plate 3 are dancing at all; they may be merely processing in the garden. And the upside-down youth in Plate 4 may be a tumbler.

References in the letters and literature of the period supply names of dances and descriptions of dance formations, steps, instrumental accompaniment, and the occasions on which dancing took place. We can see in the earlier quotations, for example, that the carol was danced in all three countries, and that on occasion it followed dinner; Boccaccio even tells us that the dancers form a circle to dance the carol. Numerous additional quotations could be cited that would add minor refinements to the above information.

What one can learn from iconographic depictions of the vivid, frozen images of dancers, and from the colorful literary descriptions, remains mostly at the general level. They do not provide the specifics of tempo, duration, and step sequence needed for a detailed understanding of medieval dance. But when combined with the theoretical sources and an analysis of the surviving dance repertory, even some of these facts can be deduced, and the composite picture assembled here, although still incomplete, contains far more details than had previously been suspected.

Plate 1. The Effects of Good Government (detail), Ambrogio Lorenzetti (133739). Siena, Palazzo Publico. Courtesy Art Resource.

Plate 2. Church Militant (detail), Andrea di Bonaiuto (1365). Florence, Spanish Chapel, Santa Maria Novella.

Plate 3. Fresco (ca. 1420). Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio. Per concessione del Museo Provinciale dArte di Trento.

Plate 4. Music in the Garden of Delight , Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, Le Roman de la Rose. Valencia, Biblioteca Universitaria, MS 387, fol. 6v.

On a larger level, the surviving evidence also contributes to a perception of the general spirit of dance and its importance in the lives of the citizens of the late Middle Ages. The bulk of the information is in reference to the aristocracy, for it was they who commissioned the books and paintings and kept the records. (For these reasons it is probable that the music printed here is representative mostly of that class.) But occasionally there is a reference to other classes, from which we learn that dance was for all an important and frequent activity.

THEORETICAL STATEMENTS AND THE DANCE REPERTORY

Vocal and instrumental dances existed side by side throughout the era and obviously influenced one another; indeed it is not always possible to separate information about one from that for the other. The names and descriptions of some of the vocal and instrumental dances are identical, and it would appear that in terms of function and form they were closely related. In the discussion to follow, therefore, I have frequently pooled all available information about both vocal and instrumental dances in order to arrive at a better understanding of dancing in the Middle Ages and the nature of the music in this volume.

Vocal Dances

In the opinion of a number of scholars, the most popular secular poetic forms of the late Middle Ages were intimately connected with dance. Similarities have been noted between the poetic formal schemes and those of known dances.

Secular music survives in all these forms. The bulk of the earliest surviving works are in the troubadour/trouvre repertory, and they remained popular secular forms in France, Italy, and England until the end of the fifteenth century. But these forms, which may have been dances in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries or earlier, seem to be quite removed from any association with dance music by the time we find most of the musical examples, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The later repertory is sophisticated art music matching the theoretical descriptions of the formal design of the earlier dance compositions, although rarely exhibiting the kind of melodic and rhythmic patterns that would suggest the dances described in the earlier literary and theoretical accounts. The relationship of the earlier forms to the more sophisticated later examples is demonstrated by some of the earliest vocal dances with music, for example, the Latin rondeaux at the end of the Florence copy of the Notre Dame repertory

The clearest theoretical description of vocal dances was written by Johannes de Grocheio, in his De Musica, ca. 1300. Example 1 conforms to Grocheios definition of round because the refrain lines are set to melodic phrases that are also used as part of the verse melody. His round, in fact, describes not only the rondeaux form but also the virelai and the ballade, since all three set the refrain lines to music also used for the verses. Grocheio has grouped these three forms under the common heading round dance even though they have different specific formal schemes, probably because they are danced in a similar fashionin the round. The carol, the remaining poetic form related to dance, has a somewhat different musical form and dance formation, as we shall see below.

Next page