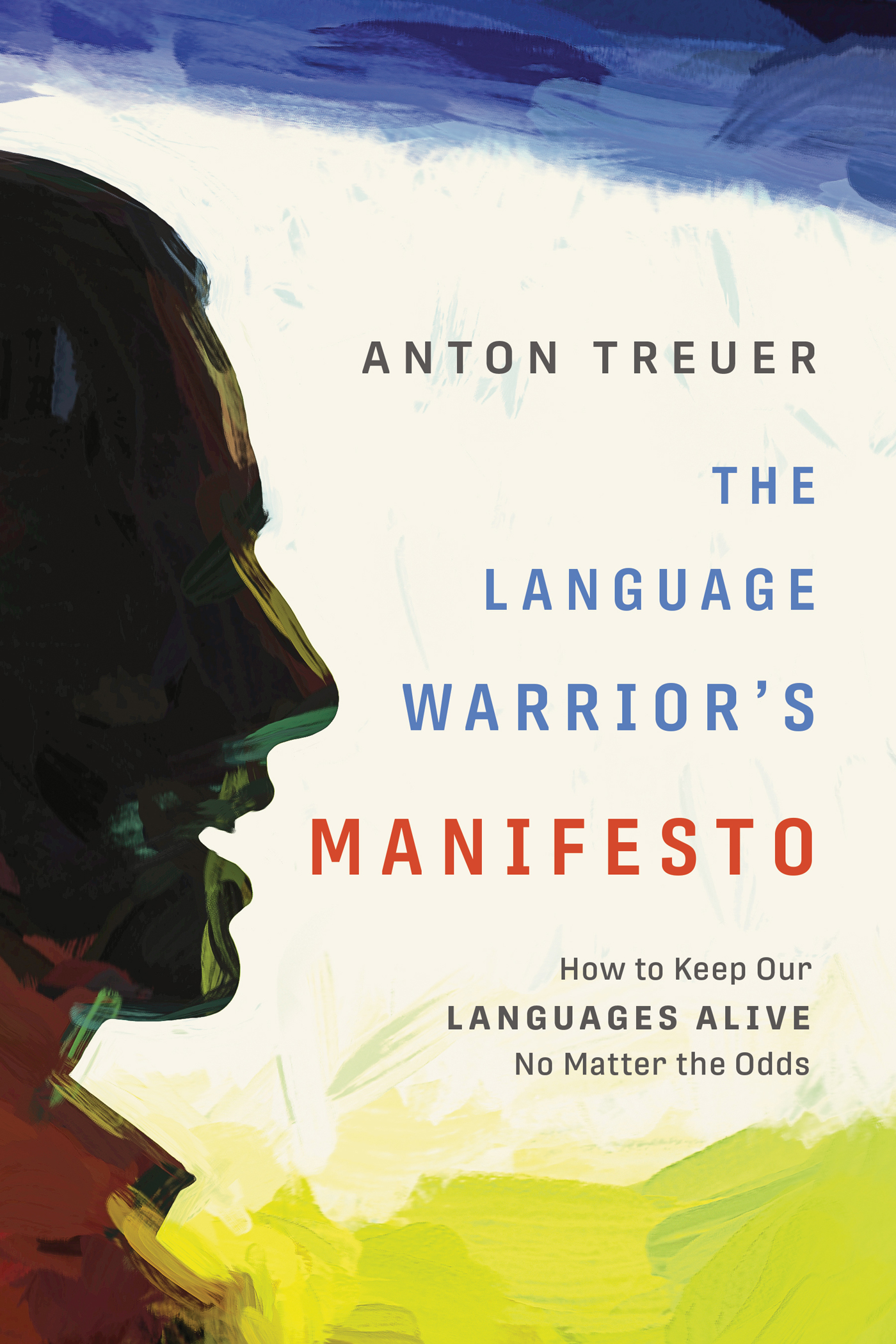

THE

LANGUAGE

WARRIORS

MANIFESTO

THE

LANGUAGE

WARRIORS

MANIFESTO

How to Keep Our

Languages Alive

No Matter the Odds

ANTON TREUER

Text copyright 2020 by Anton Treuer. Other materials copyright 2020 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-154-5 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-155-2 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

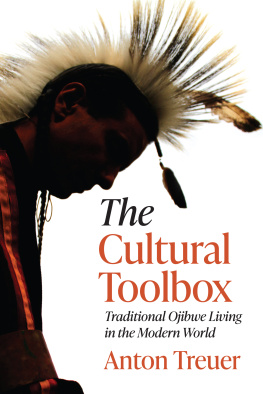

Names: Treuer, Anton, author.

Title: The language warriors manifesto : how to keep our languages alive no matter the odds / Anton Treuer.

Description: Saint Paul : Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: Anton Treuer has been at the forefront of the battle to revitalize Ojibwe for many years. In this impassioned argument, he discusses the interrelationship between language and culture, the problems of language loss, strategies and tactics for resisting, and the inspiring stories of successful language warriors. He recounts his own single-minded and sometimes hilarious struggle to learn Ojibwe as an adult, and he depicts the astonishing success of the language program at Lac Courte Oreilles in northern Wisconsin, where dedicated families and teachers have raised a hundred children who speak Ojibwe as their first language. This is a manifesto, a rumination, and a rallying cry for the preservation of priceless languages and cultures.Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019040790 | ISBN 9781681341545 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681341552 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Language revivalAmerica. | Language and cultureAmerica. | Ojibwa languageStudy and teaching. | Treuer, Anton. | Ojibwa IndiansBiography.

Classification: LCC P40.5.L3572 A455 2020 | DDC 306.44dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019040790

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

For Giizhigookwe,

my daughter, Madeline Treuer,

who taught me love at its deepest

and inspiration in the highest.

Gizaagiin, daanis!

CONTENTS

THE

LANGUAGE

WARRIORS

MANIFESTO

FINDING FIRE

I AM NOT A LIKELY CANDIDATE FOR TEACHING, OR EVEN HAVING much to say about, our language and ways. My father, Robert Treuer, was a white man who spoke nothing but German the first thirteen years of his life. My mother, Margaret Treuer, is Ojibwe and grew up in the heart of the Leech Lake Reservation, but like many in her generation, she was the child of parents who spent their formative years in residential boarding schools, where the language was forbidden. Her family experienced hard living, incredible poverty, and the beauties and struggles of reservation life during the Great Depression and World War II. For generations, nobody in my family and few in my community had received their Ojibwe language and culture as a birthright. I never attended a school that had a real tribal language program. Today I should not know my language, culture, or ceremonies.

But I do know my language, culture, and ceremonies. I speak Ojibwe fluently. Im not as eloquent as some of our great surviving speakers today. But I officiate at our Medicine Dance, telling legends that are hours long entirely in Ojibwe. I routinely converse in Ojibwe with great speakers from all over Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ontario, and Manitoba. Ive written books in Ojibwe. I dream in my language.

And I am not alone. On the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation in Wisconsin, a number of families, teachers, and other language activists have done something that hasnt been done there since World War II: they raised a child who speaks Ojibwe as a first language. And its not just one child, its over one hundred. They speak our tribal language, a language that most of their parents and grandparents do not speak.

My story and the story of communities like Lac Courte Oreilles are not isolated developments. They are part of an upswell, a resurgence, a revitalization of indigenous languages and cultures started by language warriors in many places. Their stories are incredible. They are inspiring. And they point the way.

I have a personal narrative to share with you. I share it not because I see any superlative significance in my accomplishments, but because I know my story and I believe it can impact yours. I also share it because in my connections to the journeys and wisdom of others who are deeply engaged in this work, I have found cause for hope and tools to do the work. Our languages can live.

Five hundred years ago, Europeans came to America and announced, Those Indians aint gonna last. Theyve kept saying it every year since. And for five hundred years in a row, the Europeans have been wrong. There is nothing as powerful as a living tribal language to prove that point. One of my mentors, the late, great Thomas Stillday of Ponemah, Minnesota, always had a poignant way to do it. I convinced some of the administrators at Bemidji State University, where I work, to bring him in to give the keynote speech at our annual American Indian Awards Banquet. He immediately broke all the rules for banquet speeches, which are supposed to be short, include a couple of good jokes, and focus on the students. He spoke for over an hour and a half, and he did the whole thing in Ojibwe. When he was done, he said only one thing in English: All you people who study Indians, study that! And then he sat down. Although the eyes of many people at the event had thoroughly glazed over during his speech because they were monolingual English speakers, his message must never be forgotten. Our languages live. And although many of our own people do not speak our languages, through no fault of their own, the keys to accessing and understanding indigenous thought are our natural instruments of human speechindigenous languages.

All humans have ancestors. But most immigrants, especially in a place like America, are disconnected from them. Most people know their parents and grandparents, and the names of their great-grandparents. But beyond that, they usually dont know their ancestors names or even where they are buried. My relatives have been buried in the Bena Cemetery on the Leech Lake Reservation since before America was a country. That makes it hard to sell the family farm and move to California. But for white Americans, thats how its done. If the job is in California, people move. They celebrate the freedom to have a malleable identityto become Californian. When their kids move to different states, far from the parents, they try to keep it real with their grandkids through Facebook and FaceTime. Over time, the connections to place and across generations weaken.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.