Copyright 2019 Fortress Press, an imprint of 1517 Media. Published in association with Creative Trust Literary Group, 210 Jamestown Park, Suite 200, Brentwood, TN 37027 www.creativetrust.com. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Email copyright@1517.media or write to Permissions, Fortress Press, PO Box 1209, Minneapolis, MN 55440-1209.

You can see my photographs from the trip by going to brianmclaren.net/galapagosphotos. Thanks to Julie Pelletier (p. 82), my Swiss travel companions (p. 120), and Ron Dunn (p. 172) for use of their photos included in this book. All other photos are courtesy of my iPhone 7.

This book is dedicated to my father, Dr. Ian D. McLaren (19242014). He loved the outdoors, and he was always ready for an adventure. How many mountain trails did I hike, lakes did I canoe across, impromptu picnics did I enjoy, and crackling campfires did I help build because of his contagious energy and love for life? My life has overflowed with so much joy because he was my dad.

This book is also dedicated to my friend and mentor, Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM. He teaches that creation is the original Bible, and he knows that the door that opens outward into creation also leads us inward into holy contemplation.

Finally, this book is dedicated to my grandson, Lucas McLaren Stone, who inherited my love for all things alive. I smile to think that he will be watching tortoises, listening for birdsongs, and following the flight of dragonflies long after Im gone. Lucas, his sisters Ella and Ada, and his cousins Averie and Mia inspire me to protect this beautiful earth, for them and for their grandchildrens grandchildren.

This book entered my life as a surprise, a needed surprise in an unpleasant situation.

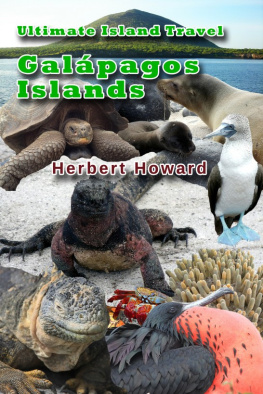

My friend Tony Jones, an insightful theologian, gifted writer, and skilled editor at Fortress Press, contacted me with an idea. He was planning a series of books that would be one part travel guide, one part spiritual memoir, and one part ethical/theological reflection. Would I be willing to launch the series, he asked, with a book on the Galpagos Islands?

I cant pay you an advance, he said, but I can cover your expenses.

Let me think about it and get back to you, I replied. But I didnt need much convincing.

I immediately thought of Anthony Bourdain, vigorously alive then, but gone a few months later. Bourdains show Parts Unknown delighted millions by bringing together travel and a love for food. Similarly, the late Steve Irwins show The Crocodile Hunter combined travel with a love for interacting with wildlife. Why not combine travel with a love for justice, compassion, goodness, wonder, and God? Tonys idea made perfect sense to me.

After all, from Exodus to the story of the prodigal son, the spiritual life has been understood as a journey. The Gospels and Acts read as travel stories following Jesus around Palestine and Paul around the Mediterranean. Even today, people love reading tweets and blog posts about twenty-first-century experiences on the Camino de Santiago, just as they loved to read Canterbury Tales in the fourteenth century. Spirituality and travel have a long history of going together.

So as an avid traveler with deep spiritual commitments, this assignment felt like a good fit for me personally.

It felt like a good fit professionally as well.

For the last twenty years, Ive been writing about the postmodern/postcolonial turn and the challenges and opportunities it presents to people of faith, and especially Christians. This turn, among other things, involves a recognition that behind every statement there is a story, a story of struggle and joy, quest and conquest, oppression and liberation, predicament and opportunity. And every story has a setting, so settings matter.

The postmodern turn challenges us to see from the start that all theology and spirituality (like all politics, economics, and other human endeavors) are situated, with all the limitations and benefits being situated brings. Where you do your theology and where you practice your spirituality will have a profound effect on you and the outcome of your endeavors. If you live on a farm in a tropical setting, you will experience the world and life and God differently from people who spend their lives in a refugee camp in a harsh desert, at a trading outpost above the Arctic Circle, or on the twenty-sixth floor of an urban skyscraper. Every viewpoint is a view from a point, a postmodern mantra says, which doesnt mean (as is often accused) that everything is equally true (or false) but rather that every person or group sees and speaks from a perspective, a situation.

Travel is still the most intense mode of learning. Kevin Kelly |

Each situation has advantages and disadvantages. If you engage in theology and spiritual practice from a situation of power and privilege at the top of the social and economic pyramid, for example, you will see whats visible from that lofty perspective, but you will miss a lot too. If you work from a situation of oppression and struggle at the bottom, lugging the bricks to build the pyramid upon which elites are perched, you will see things from that perspective that those at the top cant imagine.

Similarly, spiritual and theological work done in solitude will differ from work done in community, and homogenous or authoritarian communities will likely produce conclusions that differ greatly from work done in communities of diversity and freedom. Its not that one situation is purely good and all others are bad, but rather, that all situations are simultaneously unique and limited, which argues for all of us to listen to people who see and speak from different situations and, when possible, to put ourselves in different situations through travel.

We want to experience the earth firsthand, to feel the wind on our face, plunge into the mountain waters, enter into virgin forest, and capture the expressions of biodiversity. An attitude of enchantment is resurfacing, a new sense of the sacred is reemerging. Leonardo Boff |

Meanwhile, our spiritual and theological lives arent shaped by our social, economic, or cultural location alone. Even our environmental context will influence the kind of theology and spirituality we profess and practice.

Most theology in recent centuries, especially white Christian theology, has been the work of avid indoorsmen, scholars who typically work in square boxes called offices or classrooms or sanctuaries, surrounded by square books and, more recently, square screens, under square roofs in square buildings surrounded by other square buildings, laid out in square city blocks that stretch as far as the eye can see. If practitioners of this civilized indoor theology look out at the world, it is through square windows or in brief moments between the time they exit one square door and enter another. But those outdoor times are generally brief, so these days, this square theology exists almost exclusively in heated and air-conditioned spaces that maintain a pleasant and consistent seventy-two degrees, whatever the season or latitude.