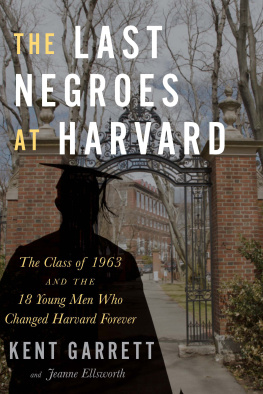

Kent Garrett - The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever

Here you can read online Kent Garrett - The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: HMH Books, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever

- Author:

- Publisher:HMH Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Kent Garrett: author's other books

Who wrote The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2020 by Kent Garrett Productions, LLC

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garrett, Kent, author. | Ellsworth, Jeanne, 1951 author.

Title: The last negroes at Harvard : the class of 1963 and the 18 young men who changed Harvard forever / Kent Garrett and Jeanne Ellsworth.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019014973 (print) | LCCN 2019021933 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328880000 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328879974 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH : Harvard UniversityStudentsHistory20th century. | African American college studentsMassachusettsCambridge. | African AmericansEducation, HigherMassachusettsCambridge. | Harvard UniversityHistory20th century. | Discrimination in higher educationUnited StatesHistory20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | EDUCATION / Higher.

Classification: LCC LD 2160 (ebook) | LCC LD2160 .G 37 2020 (print) | DDC 378.1/982996073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019014973

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson

Harvard photograph Barry Winiker / Getty Images

Student photograph Paul Barton / Getty Images

Author photograph Jill Ribich

v1.0120

Photos from Class of 1963 Register, Class of 1963 Harvard Yearbook, and Class of 1963 Radcliffe Yearbook used with permission by Harvard Yearbook Publications, Inc. All other uncredited photographs courtesy of the author/Kent Garrett Productions LLC.

For Jack Butler

For most of my life, Ive claimed that I rarely thought about Harvard. As evidence, I would eagerly tell you what a lousy alumnus Ive been. I hadnt given the school a nickel, hadnt gone to a class reunion or walked in any Commencement procession but my own. I never joined an alumni group, didnt pitch in to raise money, organize an event, or interview prospective students. I hadnt once submitted a photo or boasted of my achievements in the class books that are published every five years, nor did I buy any of the books and read up on my classmates. See what I mean? I hardly ever thought about Harvardand of course, I protested too much. My partner and coauthor, Jeanne Ellsworth, likes to remind me that I managed to drop it into our very first email exchange and wedge it into the conversation on our first date. So I admit to being proud of it, and I acknowledge that the Harvard imprimatur has opened doors for me. Maybe even hers, she teases.

At the same time, I dont usually make too much of my Harvard degree, and I especially dont want to be associated with the colleges elitist, clubby reputation. Apparently that ambivalence (or false modesty?) is part of it. Malcolm Gladwell says it well when he describes meeting Harvard alums: Dont define me by my school, they seemed to be saying, which implied that their school actually could define them. And it did. Gladwell goes on to describe the reputation that I have always shrunk fromthe backslapping camaraderie, the tales of late nights at the Hasty Pudding, the royal roommates, the houses in the South of France, and the reverence with which the name Harvard is uttered.

In the summer of 2007, I was in my last days as an organic dairy farmer in upstate New York. I made an unlikely farmer for that place: a retirement-age Black man with a Harvard degree and a previous life in network television news. My back-to-the-land moment had come in 1997, when I left NBC News and New York City after almost thirty years as a television news journalist. In 1968, I had started my news career writing, producing, and directing for public televisions groundbreaking Black Journal, an hourlong weekly national news magazine that was for, about, and produced by Blacks. After Black Journal, I traveled throughout the world working for The CBS Evening News with Dan Rather and then NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw. I covered all the wars, real and not so realthe war in Vietnam, the War on Poverty, the war in Grenada, the War on Crime, the War on Drugs, the War on Terrorism. At age fifty-five, I left NBC News, fed up with the rat race, office politics, and the intense commercialization of the news. Farming was hard, but it was good for the soul and the ego. The cows didnt care that I had been a big-time producer and had won three Emmys. They shit on me anyway.

But dairy farming is a young mans game. I was sixty-five, with knees and back wearing out, and I wanted to stop before something incapacitating happened. My marriage of over twenty-five years had also come to an end, and I had no idea where I would go next. One of those bittersweet last days on the farm, I pulled my prized Belarus tractor into the barn after spreading manure on one of the higher hills and clomped down to the mailbox. Among the bills and junk mail I found the latest Harvard Magazine. You might forget about Harvard, but Harvard never, ever forgets about you. I receive relentless pitches for donations and, every two months, my copy of the alumni magazine. Its slick and expensively produced, and it toots the Harvard horn and champions a world where every problem seems on the verge of a solution thanks to some illustrious Harvard grad. The magazine is sent out free of charge to every domestic Harvard alum, and it somehow managed to reach me no matter how much I moved around from house to house, from city to city.

On that morning, as usual, I flipped immediately to the obituary page, and read with sadness that Booker Bradshaw had had a heart attack in his home in Los Angeles and was gone. Booker was a year ahead of me at Harvard, a tall, handsome, light-skinned, popular Black guy. I remembered that after graduation hed gone on to find some fame in Hollywood, and I learned from the obit that he had played somebody called Doctor MBenga in Star Trek on television. Sparked by my coming life changes and the loss of Booker, I found myself wondering what had happened to the Blacks in my class, the class of 1963. Who had done what? Who had been happy? Who had been successful? For that matter, who was still alive? We were all pushing seventy, getting set to leave the planet, and it would be interesting to know what our fellowship and our individual experiences at Harvard had meant to us, how it all looked from fifty years distance.

I spent the following year getting off the farm, selling the cows and equipment, and finding a place to live. The tasks and challenges of reordering my life squeezed out all thoughts about the Harvard project. The next year I met Jeanne via an online dating service, and when we had dinner one evening I told her about my ideas. She was about to retire from university teachingher field was the history of education in the United Statesand she was fascinated by the possibilities. From that first conversation, weve been on this quest. Indeed, we became partners in life and in The Last Negroes at Harvard project.

We would spend the next eight years tracking down and talking to my classmates, starting with no more than a list of names that I pulled from my memory and wrote on a yellow legal pad. I knew where a few of them lived, so I started by getting in touch, and little by little the list took shapecounting me, it totaled eighteen. We eventually found and met with the fourteen who were still living, in person at least once, and most more than once, following up with emails and phone calls. We also talked to some of our white classmates, to Blacks from classes ahead and behind ours, and to relatives of those whod passed away. I interviewed my own father and sister. Jeanne and I drove all around New York and New England, to California twice, and to Georgia, Minnesota, and Michigansome of our best ideas came in the car. And we flew to Austria and St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. Jeanne interviewed me more times than we can count, pulling out stories and feelings that Id never have come up with without her relentless questioning. We spent endless hours transcribing tapes. We talked and read and studied and talked some more as the stories emerged and the ideas for this book slowly took shape. From the very beginning, this was a labor of love for us, and though we did other things over the years, singly and together, this project has been at the center of our lives, the stuff of countless and often contentious conversations. We even joke that once its finished we may have to tackle something else or risk drifting apart.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever»

Look at similar books to The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.