Publishing Director Sarah Lavelle

Copy Editor Lucy Kingett

Editor Susannah Otter

Assistant Editor Stacey Cleworth

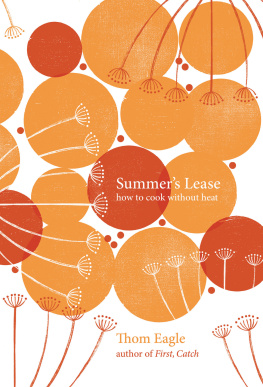

Cover Design and Illustrations Will Webb

Junior Designer Alicia House

Typesetter Jonathan Baker

Head of Production Stephen Lang

Production Controller Nikolaus Ginelli

Published in 2020 by Quadrille, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing

Quadrille

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

quadrille.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Text Thomas Eagle 2020

Design Quadrille 2020

eISBN 9781787135345

CONTENTS

When I think about eating, I think about bread, and when I think about bread, I think about breaking; we break it at every stage of its life. When our ancestors shared food with somebody (which is one way of falling in love) they said they were breaking bread together, and a companion is someone with whom you share that broken bread. Loaves of bread crack and sing as they come from the oven, crusts shifting as they cool on their bent wire racks, and before that, a long time before that, came the pounding and breaking of grain, to smash the seed apart before panning through it like mud in a hopeful river. We have to break if we want to eat, but luckily we love to do so. When scholars of the future come to examine the tragedy of humanity, they may well consider our fatal flaw to lie in this love and in our persistent belief that once we have broken something we can always put it back together again. That we cannot or in other words, that some consequences are permanent is, to my mind, the chief lesson to be gained from the Biblical story of Eden, although the subsequent arrival and sacrifice of Christ complicates the moral somewhat. Classical myths, as is often the case, provide us with clearer lessons.

Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, was picking flowers in a soft meadow in Sicily when the trouble began. As she gathered roses and crocuses and beautiful violets, irises, hyacinths and narcissi, Hades, the king of the underworld, saw her beauty and broke through the hot earth to snatch her away and there the story might have ended. Gods do have a habit of getting their way. Demeter, however, loved her only daughter and, seeing her missing, began to search for her across the face of the earth. She looked across the fertile hills of Sicily and the silted banks of the Nile; she scoured Anatolia and the windy islands, and all across the plains of Greece, and found no sign. No one could give her any word of her daughter. Tired, eventually, and at the end of her tether, Demeter rested, seeking refuge with the Eleusinians in the guise of an elderly woman. Satisfied with the hospitality she received, she gifted the scion of Eleusis with wheat, and helped him scatter it across the earth. At this point, the story leaves the wheat behind and moves on to other things, which is a shame. It would have been good to know what exactly was made of this new grass, stronger and more fruitful than the wild blades that had been previously seen across the plains and the sweeping hills. Presumably it was first boiled whole as a kind of porridge, as Sicilians still do for the Feast of Saint Lucy, a process that requires days of soaking and hours of simmering; eventually somebody must have tried to break the grain, and found that it was good.

Demeter, meanwhile, had discovered the location of her missing daughter and persuaded Zeus to intervene on her behalf. The underworld, however, was governed by suitably inverted laws, including the law of hospitality. Whereas elsewhere to break bread at someones table guaranteed you their protection, in Hades kingdom it made you his prisoner. Demeters daughter knew this, and suffered for her refusal, but had been unable to resist just six seeds of a glistening pomegranate from Hades gloomy orchard. She had thought herself unseen, but kings and gods have spies everywhere. Technically, she should have been lost to the upper land forever, but a deal was struck, and it was agreed that Persephone would spend six months a year as the queen of the underworld and for six months Demeter, goddess of the harvest (she of the grain) would mourn. Even fertile Sicily lies comparatively barren during this time, if you ignore the gleaming groves of orange, lemon, pomelo and indeed pomegranate that still dot the island. Summer and the seasons in general, therefore, were not, to this way of thinking, an essential part of nature or the inexorable consequence of the rhythms of the sun and of the planets, but rather the result of a series of an entirely preventable calamities caused chiefly by lust and by hunger: natural and divine history provide the model for humankind. This being the case, however, the consequences were not only accepted, but celebrated; worshippers of Demeter and Persephone in whatever form did not, to my knowledge, try to liberate the latter from her contract and let the mother reign over an eternal bounty. Persephone goes under every year without fail, and Demeter mourns, and so we have winter; but it is because we have winter that we can have summer. The meaning of summer is that it is fleeting, and so we gorge ourselves upon it, taking everything we can from the season.

The American chef Dan Barber remarks, in the short film On Authenticity, that he wants the cooking in his restaurants to be so seasonal that by the end of a season his chefs are sick of that periods produce. By the end of summer they should be so sick and tired of tomatoes that they cannot wait to see the end of that blushing abundance, so they look forward to the months of squashes and brassicas as they otherwise might to truffles or asparagus, and so on, throughout the year. Only by wringing the utmost from each season, or even each passing day, he seems to be saying, can we really appreciate the next. This is true enough, I suppose, but a glut of peaches does not mean that you have to sit down every day and eat peaches. A large and for most of our history, necessary part of summer cooking has been laying down stores for the winter; taking what can be kept of the season and saving it for the next.

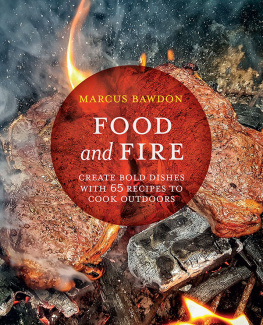

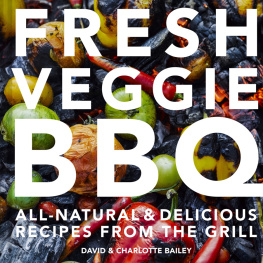

I love the food of summer, but while the heat of summer lasts I do not like to cook in the conventional sense of the word. It seems pleasant, of course, to cook outdoors to smell the smoke of wood and fat drifting across the garden or the courtyard or the beach but the period of the process that involves standing over a hot fire in the hot sun is, in practice, not; as for cooking indoors, the less said about it the better. When I think of the things I miss from the professional kitchen, standing in an enclosed space with the dry heat of an oven on one side, a rolling steam table on the other and a deep-fat fryer in the corner, impregnating your hair with particles of grease, is not something that comes high up on the list. Everything else in the summer kitchen, though, I love. Chunks of ripe and dripping tomatoes, eaten just with salt, leaves crisp from iced water, chopped hard-boiled eggs; dishes that are more arrangements than recipes, of fish or meat or cheese or vegetables, which might be cured or pickled, sliced or whole, but are by and large uncooked: that is to say, they have not been transformed by heat but that is not to say they are