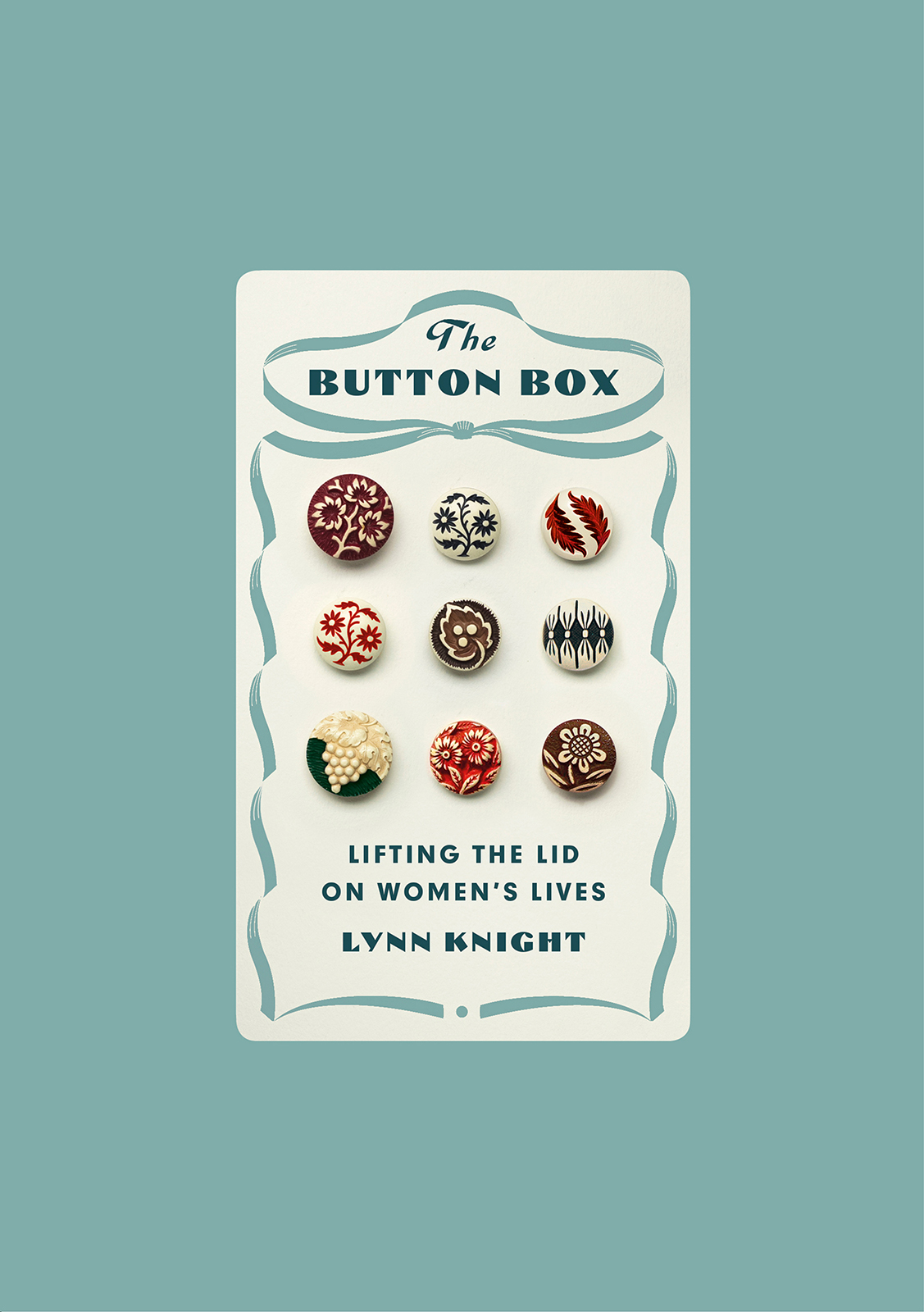

Lynn Knight - The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives

Here you can read online Lynn Knight - The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Random House, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

I used to love the rattle and whoosh of my grandmas buttons as they scattered from their Quality Street tin.

An inlaid wooden box holds the buttons of three generations of women in Lynn Knights family: a scarlet ladybird from her own childhood, chunky turquoise buttons that fastened her mother's sixties-era suit, a sky-blue buckle from a dress her grandmother wore. Each button tells a story.

They change our view of the world and the worlds view of us said Virginia Woolf of clothes. The Button Box explored their role as emblems of security, identity and independence. From the jet button of Victorian mourning, to the short skirts of the 1960s, taking in suffragettes, bachelor girls, little dressmakers and madam shops, Biba and the hankering for vintage, The Button Box examines womens lives with elegance and wit.

Lynn Knight was born in Derbyshire and lives in London. The women of her family, who have passed on many stories along with beaded bags and buttoned gauntlets, fostered her interest in the texture and narratives of womens lives. She is also the author of the biography Clarice Cliff (2005), and a memoir, Lemon Sherbet and Dolly Blue: The Story of an Accidental Family (2011).

Clarice Cliff

Lemon Sherbet and Dolly Blue:

The Story of an Accidental Family

For my mother

I reach into the button box to find the spangled mother-of-pearl criss-crossed with lines and the smaller pearl buttons with serrated edges I remember from my childhood. Here too are workaday reds, blues and greens; flats, domes and globes, diminutive glass flowers and glinting diamants.

I used to love the rattle and whoosh of my grandmas buttons as they scattered from their Quality Street tin, but the tin has done its duty: my own button box is a Victorian writing case with zig-zag bands of marquetry and inlaid mother of pearl. I no longer hear the delicious sound of buttons striking metal but it is still a pleasure to delve for the button whose fish-eye holes, cut diagonally for thread, transform a simple square into diamond-shaped glamour.

As a very small child, I spent Friday afternoons at the house my grandma Annie shared with my great-aunt Eva. The Quality Street tin lodged on a window sill beside the one for Blue Bird Toffees which held my grandmas cotton reels. Buttons stood in for both sweets and currency in the games of shop the three of us played; their kitchen steps were my counter, askew in the pantry doorway. These afternoons also meant Jacobean-print curtains, lemon-scented geraniums and a stained-glass bureau whose individual panes I could trace with my fingertips; there was a rag rug before the hearth and a radio but no television. When my mum came to collect me, straight from town, in her nail polish and belted trench coat, she brought the 1960s into their sitting room.

My grandmas buttons reached back into the past with metal-shanked beauties from the nineteenth century and came forward into my childhood with the pale blue waterlily buttons and ladybirds she stitched on to the clothes she made for me. These buttons now sit among others I have amassed and some of my mothers too. (She, having a mother who at one time sewed for a living, has made it her business to do as little sewing as possible.) I cannot see the buttons without conjuring up the garments they fastened; the eye-popping turquoise buttons from my mums sixties suit so very different in their message from the jet buttons of yesteryear, and the jet buttons themselves, different again from one another, whether fastening ankle-length Edwardian coats that just about swished clear of grimy pavements, or twinkling in a suggestion of upholstered, prickly bodices stiff with beads. I can hardly grasp the tiny buttons that fastened 1920s shoes; no wonder my great-aunt Evas handbags from that time always held a buttonhook. Octagonal buttons recall a trim jacket of hers from the 1940s, that era of morale-boosting suits; a silk-covered button comes from the Chinese-style jacket my mum wore in the late 1950s, while expecting me. A Times leader rightly described button boxes as an epitome of family history.

My grandma Annie was born in 1892, the decade of the New Woman. Times were changing and this working-class girl was photographed standing proudly with the bicycle that took her to grammar school. My great-aunt Eva was born in 1901 on the day of Queen Victorias funeral. Not one for formal lessons, Eva left school as soon as she could and joined my great-grandma Betsy behind the counter of the familys corner shop on the outskirts of Chesterfield, Derbyshire.

My great-grandfathers name was above the door but, like many men in the district, he was engaged in industrial work of one kind or another; the shop was run by my great-grandma. This small shop served a straggle of terraced houses with basic foodstuffs, animal feed and occasional fripperies; linen buttons too, for sewing on to working mens shirts: the majority of customers in this tight small community were the wives of the colliery and foundry men who worked nearby and relied on the shop for groceries and more besides.

There was an Edwardian fastidiousness about my grandma Annie, whereas Eva was as sprightly as the 1920s, the decade when she came of age. My great-aunt was a good playmate when my brother and I were small; if anyone was likely to lead you into mischief it was Eva. More than the many games we played, I remember my delight when, as a teenager in the early 1970s, I discovered clothes my grandma and great-aunt had worn years earlier and had carefully put away: floor-length ribboned nightgowns with lacework bodices, a black silk dress buttoned with tiny glass flowers; a shimmering art-deco scarf. Old was becoming modern and, in some circles at least, vintage was newly chic (though, back in the day, vintage was plain second-hand). The magazines I read, 19 and Honey, showed young women who, when not reclining in Biba-like sophisticated poses, wore crpe-de-Chine frocks set off with little leather handbags or beaded purses like the ones I found upstairs at Annie and Evas. Around this time, my grandmas buttons acquired new meanings. I started raiding her button box for interesting finds to sew on home-made smocks and saw how glac mint buttons and tiny pearl flowers complemented vintage clothes. Further discoveries awaited me in my own home: clothes worn by my mum as a younger woman, including a red tiered chiffon dress that shouted the 1960s.

Even now I can recall the thrill of those discoveries, see the jazzily patterned runner on the upstairs landing in Annie and Evas house, recapture the shiver of silk and the shock of that red chiffon. Many of the clothes have long disappeared but the buttons remain. The button that makes a play on geometry was Annies; best-dressed days saw Eva wearing buttoned gauntlets outlined in caramel-coloured leather my grandma and great-aunt were no different from all the other women wanting to add a touch of glamour to their lives. Writer Jenifer Wayne lovingly recalls a purple dress that signified her becoming a woman; my own equivalent was a crpe-de-Chine suit now remembered by a single button. They change our view of the world and the worlds view of us, said Virginia Woolf of clothes.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives»

Look at similar books to The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Button Box: Lifting the Lid on Womens Lives and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.