PENGUIN BOOKS

LIFTING THE VEIL

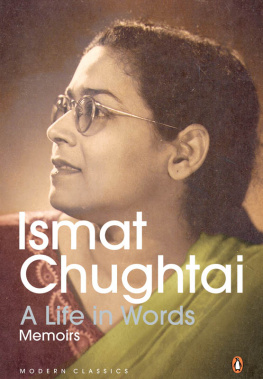

Ismat Chughtai was Urdus most courageous and controversial woman writer of the twentieth century. She was the first Indian Muslim woman to earn both a bachelor of arts and a bachelors in education degree. She began writing in secret due to violent opposition from her family, and many of her works were banned for their fiercely feminist content. Her most celebrated short story, The Quilt, which is included in this publication, was brought to court on charges of obscenity for its suggestion of homosexuality. Ismat Chughtai refused the courts request to apologize for the story, and eventually won the case. She died in 1991.

Kamila Shamsie is the author of seven novels, which have been translated into over 20 languages, including Home Fire (longlisted for the Man Booker Prize), Burnt Shadows (shortlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction) and A God in Every Stone (shortlisted for the Baileys Womens Prize for Fiction). Three of her other novels (In the City by the Sea, Kartography, Broken Verses) have received awards from the Pakistan Academy of Letters. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and one of Grantas Best of Young British Novelists, she grew up in Karachi, and now lives in London.

M. Asaduddin translates Assamese, Bengali, Urdu, Hindi and English. He writes on the art of translation and fiction in Indian languages. He has recently edited For Freedoms Sake: Stories and Sketches of Saadat Hasan Manto (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2001) and edited with Mushirul Hasan Image and Representation: Studies of Muslim Lives in India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000). A former fellow at the British Centre for Literary Translation, University of East Anglia, UK, he currently teaches English literature and Translation Studies at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.

HELL-BOUND

The first part of this piece is extracted from a brief autobiographical essay, included here because it forms a good introduction to the rest.

Ismat Chughtai

LIFTING THE VEIL

Selected and translated by M. Asaduddin

With an introduction by Kamila Shamsie

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in India by Penguin Books India 2001

First published with a new introduction in Great Britain by Penguin Books 2018

Text copyright Ashish Sawhny, 2001

Introduction copyright Kamila Shamsie, 2018

In the Name of Those Married Women first appeared in Ismat: Her Life, Her Times Katha 2000

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted

Cover illustration Martha Rich

ISBN: 978-0-241-34644-0

For Nasreen who has crossed many barriers

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure for me to acknowledge my debt to the following who helped me generously at different stages of the work: G. J. V. Prasad for agreeing to edit the manuscript despite his other pressing commitments; Karthika and Diya at Penguin for being very supportive; Moazzam Sheikh and S. M. Mirza for reading some of the translations; Ralph Russell for allowing me to use his translations; and, finally, to Zubin, for many distractions.

Introduction

Perhaps my mind is not an artists brush but an ordinary camera that records reality as it is. So the pioneering Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai wrote in the essay In the Name of Those Married Women, which is included in this gloriously provocative collection of short stories and non-fiction. Its possible to view that line as a modest utterance, or one that reveals the not uncommon discomfort among women to claim the mantle of artist for themselves. But Chughtais words often carry a sting, and so it is here and not only because of that equivocating perhaps. The essay was her response to the controversy ignited by her short story The Quilt, published in 1942, which landed her in court under obscenity charges for its depictions of lesbian sex. In claiming to be an ordinary camera that records reality Chughtai was reminding both her readers, and the man with whom she was directly arguing, that everything she writes about is all around us its merely hypocritical to pretend otherwise. Elsewhere in the essay she went further to pinpoint peoples discomfort with the story in order to reveal a further hypocrisy the gender of the writer caused more scandal than the gender of the two lovers under the quilt.

Read today, The Quilt raises eyebrows for different reasons. In it, the unhappily married Begum (unhappy because her husband is gay and has a string of lovers to entertain him while she is neglected) turns to another woman out of frustration rather than as a genuine expression of desire. But at the heart of the story is Chughtais insistence that female sexuality is as potent and powerful as male desire. Female sexuality within a patriarchal world is Chughtais central concern through many of her stories: in The Homemaker a woman who enjoys the power of her sexuality tries to resist marriage to the man whom she really loves, knowing it will ruin their relationship; in The Net two young girls find their friendship pulled apart when an awareness of sensuality enters their lives via a silken garment; in Kafir a Hindu boy and Muslim girl grow up together with desire pulling them one way and social norms pulling them the other. But whether she is writing of womens sexuality, or of an Englishman who tries to make India his home after the end of empire, although neither the Indians nor the English want him to do it (in Quit India), or of an ageing man who is tormented by his own diminishing potency (in The Invalid), Chughtai always has the most acute eye for human psychology married to a refusal to shy away from any topic that interests her. I think the first word articulated by me after birth was why, she wrote in her memoir.

Perhaps the most moving piece in here is My Friend, My Enemy!, the non-fiction account of her relationship with the Urdu short-story writer Saadat Hasan Manto. Their shared friendship extended to sharing the dock in court they were charged together for obscenity, she for The Quilt and he for his story Bu and it made the bond between them very strong, though Partition physically moved them apart: Manto went to Pakistan, while Chughtai stayed in India. Here is Chughtai describing their first meeting: In a few moments we began to argue vociferously. It was as though we had suffered a great loss from not having met each other for a long time and were now impatient to make good the loss. Let other writers write of like-mindedness; in the world of Ismat Chughtai, human nature is never so neat. People are drawn to each other simply because they are and then begins the difficult, joyous, messy business of being human together.

Kamila Shamsie

Gainda

This is our shack, Gainda and I told ourselves as we crawled into the dense shrubbery. Sitting on our haunches, we began to tidy up the ground with both hands. In a little while we were squatting on the smooth floor of the shack without a care in the world. After a brief tte--tte we began to play our favourite game dulhan-dulhan. Gainda drew her smelly red dupatta over her face and sat huddled like a real bride. I lifted the veil gently and had a glimpse of her. Gaindas round face turned crimson as a fresh wave of blood coursed through her veins. Her eyelids fluttered uncontrollably, and she could barely stop herself from bursting into laughter.