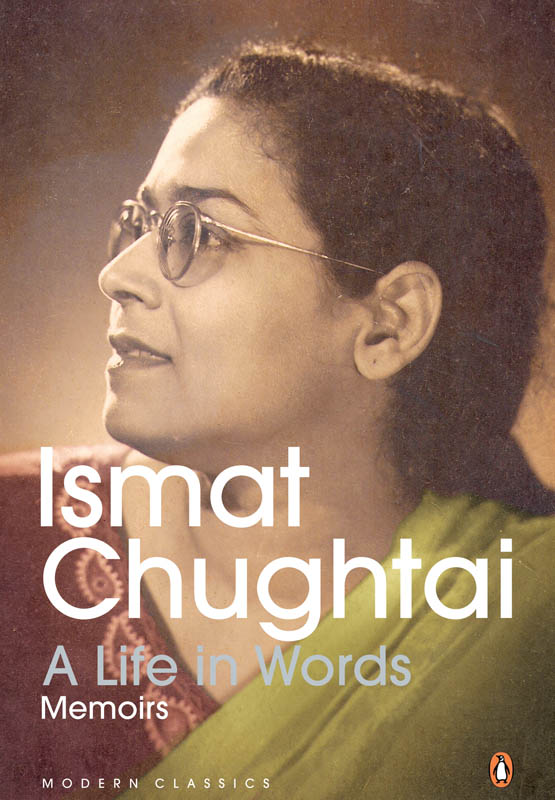

Ismat Chughtai (191191) was Urdus most courageous and controversial woman writer in the twentieth century. She carved a niche for herself among her contemporaries of Urdu fiction writersRajinder Singh Bedi, Saadat Hasan Manto and Krishan Chanderby introducing areas of experience not explored before. Her work not only transformed the complexion of Urdu fiction but also brought about an attitudinal change in the assessment of literary works. Although a spirited member of the Progressive Writers Movement in India, she spoke vehemently against its orthodoxy and inflexibility. Often perceived as a feminist writer, Chughtai explored female sexuality while also exploring other dimensions of social and existential reality.

M. Asaduddin is an author, critic and translator. His work has been recognized with the Sahitya Akademi Prize, and the Katha and A.K. Ramanujan awards for translation. Among the books he has published are The Penguin Book of Classic Urdu Stories, Lifting the Veil: Selected Writings of Ismat Chughtai, For Freedoms Sake: Manto, Joseph Conrad: Between Culture and Colonialism, and (with Mushirul Hasan) Image and Representation: Stories of Muslim Lives in India. He is currently Professor, Department of English, Jamia Millia Islamia.

Praise for the Book

Translator M. Asaduddin has... done a remarkable job, catching all the nuances of Chughtais luscious prose and extraordinary wit. This is a book for all to read and enjoyHindustan Times

Ismat Chughtais candid words continue to be contemporary and cutting edgeThe Hindu

Asaduddins work is top-of-the-shelf stuff... it transports you to the world of the original... If you have not read Chughtai before, this will whet your appetiteOutlook

A youthful Ismat Chughtai jumps exuberantly from every page, outrageously outspoken, courageous, honest and very, very funny... there is never a dull momentIndian Express

These essays showcase the best of Chughtais range and mastery as a writerthey are erudite, self-aware and always probing... [Asaduddins] work is nimble and nuancedTime Out

Ismat Chughtais memoir is a reader-friendly, breezy, almost racy readMail Today

The first complete translation of celebrated Urdu writer Ismat Chughtais Kaghazi Hai Pairahan is a delightful and authentic account of several years of her lifeSunday Standard

Ismats vivid descriptive style, her rich imagery, her wry humour and a rare ability to look critically at herself, all come together to etch an interesting canvas of an era gone by... a must-read for every modern, thinking, liberal Indian woman... This book is a compulsive page-turnerBusiness Line

Breezy and engagingBusiness Standard

The book... has several gems in the sketches and descriptions... And it owes as much to Asaduddin as Chughtai that this is soFinancial Express

The first thing one notices on starting the short story writer, feminist, educationalist and iconoclast Ismat Chughtais remarkable memoirs, A Life in Words: Memoirs, with due credit to M. Asaduddins elegant translation, is how utterly unselfconscious, unaffected and natural the writing seemsMint

This is a fantastic work, so detailed, so sincere, so intensely humanFree Press Journal

A must-read for anyone interested in literature, or for that matter, lifeReading Room

An honest and brilliant description of Ismat Chughtais life and timesNew Woman

[Chughtais] memoirs are just as radical as her fictionDNA

Eminently readable... superbly translatedReading Hour

For

Shamim Hanfi

my Urdu mentor

ISMAT CHUGHTAI

A Life in Words

MEMOIRS

Translated from the original Urdu Kaghazi Hai Pairahan

by M. Asaduddin

Introduction

Ismat Chughtai (191191)lobbied relentlesslyand successfullyto get an education, struggled fiercely to find her own voice and wrote with passion and panache to depict the visible and subtle tyrannies of contemporary society and her conflicts with the values that made them possible.

Kaghazi Hai Pairahan (henceforth, KHP), generally known to be Ismat Chughtais autobiography, is a curious piece of work. It is certainly written by Ismat Chughtai, and it is about her life, her family and her growth and development as a writer. But it is not a straightforward autobiography inasmuch as it does not record the authors life storyfrom her birth to the point of writing the bookin a chronological order. It is fragmented, jagged, written in fits and starts when spurts of memory propelled her to record her reminiscences, without consideration for chronology, repetition or narrative coherence. Perhaps it is not realistic to expect a traditional autobiography from such an individualistic, temperamental and radical writer like Ismat Chughtai, who never moved on a straight or predictable path, much like the heroine, Shaman, of her autobiographical novel, Terhi Lakeer (Crooked Line).

The fourteen chapters of KHP, written for the Urdu journal Aaj Kal, were published from March 1979 to May 1980. The general tenor of the chapters and the manner in which they were written is illustrated by the following note from the author to the editor of Aaj Kal when she sent in the second instalment:

Im sending the second chapter. I am trying to record from my memory the events that affected me and what I had heard from conversations in the family, the tensions inherent in every class, new questions and their resolutionall this is so complicated. I will send you whatever gets written at any point of time. Let them be published under different titles. The sequence might be worked out while editing them [for the volume].

The writer did not have the opportunity to take a second look, much less edit what she had written because of other preoccupations

The span of the volume is limited to the years between when Ismat Chughtai entered high school to the time of writing her controversial story, Lihaaf. In other words, the autobiography records the events of only a couple of years of her life. Even with the addition of the opening chapter there are silences and gaps that cry out to be verbalized and filled up. However, within this limited timeframe, we find encapsulated vignettes that point to the multiple and richly tapestried cultural matrix that went into developing Ismat Chughtais artistic sensibility.

The real absence in KHP is any vignette from her married life, even though her husband, Shahid Lateef, figures in many places. One gets just a fleeting glimpse in the chapter, In the Name of Those Married Women... It is a matter of speculation as to why a brutally honest These questions will tantalize readers as they go through the pages of this volume.