Contents

Page List

Guide

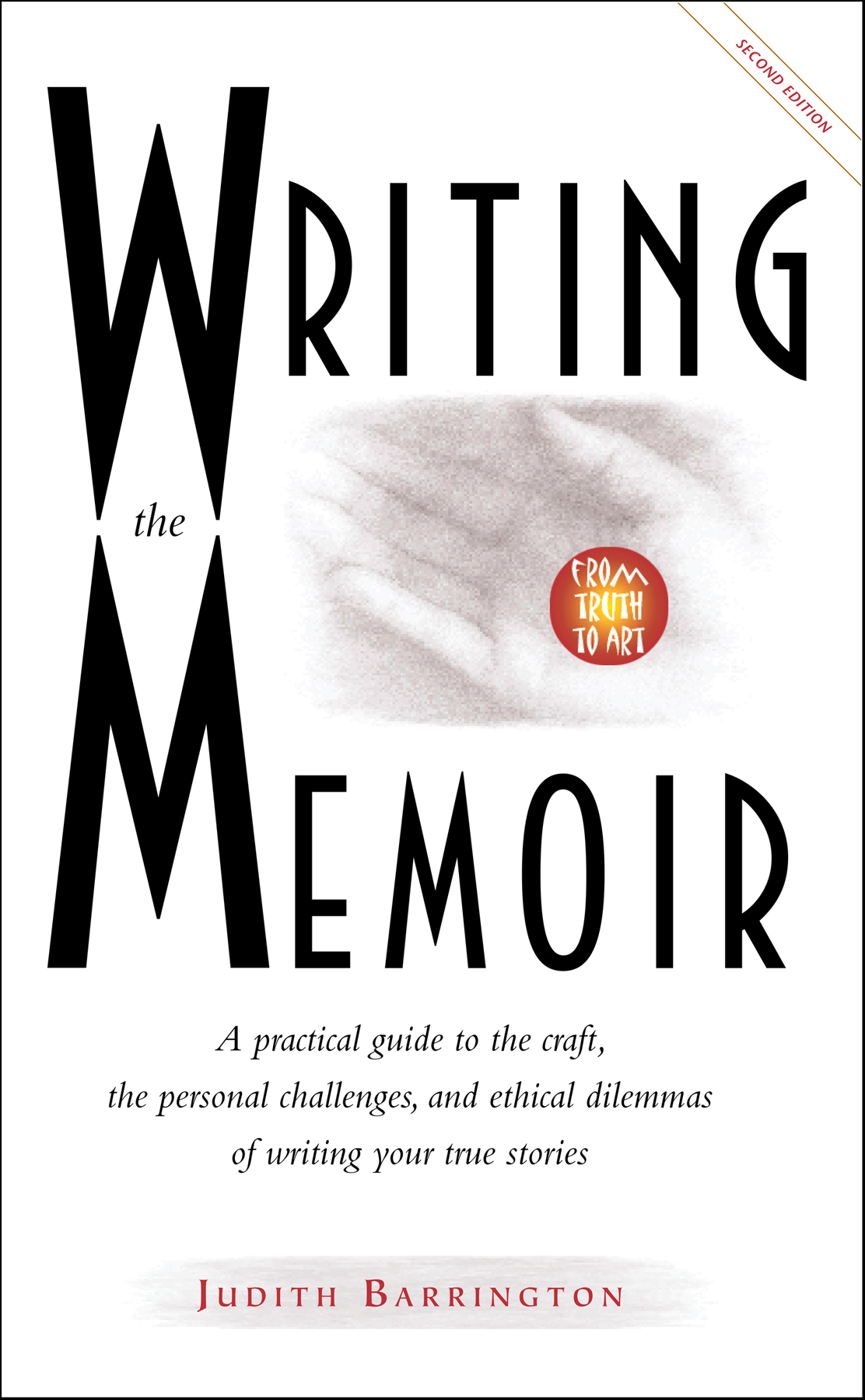

WRITING

the

MEMOIR

Second Edition

JUDITH BARRINGTON

The Eighth Mountain Press

Portland, Oregon 2002

ISBN 978-0-933377-54-7

Also by Judith Barrington

Poetry

TRYING TO BE AN HONEST WOMAN

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY

HORSES AND THE HUMAN SOUL

THE CONVERSATION

LONG LOVE:

New and Selected Poems 1985 2017

Nonfiction

LIFESAVING: A MEMOIR

Table of Contents

Introduction

On March 4th, 1920, Virginia Woolf attended the first meeting of the Memoir Club, a group convened by Molly McCarthy. There were about a dozen of themall old friends and members of what we now call the Bloomsbury Groupand one of their stated goals was absolute frankness. At that first meeting, two women, McCarthy and Woolfs sister, Vanessa, and three men including vanessas husband, Clive Bell, read autobiographical essays aloud to the assembled company. At the second meeting, Woolf read 22 Hyde Park Gate, a shockingly revealing memoir about her half brother George Duckworths incestuous relationship with her and her sister (published much later in Moments of Being). She reported in her diary that the experience left her most unpleasantly discomfited. I couldnt help figuring, she wrote, a kind of uncomfortable boredom on the part of the males, to whose genial cheerful sense my revelations were at once mawkish and distasteful. What possessed me to lay bare my soul!

Now, with a reading audience hungry for personal narratives, memoirs are appearing in ever greater numbers. But laying bare the soul with absolute frankness is still an act of courage for women and for men too, though for somewhat different reasons. Men, even today, are not supposed to be preoccupied with soul searching: to be honest about their inner lives and their relationships is still uncomfortably close to transgressing the male role. For women, deeply personal writing can also be described as a rebellion against the expected role, though in the case of women, the expectation is that we will be preoccupied with inner lives, with relationships, and with family, but that we will gear our stories to satisfy, flatter, or collude with our immediate circle.

As soon as I started to write about my own life, I understood that to speak honestly about family and community is to step way out of line, to risk accusations of betrayal, and to shoulder the burden of being the one who blows the whistle on the myths that families and communities create to protect themselves from painful truths. This threat was like a great shadow lurking at the corner of my vision, as it is for anyone who approaches this task, even before the writing leads them into sticky territory.

I was moulded into a pursuer of truth by my times. Active in the early feminist movement and shaped by the consciousness-raising that insisted on scrupulously examined lives, I was challenged in my twenties to take a second look, and then a third and fourth one, at the facts of my life. I was inspired by pioneers like Woolf and, over the years, cherished the increasing number of memoirs written by a wide range of womenwomen of color and white women, heterosexual women and lesbiansand also by men of good will. I was able to witness how the social movements we created, movements whose members had previously been marginalized or invisible in literature, brought about radical changes in both our determination to tell our stories and in our access to publishing. This flowering of voices paved the way for more and more people to tell their stories, whether or not they participated in these movements or felt personally impacted by social change.

My own route to memoir was via poetry. Although the rhythms and images of poems were often what led me into the stories I wanted to tell, more and more I found myself needing the expansiveness of prose to explore them further, even after I had shaped them into verse. Since I couldnt always remember the facts surrounding an event, I found myself making up certain details and embellishing the story whose essence demanded that I give it form. For a while I was confused about this: did it mean I ought to be writing fiction? How much could I really make up? Could I trust my memory at all? What were the rules of memoir anyway?

I could find little to help me as I considered these questions. Once in a while I would have a conversation with a writer friend about truth and memory; occasionally I would debate the boundaries of fiction and memoir with a fiction writer. I read as many memoirs as I could get my hands on, noticing the memoirs surprising ability to adapt its form in the hands of different authors and in the service of varying subjects. I puzzled over its relationship to the more formal essays I had learned to write in school and wondered whether I should be polishing up those old techniques or trying to forget them.

This book, then, is the kind of book I once looked for but was never able to find. It opens up the conversations about memoir I wish Id had when I was starting out and addresses the nuts-and-bolts questions that pertain to the memoir genre, as well as some others that apply more generally to prose writing. Having now taught the memoir for many years, I also offer a few linguistic and grammatical definitions that many of my students who are excellent writers missed out on along the way.

In the five years since Writing the Memoir was published, I have read a good many new memoirssome disappointing, a few splendidly memorable, and many in betweenand I welcome the opportunity to refer to some of these books in this new edition. I have also, during this time, continued to teach classes and workshops on the memoir. My students, in addition to producing some brilliant responses to the Suggestions for Writing, have identified their most pressing concerns. I have therefore expanded some sections to discuss more fully the issues of both craft and responsibility which they raise most frequently and discuss most passionately.

I hope this book will encourage all of you who are drawn to tell your own stories, for I think this is very important work. For members of marginalized groups, speaking personally and truthfully about our lives plays a small part in erasing years of invisibility and interpretation by others. And for all of us, engaging seriously with the truth challenges our societys enormous untruthfulnesswhether it comes from the family, which so often denies its own violence behind closed doors, or from the national and international powers that deny their own violence and call it peace keeping.

To write honestly about our lives requires that we work at and refine our artistic skills so that our memoirs can effectively communicate the hard-won, deep layers of truth that are rarely part of conventional social discourse. It requires, too, that we grapple with all the ethical questions that arise when we shun commonly accepted definitions of loyalty: questions like can I really tell that story or will it hurt my mother? By demanding our loyalty in the form of silence, some of the people we are closest to have coerced us into collaborating with lies or myths. We cannot, however, respond to this coercion by rushing angrily into print. We must examine our responsibility as writers to those we write about, even while holding fast to our truths.

In this book, I assume that the reader aspires to the highest literary standards, and I provide tools that I hope will be helpful to the serious creative writer. However, I trust it may also encourage and assist the many who are not yet, or may never be, thinking in terms of publication.