Published by Bucknell University Press

Copublished by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

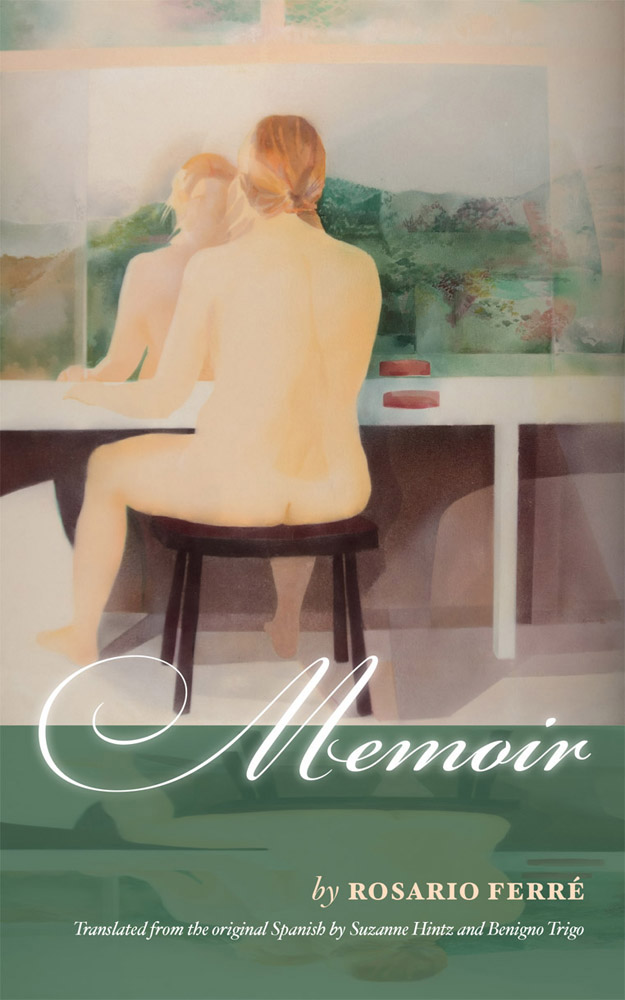

Copyright 2016 by Rosario Ferr

Original title: Memoria

Copyright 2011 by Universidad Vercruzana

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN: 978-1-61148-662-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-1-61148-663-6 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For my son Benigno,

traveling companion

across the landscape

of memory

Prologue

Storytelling is a living consciousness:

knowing who you are, what is within you, and what you can do.

SCHEHEREZADE

The myrtle is a flower that blooms; after the rain, its perfume attracts ghosts. When I married and went to the capital city to live, Mother sent me some myrtle bushes from the patio of our house in La Alhambra. Our chauffeur Carmelo Bocachica brought them to me planted in Yaucono coffee cans. Those myrtle bushes were originally from the garden in Guanajibo and Mother had transplanted them to her garden in Ponce when she married and moved there to live. Mother told me that I should plant the bushes under my balcony so that I could enjoy their perfume at night, especially after it rained.

From childhood I realized that Mother did not like public life. The 1930s and 1940s were extremely difficult years, the dreadful decades of Puerto Rican history. Father soon became convinced that only through political action would he be able to help other Puerto Ricans. Nevertheless, for Mother politics were always tales of sound and fury. She used to make fun of the statues of our founding fathers, facing a future so unhygienic as having ones head eternally shat upon by birds. When town leaders came to the Alhambra house heavy with presents like laying chickens with shiny feathers, baskets full of Nebo oranges, bananas or big pineapples, or when they sent ice boxes stuffed with red snappers, dog snappers and hogfish, Mother would thank them with a sad smile whose meaning only I understood. Those fruits of the land and the sea that they brought to her husband meant only one thing to her: one day Father would no longer belong to her. She would have to share him with everyone. And what was worse, she would stop belonging to her own self. She would lose her personal space forever, her right to silence and to walk on the sunny side of the street without being pointed out or recognized by anyone. What happened to her was what the members of certain tribes believe happens when someone captures their image. Their spirit no longer swims free and anonymous in the powerful current of universal energy. The spirit becomes part of history and its cultural patrimony.

Mother became gravely ill shortly after Fathers successful run for governor of the Island in 1968. She understood that the end of her life was near. She did not want an elaborate funeral with public rites traditionally given to a leaders wife. She asked that her funeral be the simplest possible and that no one send flowers. She asked Father to make an announcement in the newspaper to that effect so that people would donate money anonymously to charitable causes. She has no pantheon with a roof. Scoured by the rain, sun, and wind, her simple tomb in the capitals cemetery today honors her preferences. Her tomb does not have a cross, bust, figure of a crying angel, nor a bleeding sacred heart that interrupts the white sobriety of its lines. It is for that reason that I dedicate this memoir to her.

The Word Became Flesh

I suppose that the literary vein comes to me from my mothers side. My maternal grandmother had a literary imagination that was out of control, as one can see by the names she gave to some of her daughters: Fredeswinda, Wagnerian valkyrie; Olga Act, Russian czarina; Zorhaida, Cervantine heroine from his Novelas Ejemplares. I adored my eight maternal aunts. Aunt Hayde (Yiyi) and Aunt Olga were poets. They recited poetry during our Christmas dinners at the Guanajibo house, outside the city of Mayagez. Yiyi had a natural talent for poetry. She was known for her poetry since her high school years in San Germn. There she won the beautifully provincial title of Princess of Poetry during a literary contest recital at the Mayagez Athaneum. Later she earned recognition from the intellectual community when she earned her bachelors degree at Ro Piedras, where she met the Spanish poet Juan Ramn Jimnez. She published a beautiful book, entitled Poesa, with his support. My aunt was married to a Republican from the Spanish Civil War who had arrived in Puerto Rico as a refugee. My uncle was a gastroenterologist. He had in his office one of the first colonoscopes on the Island, and he taught at the University of Puerto Rico (UPR). Aunt Yiyi married him; and the Nightingale, as she was known, put aside her poetry. Aunt Olga, who also had poetic talent, married a brilliant botanist, an expert in phytopathology. She shut herself up in Cerro Las Mesas to write postmodern poetry, a style that fit her sweet and innocent personality well.

From the time I was little, I wanted to be just like them, to be able to write and recite beautiful poetry but not to remain anonymous. I wanted to make writing my profession. My aunts spoke of a womans world and they tried to interpret it. It was a way to look at the world that allowed them both to be useful and to transcend life, thanks to its spiritual values. My aunts work was behind the scenes, eternal Penelopes who devotedly followed their husbands orders.

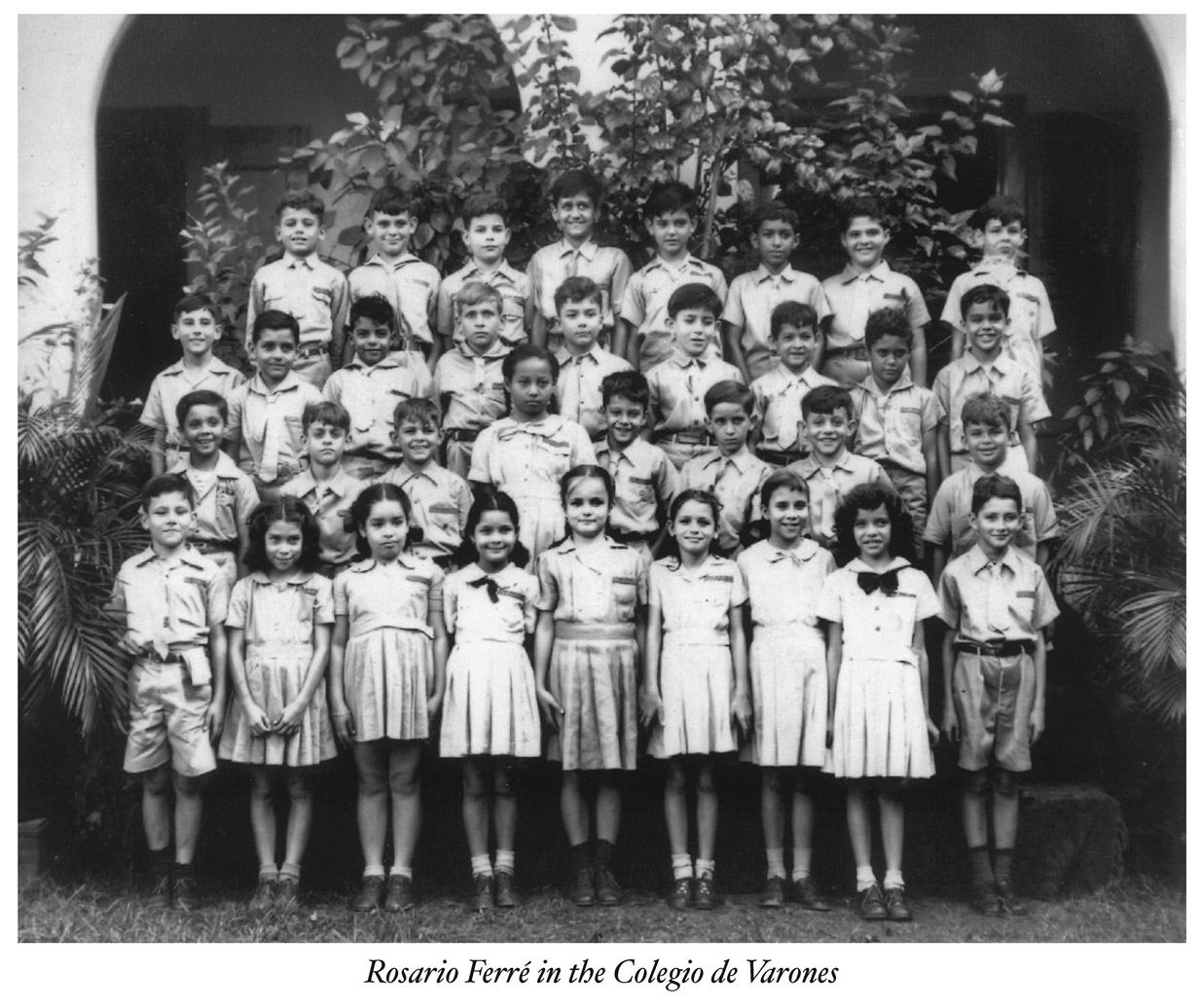

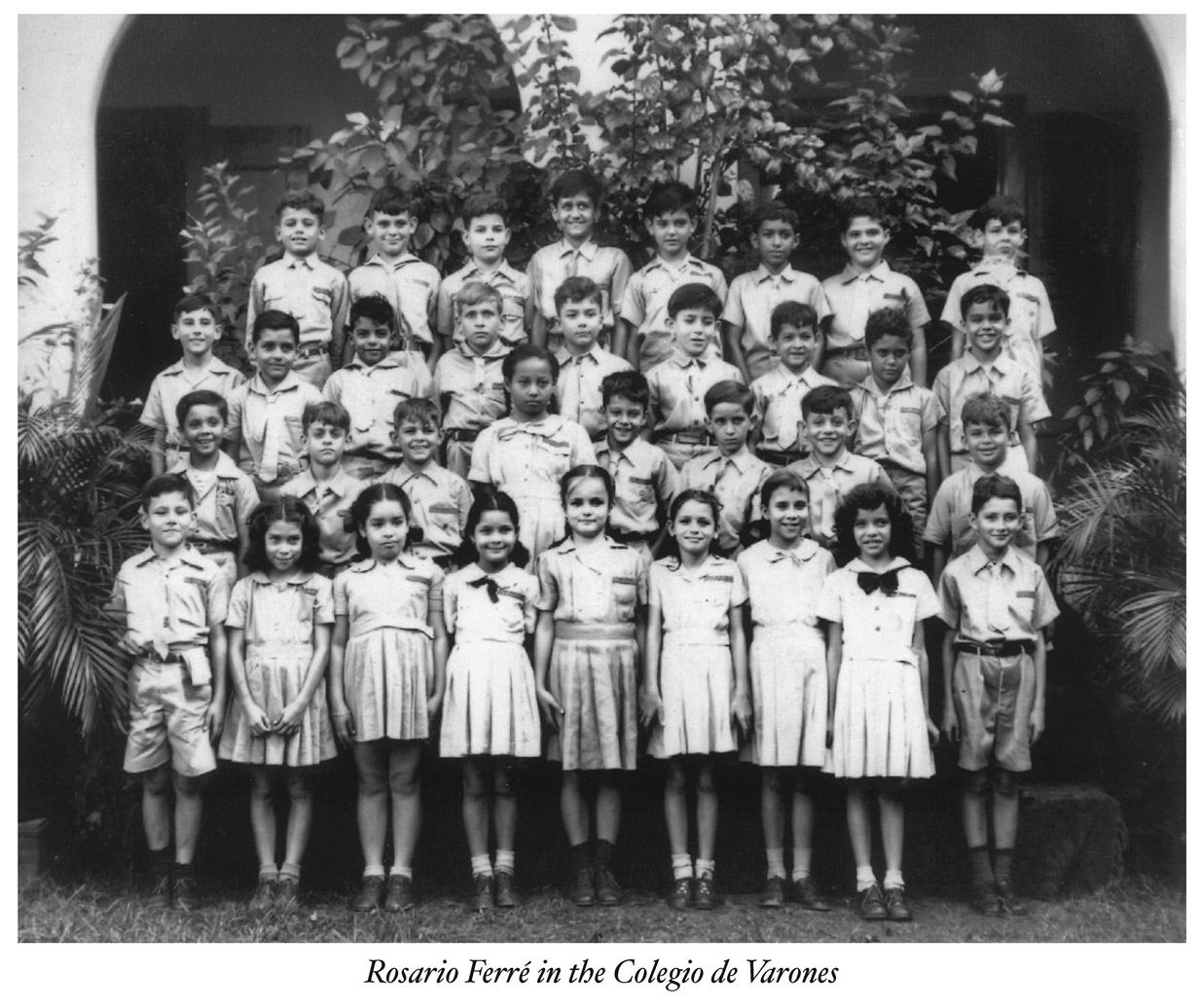

When I was six years old, my parents enrolled me in the Colegio de Varones in Ponce, an elementary school that was mixed boys and girls until the fourth grade. I was completely happy there and never felt that anyone discriminated against me for being left-handed and female. The Marianist fathers were American and had an advanced educational philosophy for their time. But I experienced discrimination later, when I changed elementary schools. When I began fifth grade, my parents moved me to the Colegio del Sagrado Corazn, an institution still set deep in the Middle Ages. At that time Sagrado Corazn was an elitist institution charged with educating young girls from the upper class. Thus, all the students in the school were white and wrote with their right hands. Everyone knew that left-handers went to hell! Today its completely different. Sagrado Corazn in Ponce closed some years later. It returned as an institution completely dedicated to social causes, and it did a world of good.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.