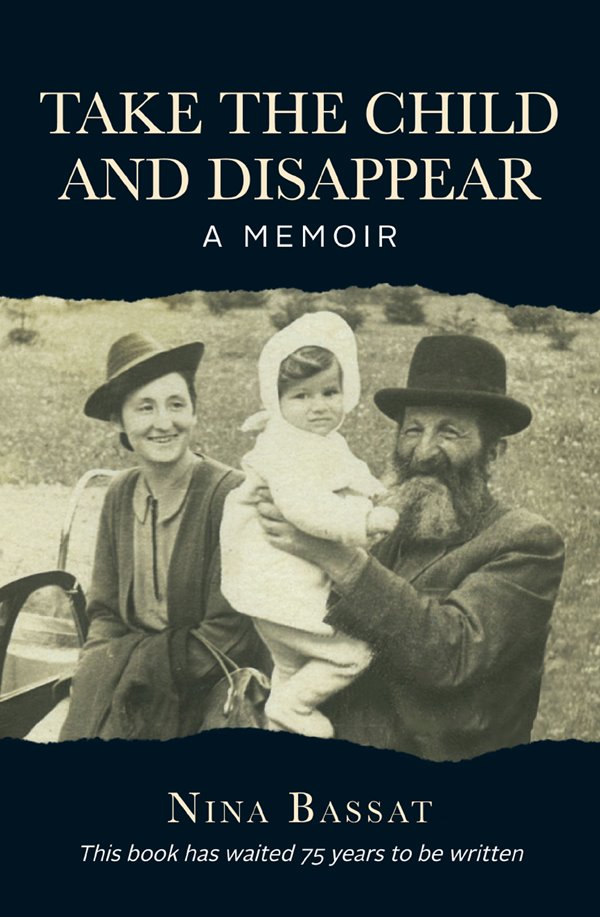

Take the Child and Disappear

Nina Bassat was born in Lww, Poland in 1939. The time and place have influenced much of her life and provide the background to her book Take the Child and Disappear. Her life has been divided between her profession as a lawyer, her leadership positions in the Jewish community at the state, federal and international levels and her family, which has been her centre of gravity. Since her childhood, books have been both a joy and escape, and words have been her professional tools.

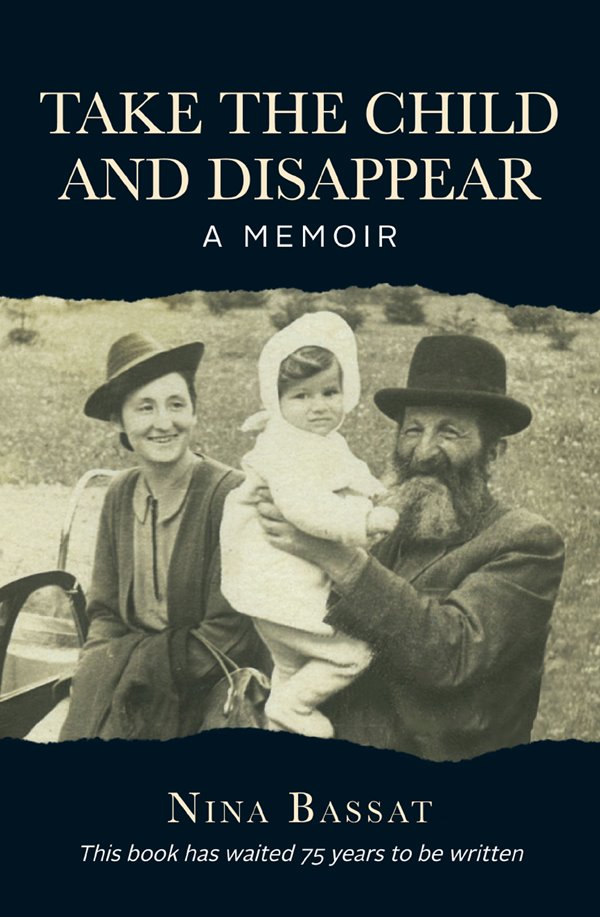

This book has waited 75 years to be written.

Praise for Take the Child and Disappear

In her poignantly enthralling memoir, Nina Bassat tells us that Childhood memory is a gossamer thing. The born writer in her, however, shows us that memory can carry so much more weight than gossamer. In Take the Child and Disappear it carries the heavy burden of Zachor, the Jewish command to remember and relive. When the author, who survived the Shoah in the Lww Ghetto, returns some seven decades later to her mothers shtetl birthplace and family home in Polands Jdrzejw, her journey is a moving Kaddish for what was lost so brutally and murderously. But in returning, she not only honours and memorialises the dead; she is a defiant retrospective eyewitness to history, and declares victory for the living Jewish people which and this is her storys ultimate triumph she has served with such distinction in Australia and internationally.

Sam Lipski AO, formerly Editor-in-Chief Australian Jewish News, and founding publisher of The Jerusalem Report

Graceful, dignified and full of heart, Take The Child And Disappear is not only a story of child survival unlike any Ive heard, but also a love letter to a remarkable mother and a tale of triumph in a new land. With great clarity, Nina Bassat has gifted us an inspirational addition to the patchwork of Holocaust and Jewish Australian history.

Bram Presser, author of The Book of Dirt

This is a profoundly moving, beautifully written account of a childs experience of the struggle for survival during the horrors of the Holocaust, interspersed with deep reflections on its impact on her life, from Nina Bassat, who became a leading figure in Australian Jewry. Compulsory reading for anyone wishing to understand the realities of the Holocaust, Jewish survivor resilience and Australian Jewry.

Suzanne D. Rutland OAM, Professor Emerita,

University of Sydney

Published by Hybrid Publishers

Melbourne Victoria Australia

Nina Bassat 2021

This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to the Publisher, Hybrid Publishers, PO Box 52, Ormond, Victoria, Australia 3204.

www.hybridpublishers.com.au

First published 2021

ISBN: 9781925736724 (p)

9781925736731 (e)

Cover design: Gittus Graphics, www.gggraphics.com.au

Front cover photo of Nina Bassat with her mother and grandfather in 1941 from the authors collection

Contents

Chapter 1

Jdrzejw 2012

The return trip to Jdrzejw took sixty-six years, almost to the day. Jdrzejw is a small, rather ordinary town with no outstanding features and, if nothing else, its unpronounceable name makes it an unlikely destination for tourists. And yet this was a journey I had to make, even though I could not fully articulate the reasons.

The pretext was the reclamation by our family, through a lengthy legal process, of my grandparents property and the important decisions which subsequently had to be made. Probably these matters could have been dealt with from a distance and did not justify what I knew would be a painful experience. And yet, I needed to go. Jdrzejw was my mother Hadassas birthplace, and briefly our home, in the aftermath of the Shoah, the Holocaust. In my mind, it is forever the epitome of what had been lost.

Little did I know just how much had been lost. Two things struck me. The first was how small and neglected the town appeared and the second was that there was no vestige of Jewish life. Where were the butchers, the cheders, the cemetery, the shuls, the mezuzzot on the doors? There was no reminder of the decades of rich Jewish culture, no reminder of what was if not a warm, at the least a civilised relationship, with their non-Jewish neighbours. I could feel no connection, no sense of belonging to what was around me only a huge emptiness. My history, both personal and that of all Jdrzejw Jews, had disappeared. There was nothing but a sharp awareness of the void and of the loneliness. I was here; but where were all the other people who belonged here with me? Obliterated; all obliterated.

In Jdrzejw, which before the war had a significant Jewish presence, where my grandfather Moshe Wargo made his mark as a city councillor, there was no sign, no whisper of a Jewish existence. There, said our Polish companion, pointing down a narrow street, thats where the ghetto was. How could that be? This was just an ordinary narrow street. This could not possibly be the place where the Jews of Jdrzejw were herded, where they suffered and were humiliated, and from where they had ultimately been taken to their deaths at Treblinka.

And then it became clear why I had to come back. It was to re-establish, in whatever small way possible, the existence here of Jews. To create a footprint, however minute, that said we were once here and our presence mattered.

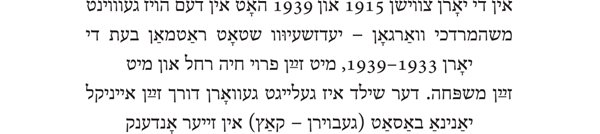

For complicated reasons, and much against my daughters and my own will, our family property had to be sold. I needed to see my mothers house while we still owned it. I needed to walk in the yard where I once had played and to say to myself, Jews once again own this property. The sale was emotionally wrenching but made somewhat less so by my insistence, once I arrived and saw the complete desolation of Jewish life, that a clause in the contract ensured that a plaque would be affixed in perpetuity to the building of my grandparents home. And thus, even though I had already returned to Melbourne by the time the plaque was in place, in 2012 in Jdrzejw the Yiddish language finally made its reappearance, albeit in a very minor way. This was not merely an assertion of our presence. It was an assertion of the triumph of our survival.

There is now a plaque on the building at what once was ulica (street) Klasztorna No. 9-11 and is now ulica 11 Listopada No. 15, which says in Polish and Yiddish:

W tym domu w latach 19151939 mieszka wraz z ona Chaj Ruchl oraz rodzin Moszek Mordka Wargo radny miasta Jdrzejowa w latach 193339.

Dla uczezenia ich pamici tablic ufundowaa wnuczka Janina Bassat (z domu Katz)

This translates to: Moszek Mordka Wargo, Councillor of Jdrzejw from 19331939 lived in this house together with his wife Chaja Ruchla and his family in the years 1915 to 1939. In memory of the above, this plaque was laid by their granddaughter Janina Bassat (ne Katz).