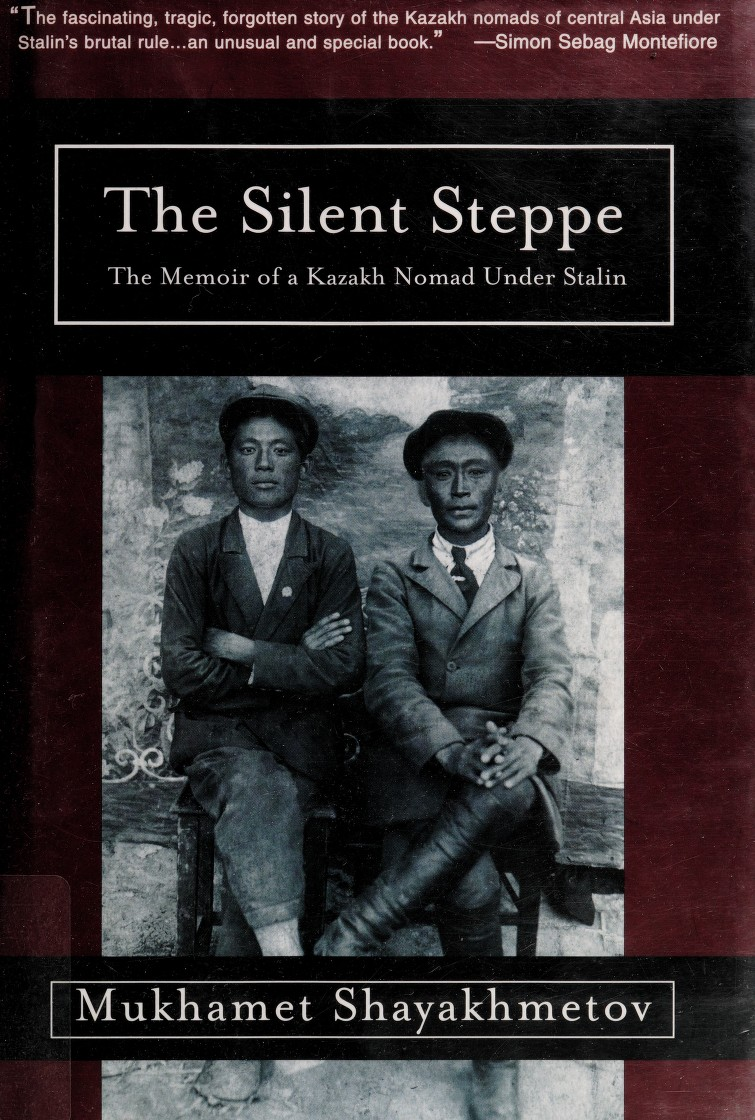

The Silent Steppe: The Memoir of a Kazakh Nomad Under Stalin

CONTENTS

Introduction by Tom Stacey

Prologue: The Fugitive

PART ONE: Class Enemy

Chapter 1: The Life We Lost

Chapter 2: My Uncles Trial

Chapter 3: The Holy Yurt

Chapter 4: My Sisters Secret Wedding

Chapter 3: The Last Autumn of the Nomadic Aul

Chapter 6: The Escape of the Oralman Clans

Chapter 7: School

Chapter 8: The Kulaks Son

Chapter 9: Confiscation

Chapter 10: The Silent Steppe

Chapter 11: Leaving Much-Loved Places

Chapter 12: My Perilous Journey

Chapter 13: At Kalmakbai Aul2

Chapter 14: Deportation

PART TWO: Famine

Chapter 15: The Refugees

Chapter 16: Fleeing Back Home

Chapter 17: Hunger Comes to the Aul

Chapter 18: Days of Mourning

Chapter 19: The New Harvest

Chapter 20: The Milk of Human Kindness

Chapter 21: The Last Days of Famine

Chapter 22: A Home of our Own

Chapter 23: Adolescence

PART THREE: War

Chapter 24: The Coming of the Great Patriotic War

Chapter 25: In the Red Army

Chapter 26: At the Front

Chapter 27: Stalingrad

Chapter 28: Casualty

Chapter 29: On the Border

Chapter 30: The Journey Home

Epilogue

Glossary

INTRODUCTION

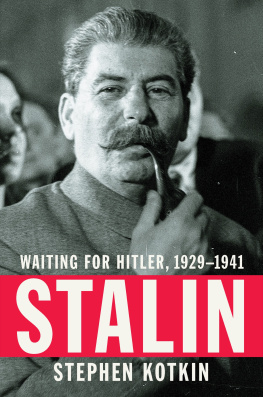

The educated world knows little - if anything at all - of thesuffering of the nomadic peoples of central Asia under therule of Stalin and the policy of collectivisation launched in 1929:least of all, of Kazakhs whose immemorial habitat comprised thatvast swathe of steppe-land from the Eastern shores of the Caspianto the great Tien Shan range of mountains which, with the Altairange to the north, forms the frontier of Kazakh territory, andtodays Kazakhstan, with China. During that period thepopulation of indigenous Kazakhs fell by approximately 1.2million from death by starvation. Over the whole of the firstdecade and a half of effective Soviet Communist rule, from - say -around 1923, some 1.73 million Kazakhs out of a previouspopulation of around 4 million were lost by starvation or executionor, in the case of about a tenth of that number, by flight to othercountries in the region, notably China, Afghanistan and Iran. Thisis a story of willed catastrophe, on a scale of ideological horrorunequalled even in the total record of Stalins tyranny, and onlysubsequently surpassed by Mao Tse-tung and Pol Pot.

It comprised not only the massacre of people in vast numbersbut the destruction of a nomadic culture and way of life ofantiquity such as defined in essence the Kazakh nation. In todaysterms, it would unquestionably justify the accusation of genocide.It is a matter of joyful irony that it was the Leninist principle ofrecognising, within the ruthless matrix of his Marxist empire, thefactor of ethnic nationalities, with their puppet governments ofindigenous Soviet toadies and their phoney territorial autonomies,which has resulted today in the Republic of Kazakhstan, the ninthbiggest country in the world, no less, and no less than the majoreconomic presence in central Asia with its vast capital of Caspianoil, and with a population of more than 14 million of which overhalf is of Kazakh blood. Blood carries memories; and todayKazakhs are, to a man and a woman, the descendants of thatremnant who somehow survived the privations of the appallingperiod this book covers.

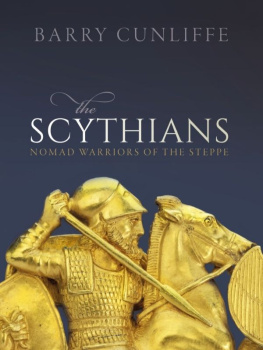

The Kazakh people were no strangers to Russian persecutionand exploitation. For three quarters of a century prior to the timewhen Mukhamet Shayakhmetov was born (1922), Russia had beenestablished as colonial authority across all Turkic-speaking centralAsia (less the Uighurs of Sinkiang), involving the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz,Turkmens and Uzbeks; and indeed their Farsi-speaking neighbourstowards the Afghan border, the Tadjiks. All are of Moslemadherence, converted at various points from the seventh centuryonwards, albeit some of them quite recently and fairly loosely. Theyhad a sustained if secret allegiance to their shamanistic inheritance,which in turn had coloured that combination of Buddhist,Zoroastrian and Nestorian Christian amalgam comprising whattoday we term tengrism: a faith in the unity of creation with Manat its centre and in communion with it, and of Man as the inheritorof a potential gift of ecstatic enlightenment. All this was mysticallyexercised among the Kazakhs in the rituals of their immenselyancient nomadic and transhumant existence, based upon theirhorse- and camel-borne economy of herding sheep and goats acrossthe vast breadth of the steppe, and subject to a climate of extremeconditions, especially in winter. With it came an oral tradition ofsong and saga and poetry, and a flowering in the written corpus ofwork of the Kazakh Abai Kunanbaev, who had died in 1904. To allthis young Mukhamet Shayakhmetov was a devout heir. His was away of life traceable down the centuries from the Scythians ofGreek mythology and classical times, from the panning of gold bythe sacred (and secret) means of the fleece, and indeed from thetechniques of domesticating the wild horse for humantransportation, first devised on these very steppes some seventhousand years ago.

From early in their colonial intrusion, the Russians had sought tobreak, or at least override, the traditional Kazakh nomadic life anddefiant clan allegiances, its lines of authority descending from itsvarious Khans, and the complex weave of its three zhuzes - of the Senior of the partially settled south and south-east, containing theirancient cities; the Middle zhuz of the families and clans of whichMukhamet Shayakhmetov was a part, in the north-east and north ofKazakh territory; and the Junior zhuz of the west. In the mid-nineteenthcentury the Russians had offered to protect the steppelandinhabitants from the ravages of Jungarian invaders from across theEastern mountain borders of what is today Chinese and Mongolianterritory. Their price was an unwanted colonial control and Russiansettlement which, by 1854, had become energetic and determined.

From their base in Fort Verny, soon to be renamed Alma Ata(todays Almaty), Tsarist Russia presided over relentlessresettlement of Russian peasantry. All Kazakh land serving thenomadic way of life was deemed to belong to the Russian state.The newcomers were invariably and advisedly armed. In 1880, theRussian commander at Fort Verny declared, as he said, in therequirement of sincerity that Our business here is a Russian one,first and foremost, and all the land populated by the Kazakhs is nottheir own The Russian settled elements must force them off theland or lead them into oblivion. At the same time, the territory ofthe Kazakhs (or Kyrgyz, as they were commonly termed, in theabsence of distinction from their ethnic neighbours settled in themountains of the extreme southeast of the territory), was used as adumping ground or place of exile for those elements or individualsSt Petersburg deemed subversive. Those exiled included thenovelist Feodor Dostoevsky, dispatched to Semipalatinsk, the mainurban centre of the territory covered by the story of this work, andTaras Shevchenko, the Ukrainian writer and poet, to Mangyshlak.

By 1916, six years before Mukhamet Shayakhmetovs birth andtwo years into the conflict in which Russia was locked withGermany, the Kazakhs rose in steppe-wide revolt against theirRussian masters. No fewer than 385,000 Kazakhs, the cream of theentire generation of males, were to be drafted into the Tsarist army,to provide backing for the front line against the Kaisers armies. In1914-15 alone, 260,000 head of Kazakh livestock wererequisitioned by the Russians without a kopek of compensation.Seizing that moment of evident vulnerability in St Petersburg, agroup of Kazakh patriots, headed by the nationalist intellectuals ofAlash Orda, raised the flag of Kazakh independence. The rebellionwas ruthlessly quelled. Thousands of patriots died, thousands morefled: a few, awaiting execution, were saved by the revolution ofFebruary 1917, which ended Romanov Tsarist rule, and led toRussias withdrawal from the Great War.