At Home

on the

Kazakh Steppe

A Peace Corps Memoir

Janet Givens

Also available in print and large print versions.

Published by Birch Tree Books, 2015

Distributed by Smashwords

Text Copyright Janet Givens 2014, 2015

Cover design Copyright Anne McKinsey 2014

Cover Photograph Copyright Janet Givens 2006

Author Image Copyright Melody Starkweather 2014

Ebook formatting by www.ebooklaunch.com

Second Edition

The author reserves all rights. No part of this eBookmay be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without writtenconsent of the author except in the case of brief quotationsembedded in critical articles or reviews.

Originally Published by Ant Press, 2014

Also available in print and large print versions.

DEDICATED

to

Gulzhahan Zhalelova Tazhitova

without whom this would have been very differentstory

and

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev

without whom this story never would have been

W ith gratefulrecognition of the work the Peace Corps continues to do around theworld and in the hope that the work of peace and understanding theydo so well will someday be unnecessary.

O n that trip it was my goodfortune to be wrong;

being mistaken is the essence of the travelerstale.

Paul Theroux (1941 -) Riding theIron Rooster

Preface

W here does one begin? Atthe beginning, so it has been said. But just where does my PeaceCorps memoir start?

While the story I tell here begins in Augustof 2004, when my husband and I finally arrived at our Peace Corpsassigned work site, I like to think it actually began in the late1970s, when I first heard that one could join the Peace Corps laterin life. It was during the presidency of Jimmie Carter (1977-1981)and the American media was filled with the story of Miss Lillian,the presidents mother, who had joined the Peace Corps some tenyears before, at age 67, serving in India as a nurse.

Before I heard her story, Id thought PeaceCorps service was only for the young, recently graduated collegestudent, one who had neither dependents nor career. I was thrilledto learn I was wrong.

By the late 1970s, I had both dependents anda career. But at least I knew that someday, perhaps when I was alsoin my 60s, I might still live out that old high school dream: toserve in the American Peace Corps. It would take me another thirtyyears to see my dream come true.

My story ends with Miss Lillian too, in away. During the summer following our return home, I found a copy ofher book, Away From Home: Letters to My Family, in a usedbookstore in Plains, Georgia. This was her Peace Corpsstory. Like Lillian Carter, I too had written letters home.During my two years in Kazakhstan, Id sent seventeen emailupdates to no less than 108 people. I had my journals too, and Ihad my memories. And so, in January 2007, I sat down at my computerand got to work.

Writing this book has allowed me to relivethe highs and the lows of those two years in slow motion. I wrotefirst to understand my experience. Then I rewrote, and rewrote, sothat I could share that experience with a broad array ofreaders.

My hope is that, in reading my story, youllcome to recognize two things.

The first is how vital it is that we humanslearn to connect with one another over the artificial barriers ofage, religion, gender, and culture. We can connect acrossthese barriers. Indeed, as our world continues to get smaller, Ibelieve we must.

The second is that opportunities to live outold dreams are all around us, if we can just see them. If ever youare presented with such an opportunity, I urge you to jump into itwholeheartedly. It is a gift not to be ignored.

Putting my story to paper has been, to pullfrom memoirist Anas Nin, a most delicious undertaking. She oncesaid that memoirists get to live their life twice. There is theliving, she wrote, and then there is the writing. There is thesecond tasting, the delayed reaction.

This is just one story; its my story, of myexperience, and the way I remember it. I encourage you to go toKazakhstan and experience for yourself the gracious hospitality andwarm embrace of the Kazakh people.

Table of Contents

Studying culture without experiencing culture shockis like practicing swimming without experiencing water.

Geert Hofstede (1928 -)

Arrival

I was 55 when I finallystepped off the train into blinding sunshine and a new life inKazakhstan. Half a world away from the life Id had inPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, I felt proud to finally be a PeaceCorps volunteer. I was also determined to be successful, and Inaively thought I knew what that success would look like: Id makefriends for America in the post 9/11 era.

To do this, Id left behind a life I loved,given away a dog I adored, and abandoned the financial securitythat my work in Philadelphia had promised. I knew there was much Ididnt yet know about Kazakhstan and her history, culture, andpeople, but with an MA in sociology, my more recent experience as apsychotherapist, and my husband by my side, I thought I had all Ineeded to succeed.

The day my husband Woody and I got off thattrain, wed already been in Kazakhstan for nearly three months,been trained in the Russian languagehe a bit better thanIlearned about a few cultural differences wed meet, and takenpractice classes in how to teach English as a second language, ourjob for the next two years.

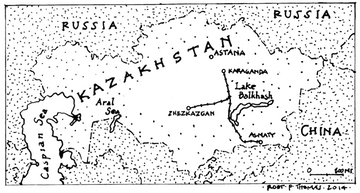

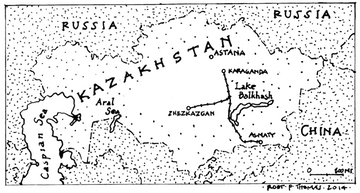

Our assigned destination, Zhezkazganoncecontrolled by the now defunct Soviet Union and built with laborfrom the gulags to house the workers for the nearby coppermineswasnt much like my City of Brotherly Love, which had beenlaid out in a systematic grid pattern by the Quaker William Penn inthe 17th century, and anchored by no less than five public parks.Nor was it the tiny seaside town of Chincoteague, Virginia, wherewed lived temporarily after our Philadelphia house was sold, whilewaiting for our Peace Corps departure. In Zhezkazgan, there wouldbe no weekly curbside garbage pickup, no opportunity to walk thebeach, and no sound of migrating birds overhead. Wed be there fortwo years.

As I squinted in the glare of the sun, ayoung woman with bright red hair and denim overalls broke throughthe small crowd of locals that had come to welcome us and thrust ahuge yellow bouquet into my hands.

Welcome, she said in perfectly passableEnglish, except that I didnt understand her. These are foryou.

Without thinking, I offered her one of theRussian phrases Id committed to memory during training.

Meenya zavoot, Janet. Kak vaszavoot? (My name is Janet. What is yours?)

Why hadnt I said the more appropriateSpaceba I wondered immediately. Or, the even moreappropriate Thank you since shed spoken to me in English?

At least I understood her name: Natasha, thefourth Natasha Id met since wed been in Kazakhstan. Nevertheless,she seemed neither to notice nor care about my faux pas andmelded back into the welcoming crowd, which was chattering in alanguage I could not recognize.

About half a dozen women and nearly thatmany men were there to meet us and I let my gaze fall on each face,wondering how well I would know these people before my time herewas over. I smiled as I caught each eye. A few of the men had goneback into the train, directed there by the women whom I assumedwere their wives, to fetch our luggage.

Our luggage. It had become an embarrassmentto me over the three months since wed arrived in the country. Wesimply had too much. Id known it when we first flew out of DullesInternational Airport and had to pay $400 in overweight charges.Id known it after our initial weekend in Almaty, Kazakhstansformer capital (and, in 2004, still its major city) when we had toleave a suitcase behind with Peace Corps staff in order to fit intothe car to ride to our first home stay.