David Ekerdt - Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life

Here you can read online David Ekerdt - Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Columbia University Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life

- Author:

- Publisher:Columbia University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

David Ekerdt: author's other books

Who wrote Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

DOWNSIZING

DOWNSIZING

Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life

DAVID J. EKERDT

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support for this book provided by Publishers Circle member Bruno A. Quinson.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54855-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ekerdt, David J. (David Joseph), 1949 author.

Title: Downsizing : confronting our possessions in later life / David J. Ekerdt.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050913 (print) | LCCN 2019050914 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231189804 (cloth) | ISBN 9780231189811 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9780231548557 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: House cleaning. | Orderliness. | Older peopleConduct of life.

Classification: LCC TX324 .E34 2020 (print) | LCC TX324 (ebook) | DDC 648/.5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050913

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050914

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

FOR PEGGY, WITH WHOM I HAVE ACCUMULATED MUCH

C lare Twomey is a British ceramics artist whose exhibits invite members of the public to interact with her work. One such exhibit, titled Forever, was displayed at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, my hometown, in 20102011. The artist had earlier visited the museum to view a famous antique pottery collection consisting of 1,345 items that the museum is required to keep in trust and intact forever. The collection gave her an idea.

Twomey selected one item in the collection, a two-handled cup dating to 1720, and had it reproduced 1,345 times. She created an installation at the museum in which the cups were placed in rows on long tables, with numbers beside them. Museum patrons were invited to view the identical cups, select one that they would like to own, and write down the number of that cup to submit in a weekly drawing. Through these drawings, the cups were gradually assigned to people. The exhibit was extremely popular.

If you were assigned a cup, you were notified, and your name was put beside it. You were required to sign a deed in which you pledged to care for the cup, value it, and display it forever, just like the pottery in the museums collection. The entire encounter among artist, objects, and the public was, according to Clare Twomeys website, meant to explore ideas of permanence, responsibility, memory, desirability, and value.

At the time of Forever, I had been conducting research on older people, possessions, and downsizing for several years. This exhibition encapsulated the problem: people think that they must keep certain things forever. The consumption of mass-produced goods is an astonishing phenomenon. Fifty identical sets of fine china came out of some factory one day. One set came to be owned by my grandmother, and one set came to be owned by your grandmother, and each grandmother took the china home and made it hers. Today we can never separate the china from the family because it was hers, and our familys set is not at all the same as the set that your family has.

I wanted to win one of the museums cups and smash it on a YouTube video: Take that, Clare Twomey. Its only a cup! I kept submitting my name for a cup, but I never won. When distribution day came at end of the three-month exhibit, people came in to get their cups and sign the deed promising to care for the cup forever. Thirty of the cups were not claimed, so the exhibit went into a second round. People were now invited to write and submit a full formal museum label of the kind that could be displayed beside a cup. Among the hundreds of submissions, thirty label writers would be chosen to get a cup. So I wrote a label, and finally I got a cup.

To conclude this exhibit, the director of the museum and the artist herself each picked a contributed label to feature on the museums website. The directors pick for the label read in part:

This Cup is a reflection of my dedication of support to our museum and to the ideas of permanence, responsibility, memory, desirability and value as they relate to art and its preservation in our beautiful city. The Cup is displayed here in my home, enclosed in this dedicated cabinet shelf, as a daily reminder of my pledge from 2010, Forever.

Such sentiment was perfectly consistent with the stated intention for the exhibit: to highlight responsibility for the protection and conservation of objects. For her part, Clare Twomey selected my label. I had given the artwork a title and wrote, in part:

Not Forever. For a while. The title for this cup gently disputes the impossible promise of forever. Material goods such as ceramics can endure, but human frailty and mortality put a bound on the commitments of individual lives. For a while is all we can promise.

After I had argued with the entire premise of the exhibit, Clare Twomey picked my label. For this choice, I have to admire the artist, because she knows that I know that she knows exactly what she is up to. She is inducing 1,345 people to behave as though mass-produced goods are entirely special, personal, singular, and inalienable to them. And that is genius!

As for my cup, I do care for it. I display it in a glass case, with the label, because there is a heck of a good story to tell when anyone expresses any passing interest in my piece of salt-glazed stoneware.

This is a book about possessing things both cherished and ordinary. The possessing and the things themselves can be rolled into a termmaterial convoyin order to convey the idea that belongings accompany our lives across time. This book takes a special interest in the material convoy as it crests in size at midlife and its fate begins to become an issue for oneself and othersespecially in later life when, in relocating from larger to smaller quarters, getting rid of possessions becomes necessary. I report findings from research among older Americans who have recently relocated and divested themselves of possessions and among others who are aware that they may someday need to move. This research has taken two directions that diverge from most other approaches to the question of aging and possessions, which tend to concentrate on static and single things.

First, during this experiencepotential or actual relocation in later lifepossessions are metaphorically in motion, on their way to new places and to being viewed in new ways. When things reside or stay with people, when they are kept, they have meaning as part of a human-material bond. Taking things out of their accustomed places to move them creates what Nicky Gregson calls a gap in accommodation. In that gap the human-material bond is exposed to scrutiny. They prompt questions: Why do I have this or keep this? Should I continue to do so?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

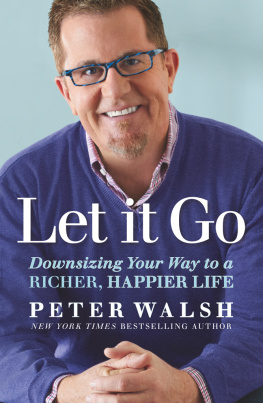

Similar books «Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life»

Look at similar books to Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.