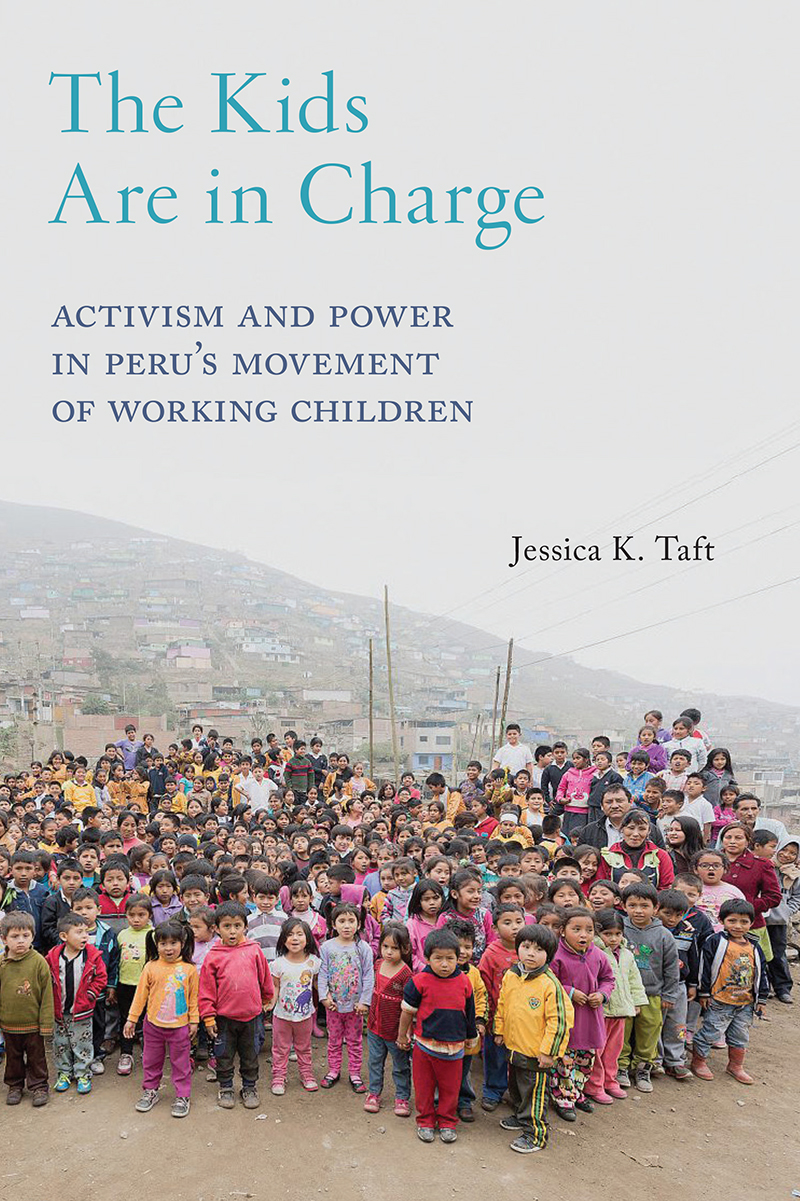

Jessica K. Taft - The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children

Here you can read online Jessica K. Taft - The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: New York University Press (NYU), genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children

- Author:

- Publisher:New York University Press (NYU)

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jessica K. Taft: author's other books

Who wrote The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Critical Perspectives on Youth

General Editors: Amy L. Best, Lorena Garcia, and Jessica K. Taft

Fast-Food Kids: French Fries, Lunch Lines, and Social Ties

Amy L. Best

White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America

Margaret A. Hagerman

Growing Up Queer: Kids and the Remaking of LGBTQ Identity

Mary Robertson

The Kids Are in Charge: Activism and Power in Perus Movement of Working Children

Jessica K. Taft

Jessica K. Taft

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN: 978-1-4798-6299-3 (hardback)

ISBN: 978-1-4798-5450-9 (paperback)

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

For all the kids raising their voices for justice and dignity and all the adults who listen and take them seriously

On July 28, 2015, Perus National Independence Day, over a hundred working children and their allies marched through the streets of Lima, demanding that their national government recognize their rights as workers and as political subjects. Their press release, banners, and flyers called for the government to cease trying to abolish child labor and to instead focus on protecting working children from exploitation and providing them with better social services and schools. Children, they argued, should be allowed to work so long as that work is dignified and is not causing them harm. Further, they asked the authorities to respect their political organization, the Movimiento Nacional de Nios, Nias y Adolescentes Trabajadores Organizados del Per (MNNATSOP, the Peruvian National Movement of Organized Working Children and Adolescents), to include them in all policy decisions related to working children, and to listen and take into account what we propose for our lives and our communities. This march was not just attended and led by children, but was entirely planned by a committee of ten young activists, ages eleven to fifteen, who had been elected to leadership by their peers in the movement. They were supported in this organizing by four colaboradores (adult supporters), but the young people themselves were the primary decision makers, wrote all of the materials for the event, and did the outreach and publicity.

The march started out fairly subdued, with just a handful of the young activists chanting. Led by eleven-year-old Andrea and fifteen-year-old Patricia, the NATs (nios y adolescentes trabajadores, or working children and adolescents) quickly became more comfortable, getting louder and louder as they yelled, Alerta! Alerta! Alerta que camina: los NATS organizados de Amrica Latina! and Los nios lo dicen y tienen la razn, s al trabajo digno y no a la explotacin.rhythm with the chants. Despite its small size, the march captured the attention of many bystanders, who expressed surprise at seeing children leading a march, as well as curiosity about the movements reasons for defending childrens right to work. After moving through the center of Lima, past several plazas full of people, the group stopped in a park and several teenage leaders spoke about why they were there. They expressed their firm belief in their rights to political, economic, and social inclusion, and the need for then president Ollanta Humala to follow through on the commitments he had made to children, including to working children. The crowd of both participants and bystanders cheered loudly after each speech, and the young activists wrapped up the event with an escalating call-and-response series of Que vivan los NATs! Que vivan!

As the event was winding down, one of the colaboradores asked my partner and me whether we would help out by walking Andrea back to her home in a nearby neighborhood. A diminutive Afro-Peruvian with an infectious smile, Andrea was overflowing with energy and practically bounced through the streets as she led us back toward her house. Although we knew our way around the area fairly well, we let Andrea guide us, following her directions on which route to take to her house. Along the way, she told us proudly that she knows this area like the palm of my hand. She pointed out various landmarks, including her favorite place to eat ceviche, greeted a few neighbors as we got closer to her house, and kept up a running commentary about how my partner and I should be careful because we are foreigners and people might try to cheat or steal from us. She warned us not to go down certain streets, to avoid a particular park, and to be alert because her neighborhood is not safe. In a crowded area around the Plaza de Armas, she paused to make sure we were all still together, ushering my partner forward when he fell behind a bit. I tried to reassure her and explained that we had lived in Lima for many months, and that we both travel a lot through various neighborhoods of Lima on foot and feel comfortable in these spaces. When we got to her house, she smiled, told us this is where she lives, and then offered to walk us back toward the center of the city so we could catch a bus back to our apartment. I gently reminded her that the whole point of our journey with her was that the colaboradores wanted us to take her home, not the other way around! She reluctantly agreed to this, but reminded us one last time to be careful and gave me her cell phone number, in case you get into any trouble.

Both the march itself and our interactions with Andrea that day are reflections of the critical approach to childhood that has been developed over the past forty years by the Peruvian movement of working children. In the march, working children engaged in a public politics of protest, arguing for childrens greater inclusion in economic and political life. They demonstrated their ability to organize and engage in collective political action and challenged widespread assumptions about child workers. Against increasingly globalized narratives that imagine the ideal childhood as a time of only play and learning, or as a time without responsibilities, the NATs argued directly for their right to work a limited number of hours in safe, dignified, and protected conditions and explicitly claimed that work and a happy childhood are not necessarily incompatible. They also emphasized their own political and economic capabilities, redefined childhood as a space of meaningful and critical participation, and identified themselves as public subjects and collective actors, directly challenging more widespread discourses that frame children only as objects of socialization and as innocent, passive, and privatized individuals. But Perus movement of working children is not just interested in childrens political and economic inclusion; it also seeks to transform intergenerational relationships, making them more egalitarian and increasing childrens power and authority in their everyday interactions with adults. This everyday intergenerational politics was evident in Andreas confidence and her totally empowered take-charge attitude. Andrea is not just an eleven-year-old activist with political experience who can lead a march and express her own fully developed arguments about childrens rights; she is also an eleven-year-old who knows her way around her city, trusts herself to effectively navigate its potential dangers, and is not afraid to tell two adults that she is more knowledgeable and skilled at this than they are. The fact that we were foreigners certainly helped mark us as less competent than Peruvian adults, but Andrea claimed significant power and authority in this intergenerational interaction. Andrea entirely rejected the idea that she needed protection, positioning herself instead as a protector; she saw herself as being in charge of and responsible for us, not the other way around. Like many other NATs involved in the movement of working children, Andrea has learned to value her expertise and to question assumed intergenerational hierarchies that place adults above children.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children»

Look at similar books to The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The kids are in charge : activism and power in Perus movement of working children and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.