All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

O NE W ORLD is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

He is part of an assembling crowd, anonymous thousands off the buses and trains, people in narrow columns tramping over the swing bridge above the river, and even if they are not a migration or a revolution, some vast shaking of the soul, they bring with them the body heat of a great city and their own small reveries and desperations, the unseen something that haunts the day.

INTRODUCTION

There is a line between Us and Them, and Ive seen it. Or at least part of it. Along the Arizona-Mexico borderin the American town of Nogales and the county of Santa Cruzis a cloud-scraping thirty-foot fence made of vertical steel rods lodged in concrete. In theory, border fences like this are built to keep citizens from both countries on their respective sides of the border. In truth, the fence, erected by Americans, is intended to keep Mexicans in Mexico. And to keep AmericaAmerican. Safe from invasion and confusion, strong in its defenses, discerning in its welcome.

Its only mildly effective.

Back when I visited the border, I was the anchor of a cable news show, and the border had become a fairly obsessive focus of mine. I wasnt alone. The border had become an obsession for a lot of people, not least the men and women assigned to police it, the American border patrol. Our country was spending billions of dollars guarding that border with agents, drones, cameras, and exotic military hardware. The fence was only the most visible sign of our extravagant vigilanceand I went to Nogales to see it up close.

We took a break from shooting to eat lunch, and I noticed that the border patrol had stationed a sentry further down along the barrier. We, meanwhile, had cameras with us, lights, makeup artistsa whole crew. But neither law enforcement nor the media presence did anything to stop a pair of fruit sellers on the Mexican side of the wall from lassoing a rope to the top of a border fence post, climbing up, and rappelling down to the American side of the border. All in broad daylight, in under five minutes. Those two fruit sellers made a mockery of that walland it was mesmerizing. Here was an act of alchemy: The two of them, in an instant, transformed themselves from Mexicansin the land of their ancestors, feet planted on a patch of earth to which they unquestionably belongedto intruders.

All of a sudden, they were part of a different story, one that they would in some way change, if only by adding to its supply of readily available and delicious fruit. And they werent just crossing a visible wall marking an invisible border. They were crossing a line inside themselves: between the native and the immigrant, the one who belonged and the uninvited stranger. They had become something new. That sprint over the wall was, in microcosm, the adventure story that has defined and threatened human existence from the beginninga movement from one land to another. But was it flight or invasion or just an act of survival? Those fruit sellers hit the ground, composed themselves in a blink, and embarked, with quick steps, on the days business. And nobody said a word.

Stories like thisabout immigrants, refugees, exiles, and internal migrantshave always had a hold on me, perhaps because of my own familys history of migrations, escapes, settlement, assimilation, and, um, amnesia. But these are universal struggles, too, and they have reappeared again and again in my professional life: when I was the editor of a music magazine, the director of a global nonprofit, a political journalist. Usually, we understand them as human rights concerns or battles over resources like land or jobs or government assistance. But I, at least, also see them as complicated romances.

For a few months in 2013, I spent a not-insignificant amount of time researching Maricopa County, Arizona, intrigued by the twisted drama unfolding in a community of retirees; descendants of homesteaders; Latinos whose families had been there for centuries; Native Americans whose families had been there for millennia; and new immigrants who had only just crossed deserts or oceans of paperwork to get there from Mexico and Central America. In all of that longing and violence, possessiveness and angerin the battles between these waves of immigrants and exiles, refugees and nativeswhat did it mean to belong? Just as crucially: Who got to decide? Each answer gave rise to new questions.

In reality, immigration isnt just outside versus inside, the lawful versus the illegal. Its a story about the messy, sad, terrifying, and occasionally beautiful experience of leaving one place and starting over in another. I realized that my interest in the subject wasnt simply about the politics, but in immigration as an interior actbecoming something newand as the social act of losing one home and making another. Immigration raises into relief some of our most basic existential questions: Who am I? Where do I belong? And in that way, its inextricably tied to an exploration of American identity. Here we are, in a nation of immigrants, exiles, captives, refugees, and displaced natives, staring together into that existential void.

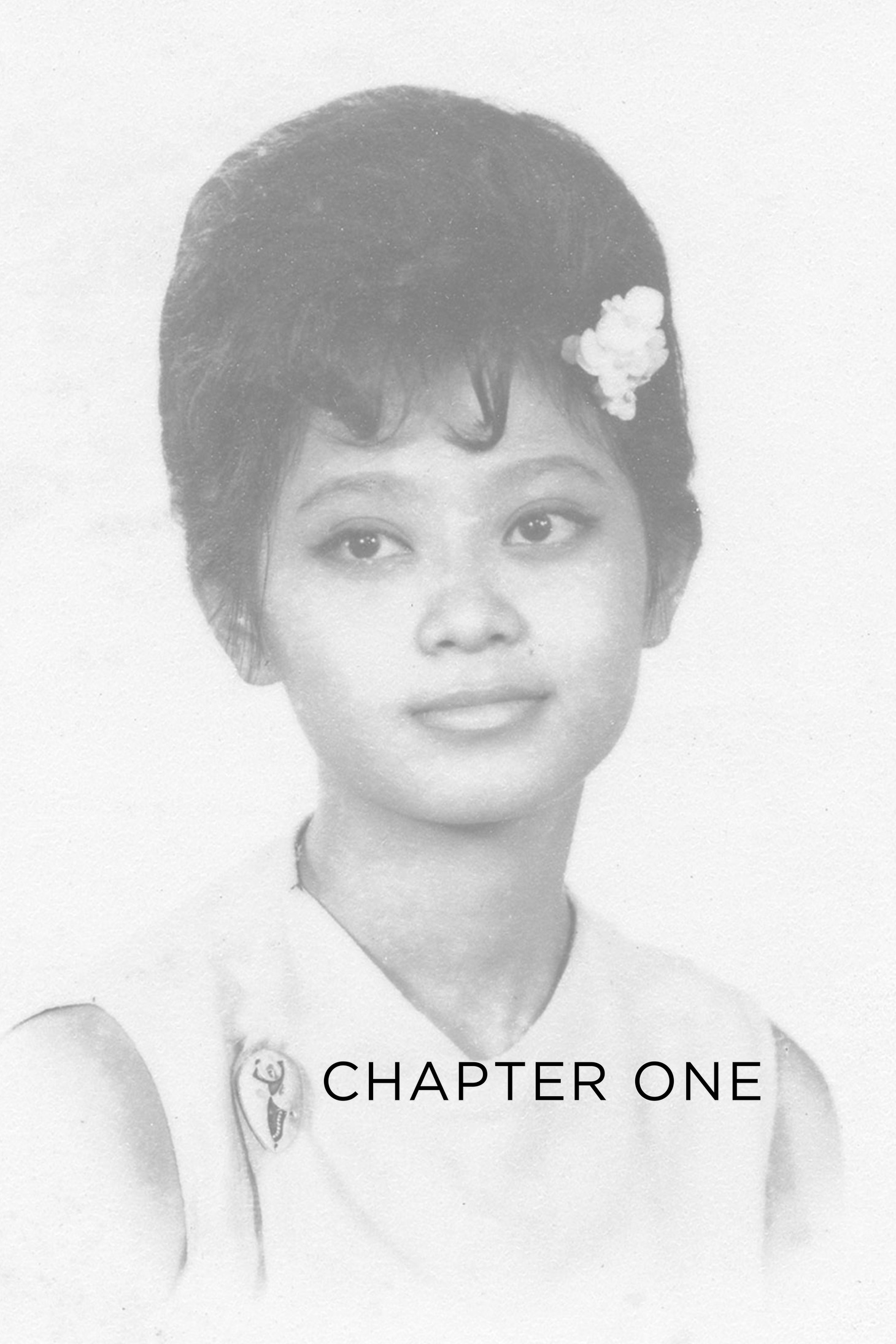

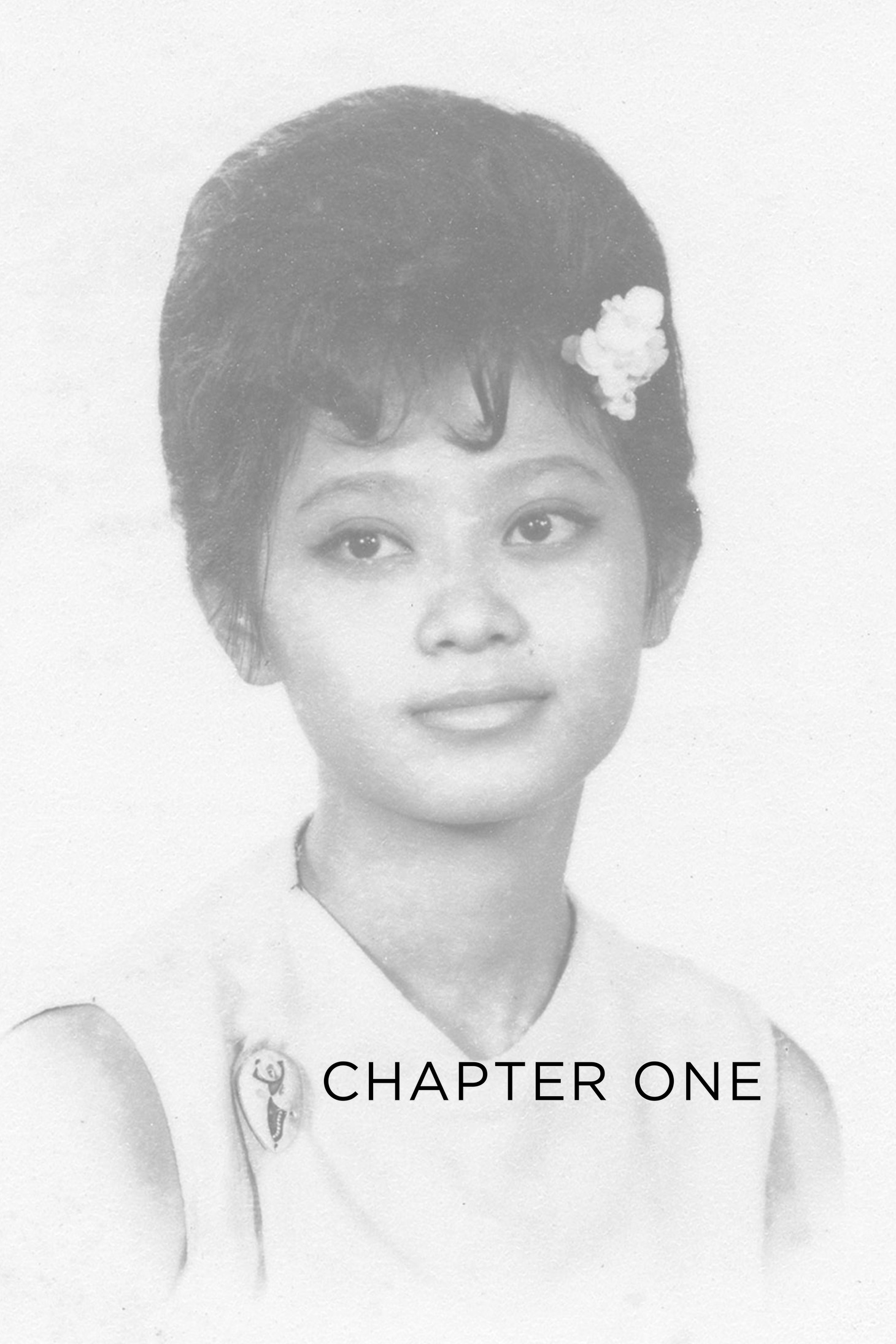

These are the questions many of us either devote our lives to answering or spend our lives evading. They are questions Ive asked myselfwithout much in the way of conclusionwhen I thought about my Burmese mother and American father, when I thought about the country that pushed and pulled me, when I thought about friendship and loneliness and the possibility of having my own child and attempting to guide that child to some inextricable truth about Our People. All this contemplation made me identity hungry and identity fatiguedit made me want a simple answer, an easy story about who we are and why were here together. I started to see my preoccupation with immigrants, exiles, and refugeesand the attendant concerns about home and identity and belongingas the edge of a longer, more complex puzzle. Turns out, the mystery I was really trying to solve was my own.

I played a lot of solitaire growing up. I was an only child and a nerd and thus alone a lot of the time, and when I wasnt, I was asked to mind my manners and keep quiet around the adults. For most of my adolescence, I used a weathered pack of dark blue playing cards that had the logo of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters embossed in gold on the back: a pair of horses heads atop a wagon wheel. Adults would see the horse head next to the Teamsters name and laugh in disbelief that a union with alleged mafia ties would have a horses head anywhere near its logo. I hadnt yet seen