Table of Contents

In the dark of morn the light shines through the trees and reminds me of him.

APRIL 2007

In loving memory of my father, Peter Rabow

(MARCH 23, 1936DECEMBER 1, 2006)

May God remember the soul of my beloved father who has gone to his eternal rest. In tribute to his memory I pledge to perform acts of charity and goodness. May the deeds I perform and the prayers I offer help to keep his soul bound up in the bond of life as an enduring blessing. Amen.

YIZKOR, MEMORIAL SERVICE

INTRODUCTION

IN DECEMBER 2006, my father, Peter Rabow, died after an eight-month battle with lung cancer. The experience of losing a parent was deeply significant, and it affected my life on nearly every level. My busy life as a mother, wife, and entrepreneur came to a screeching halt. My body and mind felt numb. I had no choice but to take time to contemplate the matters of life and death during what I would later call my spiritual sabbatical.

Prior to my fathers death, he and I had discussed the idea of the mitzvah of tzedakah, or donating money in his memory to a charity. Wed played it out rather thoroughly, him suggesting that friends and family not send flowers but rather make donations to venues that aid people to be the best they can be and help them grow. Id suggested an organization I knew of, and he told me about ones hed had in mind. In his obituary, my family requested that friends donate to these charities.

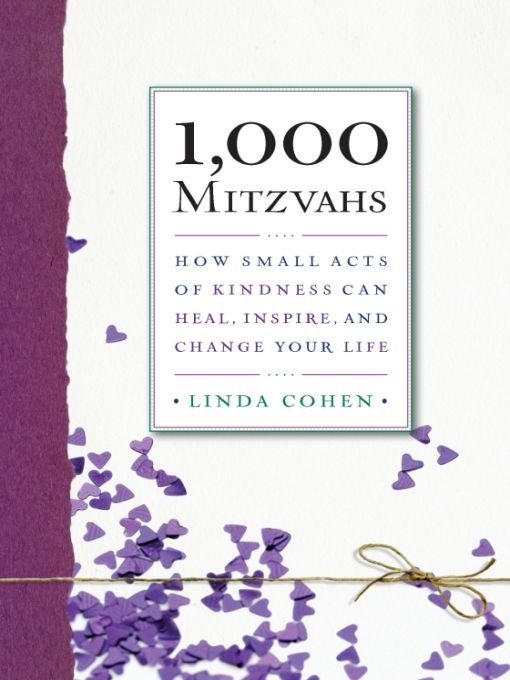

Perhaps the seeds of that conversation sparked the simple thought that awoke me in the middle of the night about a month after my fathers death. As I contemplated how meaningful it was that people had donated in the name of my father, in essence allowing his generous spirit to live on, I was inspired to begin a mitzvah project of my own to honor my fathers memory. The idea was to perform 1,000 mitzvahs. Mitzvahs are statements and principles of Jewish law and ethics contained in the Torah, or Five Books of Moses. The word mitzvah is translated as commandments. There are 613 mitzvahs. Judaism teaches that Jews are commanded to observe these mitzvahs. There are two types: Positive commandments are commandments to do something, such as, honor your mother and father; and negative commandments are commandments not to do something, such as, thou shalt not murder.

According to Chassidic teachings, the word mitzvah is derived from the Hebrew root tzavta, meaning attachment. When we act on a mitzvah, we are creating a bond or a further attachment in our relationship with God. Another rabbi I know teaches his bar and bat mitzvah students that these commandments are spiritual opportunities for connection. We create or tap into a connection with God, each other, ourselves, and our history when we engage in a mitzvah.

Many of the 613 mitzvahs cant be observed today for a variety of reasons. Some relate only to the ancient holy Temple in Israel, and they include sacrifices and service. Since the Temple doesnt exist anymore, they cant be observed. Others relate to civil procedures in Israel, and because Israel is a democracy today and is no longer governed directly by religious laws, they are also no longer valid.

An important mitzvah category is doing acts of loving kindness, also called gemilut chasadim. The Talmud, a central Jewish text, says that gemilut chasadim is greater than tzedakah (charity), because unlike tzedakah, gemilut chasadim can be done for both the rich and poor, both the living and the dead, and can be done with our actions or with money. The world is built with kindness (Psalm 89:3).

People in recent times have begun to use the word mitzvah interchangeably with doing an act of kindness because so many of the mitzvahs call upon our deep capacity for true kindness in the world. For my project and this book, that is the way I chose to interpret it, as well.

My intention from the beginning was to use this concept of doing good deeds as a way to honor my fathers memory. It felt like a proactive way to work through the pain and loss that I felt in my fathers absence. I figured the project would allow me to help others in small ways and create good feelings to compensate for the pangs of grief and sadness.

The next morning, I shared my idea with my husband, a software engineer, who suggested we create a blog to track my mitzvah project. On January 17, 2007, I posted my first blog entry to www.1000mitzvahs.org. I made a conscious decision to use the more Americanized word mitzvah, rather than the grammatically correct Hebrew plural mitzvot. Although this project is firmly rooted in my religious beliefs, it soon became apparent that it could and would be equally relevant and inspiring to all people. Throughout the project and book, I have continued to use the Americanized word mitzvahs, which I originally chose for my blog name.

The night after creating my blog and writing my first entry, I emailed several close friends to tell them about my project. I was nervous about what they would think. I wasnt accustomed to sharing the details of my personal endeavors online. I worried that someone would call me a braggart. I almost didnt send that email because of fear. The next month, I stood up at my networking group when we introduced ourselves and announced that I was taking a spiritual sabbatical from my business as a direct sales consultant and would be starting a new project: to complete and blog about 1,000 mitzvahs I would be performing in memory of my father. The immediate feedback was encouraging. People applauded my efforts and I began to relax into the new adventure I was on.

Prior to starting my blog, I never considered myself a writer. I had kept journals before but never anything that would be read and shared with others. About a month into the project, I received an email from a gentleman in Israel. His one simple comment made a light bulb go off in my head. I recognized that strangers could find my blog and were starting to follow what I was writing. That realization clarified for me that I was not the only one being inspired by this project. I was part of a greater world where ones actions affect others. In fact, each of us is part of this world where our actions of loving kindness effect others. As the months went by, I befriended men and women across the country who found my project and wrote to me. This recognition helped me gain confidence and belief that this project was something that transcended myself, my family, and my religion, and was something I must continue to share and explore further.

THE BLOG WAS an incredible tool for me. It allowed me an opportunity to share my thoughts and feelings as I moved through my grief in a very concrete way. Between the mitzvahs themselves and blogging about the actions, I stumbled onto a powerful combination for processing grief. The mitzvah project did help me remain connected to my father. I felt a deep knowing that my dad and I were on this journey together somehow. The project allowed me to think about him a great deal and to share stories about him, as well.

I began to think of the journey of loss and grief as a trip across a raging river. When you begin the journey of processing grief, you suddenly realize there is no getting around it. It has to be embraced, digested and pondered, and ultimately passed through. When I began trying to cross the river of grief, I felt as if the cold water of the river was rushing over me. I felt alive and aware but also exposed, raw, and numb. Others reached out to me to extend a hand and help me cross the river. I heard stories of others and their own losses. It was comforting when I wondered how long I would feel this way and if I would ever feel back to normal. While crossing the river, I met others who were crossing their own river of grief. We shared an experience of loss, but each one of us was ultimately on our own to cross that river. I embraced as many hands as I could and took that support while I was in the water. There were moments of normalcy, when I stopped on a rock protruding out of the water, and other times when I slipped back into the cold wetness. Slowly, I made progress crossing the river. Eventually, I offered my hand to someone who was still in the river and encouraged them to keep crossing. There were always people on both sides of the river, everyone helping each other get across.