ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

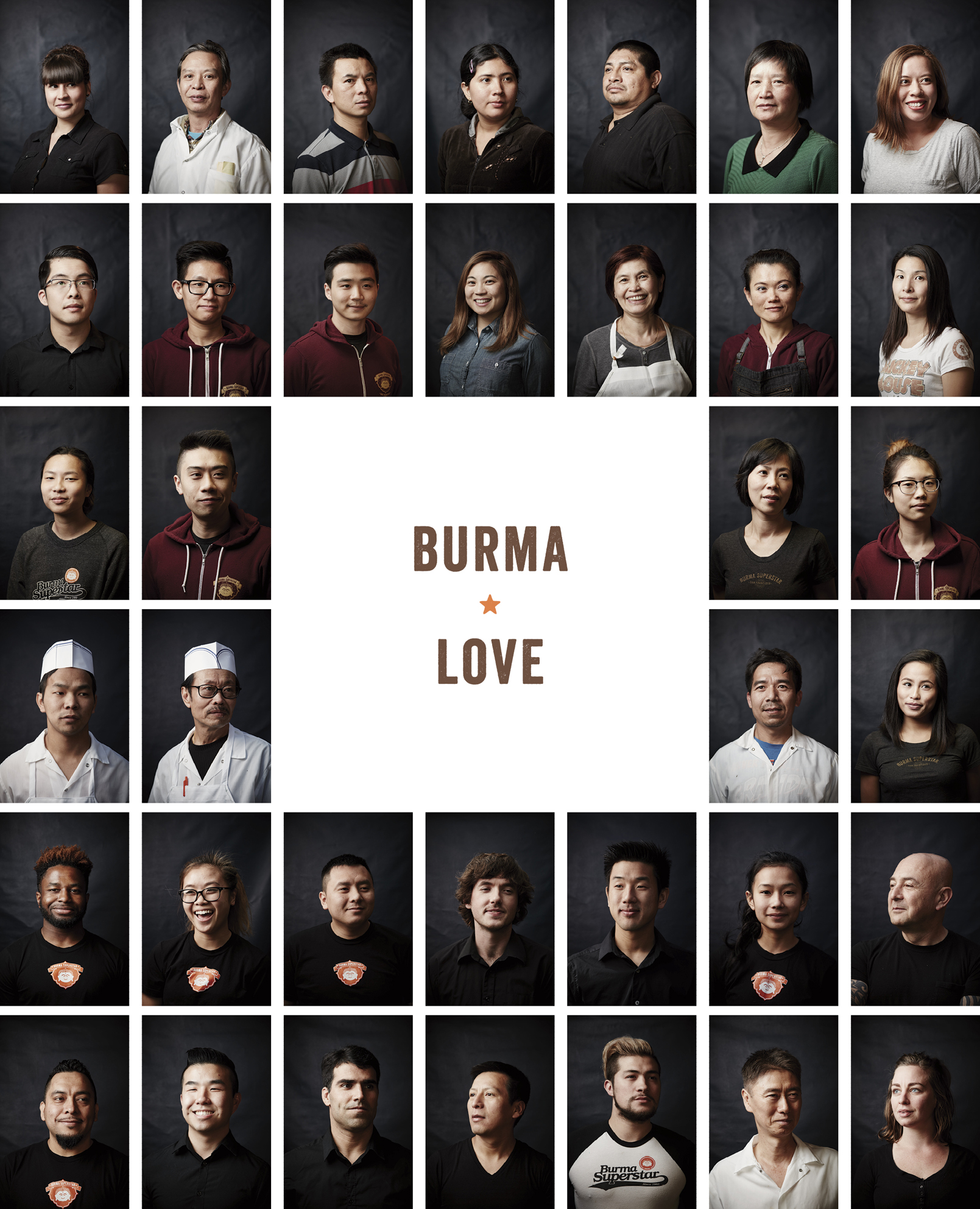

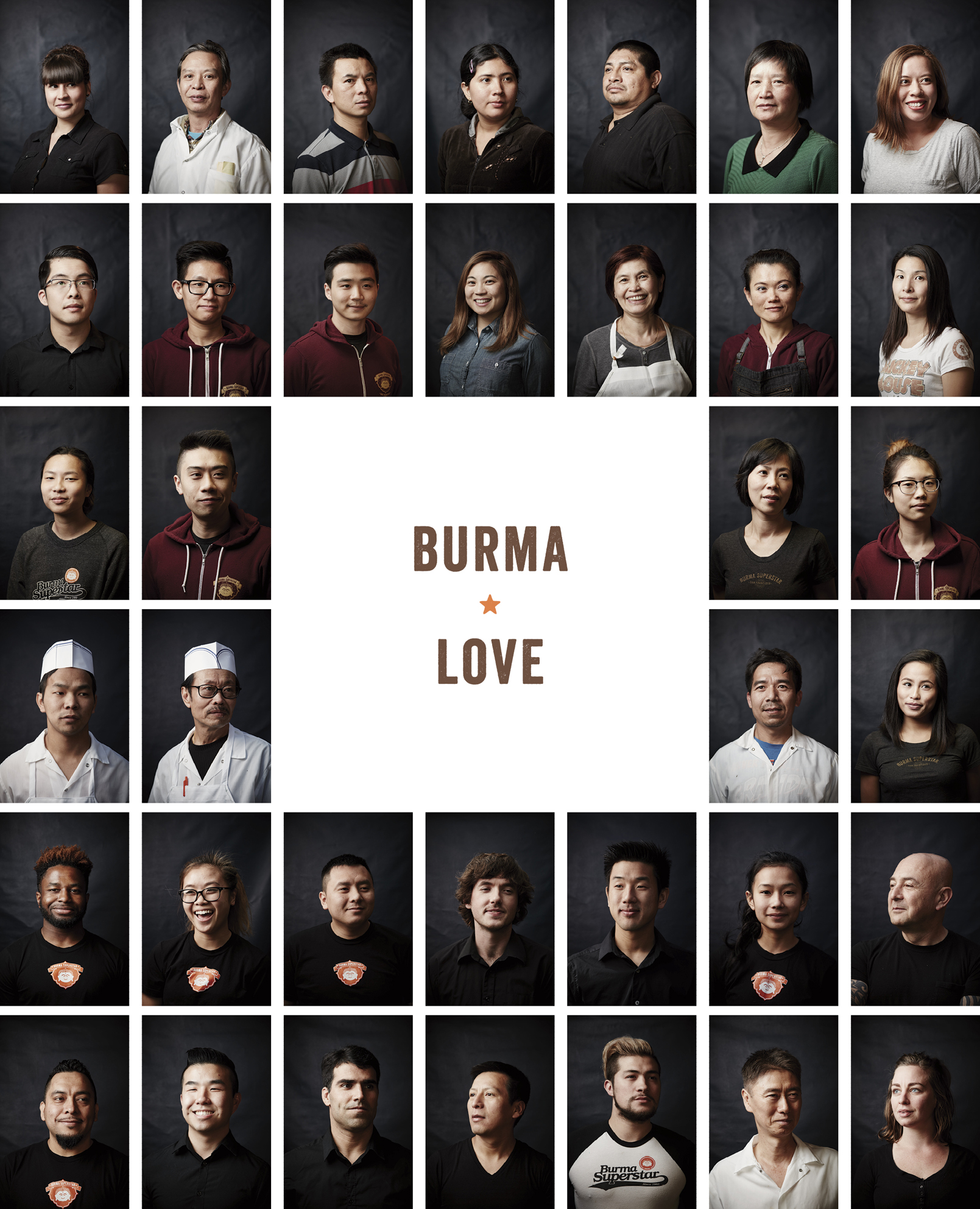

This book is at least 25 years in the making, and our thanks go out to the community that continues to support Burma Superstar.

To Joycelyn Lee, who has been instrumental in building Burma Superstar into a restaurant that has inspired countless people to learn more about Burmese food. Thank you for putting the Rainbow in Rainbow Salad and for so much more.

To my daughter, Mya, the best mohinga taste-tester in the business. May this book help you continue to connect with your heritage.

To Carole Bidnick, my agent, who somehow got me to sit down and think that this book was a possibility. Your patience with me was truly remarkable. (And sorry that it literally took us years to return your call.)

To Ten Speed Press

Jenny Wapner, our editor, who supported our quest to dig into the world of fermented tea and let us dedicate several pages to describing how it is made.

Kara Plikaitis, our fearless designer, who put out a wok fire on set during a photo shoot and spent extra time to ensure that the photography was always in sync with the story.

Thanks are also owed to Rachel Markowitz for thoroughly copy editing the text (and even testing a recipe), Elisabeth Beller for proofreading it, Ken Della Penta for indexing it, Erin Welke, for helping get the word out about Burma Superstarand Myanmar itself, and Ashley Pierce, Kate Bolen, Lizzie Allen, and everyone else at Ten Speed HQ who supported the book behind the scenes. Thank you.

To Our Book Team

Kate Leahy, my coauthor, who not only knows how hot it gets in Bagan in the off-season but also can now cook like a Burmese lady. Her wok was sacrificed in the fire.

John Lee, our photographer, who not only captured the sense of change in Myanmar today but also, during the course of making this book, fended off monkeys at Mt Popa and spent hours hanging out at our restaurants to capture images of our staff.

Lillian Kang, who not only is a talented food stylist in her own right but also got us all to laugh about that wok fire (after the fact). And props to Ethel Brennan (for props).

To Olga Katsnelson and her team for working with us to promote the book and Burmese food.

To the restaurant staff, past and present, and friends who have supported the restaurant, especially (in alphabetical order) Afoo, Pa Bawi, Jacky Chan, Dewey Chi, Chuck Chin, Soo Chyung, Ma Htay, Kent Li, Har San and Rahima, Ma Sein, Carl Velasco, Lynda Vong, Meida Wang, Karen Wong, Daw Yee, and the entire Wu family. The success of Burma Superstar would also not have been possible if it wasnt for your involvement. Special thanks to Nin Thawng, who came in early to coach us on recipes (especially curries), Osama Asif, who was instrumental in connecting us with Carole and helped launch the project internally while manager of the Oakland restaurant, and Tiyobestia Shibabaw, who also helped coordinate cooking sessions and interviews.

To our Mission Street team, especially Jett Yang, for joining us on our Namhsan adventures equipped with a suitcase filled with MREs in case we got stuck in the middle of nowhere (excellent planning!); Irene Cho, who came on to help promote the book and the fermented tea leaf story with her signature amount of enthusiasm and attention to detail; and Amy Lee, who not only was instrumental in organizing our research trips to Myanmar but who also helped vet ideas during the process of creating this book. (Thank you for ensuring we never missed a flight.) Thanks are also due to Jenny Su for always keeping us on track, Ma Mee Shu for taking such good care of Mya, Ryan Hughes for keeping me organized, and everyone else who has worked behind the scenes to make Burma Superstar and Burma Love what they are today. (My apologies for all of those meetings.)

To our colleagues in Myanmar who have become friends, especially Nelson Rweel, Myo Win Aung, Khin Ye Yupar Aye, and Bryan Leung. Thank you for sharing your country with us. And to Sarah Oh, our American friend in Yangon, who shared her side of the historic election with us.

To Andrea Nguyen, for tofu support and for connecting Kate with Karen Coates, and to Karen Coates for sharing her Pa-O beans story and for her detailed reporting from Myanmars countryside.

To Maggie Hicks at the International Rescue Committee and to Zack Reidman and Deepa Iyer of New Roots for helping us better understand the IRC story and refugee life in the Bay Area.

I would also like to thank Rich Cho, James Pollone, Raymond Quan, Eric Rochin, and Mazen Salfiti for always supporting me and my endeavors.

And finally, to my aunt, Helen Ho, who brought my family to the United States, and to my immediate family: my siblings William, Chris, and Phillippa; my dad, Youn; and my mom, Eileen. Thank you for sacrificing so much to ensure your children would have a brighter future.

Curries and Slow-Cooked Dishes

Alex Naitun ThawngNinheads the kitchen at Oaklands Burma Superstar. There, he makes curries by the stockpot.

To ensure no bits of onion scorch on the bottom of the pot during the process, he stirs the onions with a wok spatula fashioned with a long wooden handle, giving the spatula the effect of a paddle. Once the onions are soft, with most of their water cooked out, Nin builds up flavor in layers, starting with the garlic, following with the chicken, coconut milk, and fish sauce, and finishing with generous pinches of curry powder and cayenne. The curry is ready when bits of paprika-red oil rise to the surface, but it always tastes better when left to rest for a few hours. Ask Nin, who is from Myanmars Chin State, what hed do if he were making curry for himself and the answer is easy: bump up the heat with a lot of Thai chiles.

Compared with spicy and elaborate Indian and Thai curries, Burmese curries are mildly spiced, deeply savory, and easy to make at home. Whether featuring meat, fish, or vegetables, the curries all share the same rhythm and bass. Start by sweating the onions or shallots in oil and then add garlic and sometimes ginger and lemongrass (especially if the curry features fish or shrimp). Nearly all of the curries use turmeric and some sort of ground chile to spice things up. All of this is cooked gently until the oil returns, by rising back to the surface.

The oil used in Burmese cooking is neutral in flavor, but its the quantity of oil that gets people talking. Theres a reason the Burmese go heavy on oil. Traditionally, access to refrigeration was limited, so sealing off a curry with a layer of oil was a way to protect it from contaminants. Starting a curry with oil also makes the onions and garlic cook more evenly without as much risk of burning them. And in dishes like , the oil used to fry the onions is used again later to flavor the dish. Today, many urban Burmese cook with less oil or ladle extra oil out of the pot after cooking the onions. The recipes in this book offer middle ground, using more oil than is typical in America but less oil than would be traditional in Myanmar.