Table of Contents

Guide

Copyright 2016 by Stephen Harding

Originally published in Great Britain as Voyage to Oblivion by Amberley Publishing in 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth, 3rd floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Designed by Amnet Systems

Set in 10 point Palatino LT Std by Perseus Books

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Harding, Stephen, 1952- author.

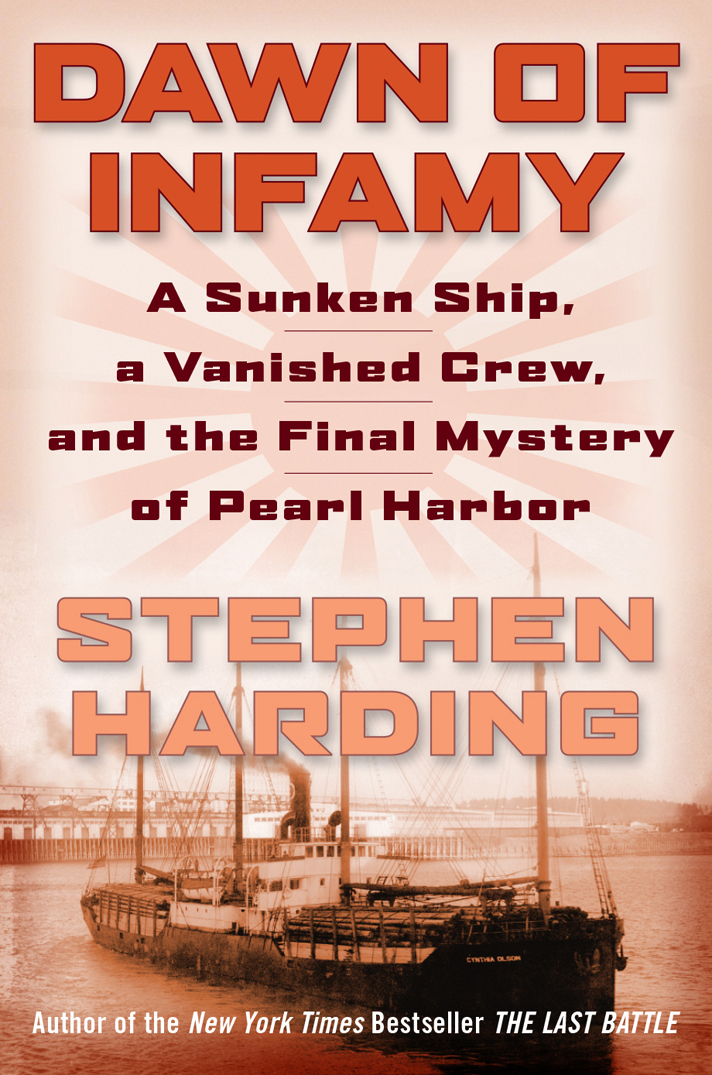

Title: Dawn of infamy: a sunken ship, a vanished crew, and the final mystery of Pearl Harbor / Stephen Harding.

Other titles: Voyage to oblivion

Description: Boston, MA: Da Capo Press, 2016. | Original title: Voyage to oblivion. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley, 2010. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016026005 (print) | LCCN 2016031133 (ebook) | ISBN 9780306825040 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 1939-1945Naval operationsSubmarine. | World War, 1939-1945Naval operations, Japanese. | Cargo shipsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Submarines (Ships)JapanHistory20th century. | Pearl Harbor (Hawaii), Attack on, 1941. | Cynthia Olson (Cargo ship)

Classification: LCC D783.7 .H38 2016 (print) | LCC D783.7 (ebook) | DDC 940.54/26dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016026005

Published by Da Capo Press

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

As always, for Mari

CONTENTS

Illustrations following

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidst the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

O, hear us when we cry to Thee

For those in peril on the sea!

And now, without having wearied my friends,

I hope, with detailed scientific accounts, theories,

or deductions, I will only say that I have

endeavored to tell just the story of the

adventure itself.

Joshua Slocum

ON THE AFTERNOON OF MONDAY, December 1, 1941, Captain Berthel Carlsen leaned over the bridge wing of the steamship Cynthia Olson and ordered deckhands to let go the mooring lines holding the small freighter to a pier in Seattle, Washington. Carlsen, a sixty-four-year-old master mariner, then ordered slow ahead on the engine-order telegraph. Minutes later, her single screw churning the waters of Elliot Bay, the twenty-two-year-old ship set out on the 135-mile passage up Puget Sound, bound for the Pacific Ocean.

It was a familiar route for both Carlsen and his vessel. Though the ship had sailed the Atlantic and Caribbean in her youth, for the first seven months of 1941, Cynthia Olson had plied the waters of the West Coast as a lumber carrier. Homeported in San Francisco, she made regular calls at Olympia, Tacoma, and other Pacific Northwest ports, often with Carlsen in command. Once her decks were covered with stacks of freshly sawn timber and her holds filled with massive rolls of newsprint, shed sail for Oakland, Los Angeles, or San Diego. It was a fairly mundane routine, but one that had proven dependably profitable for her owner, San Franciscos Oliver J. Olson Steamship Company.

But that routine changed abruptly in early August, when the Olson Company signed a contract with the U.S. Army. That service had launched a hurried military construction effort in Hawaii in response to the increasing threat of war in the Pacific, and Cynthia Olson and ships like her were needed to haul the timber that would become the barracks, warehouses, and aircraft hangars of what the War Department hoped would be a newly invigorated Hawaii-defense force.

Cynthia Olson had embarked on her first timber-hauling passage to Pearl Harbor on August 22, completing each leg of the trip in nine and a half days under the command of Captain P. C. Johnson. A second trip, in late September and early October, worked out equally well, and on November 18, the Army chartered the vessel outright. Now, on the first day of December, she was setting out again, with Carlsen as a last-minute substitute for an ailing Johnson. Sharing the bridge was First Mate William Buchtele, himself a last-minute replacement, and together the two men hoped to better the previous total passage time by at least a day.

What neither mariner could know was that their ship and the thirty-five men aboard her were embarking on their final voyage. Even as Cynthia Olson chugged slowly toward the sea, events were unfolding that would pit the ship and her crew against a deadly foe, mark the beginning of a new front in a global conflict, and spark one of the most enduring nautical mysteries of World War II.

THE VESSEL BERTHEL CARLSEN AND his ill-fated crew took to sea that day in early December 1941 had started life a continent away, and by the time she set out on her last voyage, shed already spent some two decades plying both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It hadnt been an easy life, and she was starting to show her age.

A product of Wisconsins Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company, the vessel was laid down in the late summer of 1918 as Coquina, one of some 331 oceangoing freighters built for the U.S. Shipping Board (USSB)

The USSB and, after September 1917, a subordinate agency called the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC), ultimately awarded contracts for the construction of 346 The ships were of six variants, which differed slightly in gross tonnage and overall length. Each variant was given a type number, with the thirty-three examples ultimately manufactured by Manitowoc Shipbuilding being designated Design 1044.

These solidly built and dependable craft had an overall length of 251 feet, a beam of 43 feet 6 inches, and a loaded draft of 23 feet. Each ship weighed in at 3,400 deadweight, 2,800 gross, and approximately 1,280 net tons. Though they differed in small structural details, all featured the standard Laker three-island silhouetteraised focsle and poop deck, and a large amidships deckhouse with a single funnel set just aft of the bridge. The vessels had two large cargo holds, one forward and one aft of the deckhouse, each of which was accessed through two hatches, one directly behind the other. Each hold was served by two sets of twin booms. Two of the booms for each hold were fixed to kingposts, one set of which was attached to the forward part of the deckhouse and one set to the aft. The other two booms for each hold were attached to taller masts: one set into the focsle and one into the poop. Each boom had its own dedicated winch.

The Design 1044 Lakers were built with cellular double bottoms, The aft two-thirds of the boat deck, one level higher, were open to the elements and housed two twenty-four-foot wooden lifeboats (each capable of embarking thirty-six people), a sixteen-foot workboat, and davits for each. The forward part of the boat deck was taken up by the structure housing the staterooms for the captain and first officer, each of whom had direct access to the boat deck. Directly above these two cabins was the Lakers wheelhouse, which incorporated two bridge wings, a chart room, and the captains small day cabin.

Next page