Autumn: oil on canvas (1573) by Giuseppe Arcimboldo

{Lauros/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library (BAL)}

I dedicate this book to Chloe, my ancient Jack Russell. Much of the book was planned during our daily walks together. I am also indebted to my nieces Charlotte and Sarah for their valuable comments and corrections at the manuscript stage. Finally thanks to my wife Jean and daughter Bryony for putting up with me while I was writing the book and good luck to my son Martin who sensibly moved out before I started.

William Collins

an imprint of HarpercollinsPublishers

7785 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

Text Patrick Harding 2008

Illustrations/Photographs as per Picture credits on page 208

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Publisher: Myles Archibald

Editor: Charlotte Pover

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007284641

Ebook Edition JULY 2014 ISBN: 9780007596683

Version: 2014-06-13

Contents

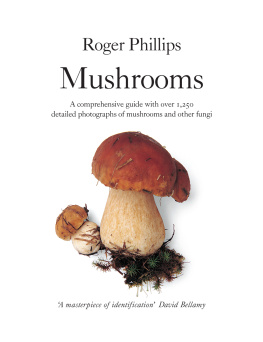

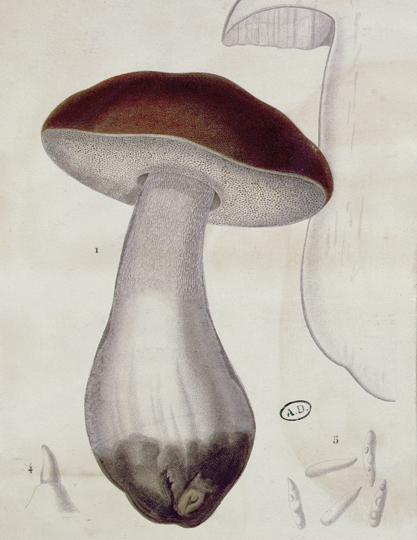

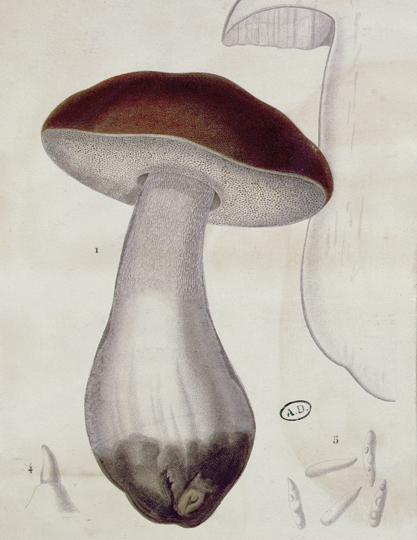

Boletus edulis (early 19th century) by Paul Louis Oudart

(Archives Charmet/BAL)

I n the autumn of 1981 I taught my first residential weekend course on Mushrooms and Toadstools. On the Friday evening the small group of participants joined me for a preprandial drink. It was not long before I discovered that each of them had a similar tale to tell. The stories all included accounts of the jaw-dropping response of family and colleagues when told of the reason for their weekend away. In those days very few shops stocked anything other than white cultivated mushrooms which were usually neatly displayed in blue cardboard punnets. Field and other wild mushrooms were largely left alone.

As for those people who collected and ate toadstools, they were considered to be either wildly eccentric or of European extraction. I was placed in the former category when, in 1983, The Guardian Diary section included a preview of seasonal entertainments offered by the Youth Hostel Association:

Curiosities like a voodoo evening at Boggle Hole in Robin Hoods Bay are available, or an Esperanto weekend in the Peak District. First prize for an offbeat break, though, must go to the fungus foray based at Edale on the weekend of October 7th9th. For an extra 6 you can join mycologist Dr Patrick Harding collecting blewits, chanterelles and boletus [sic] edulis and consuming them in a fungus feast.

Five years later I was invited to teach a mushroom course on behalf of Cambridge Universitys Adult Education Department, based at Madingley Hall. The silver service dinner on the Friday was preceded by a resonant gong and full Latin grace. Prior to the coffee, the warden addressed the assembled company:

Welcome to Madingley and to a fascinating range of weekend courses. Unexplored Mozart will take place in the Saloon; those Reading Greek will be in the Library while Mushrooms and Toadstools will be

Her voice was drowned by the rising tide of laughter from the musicians and linguists as I tried to appear invisible. By the Saturday evening I had recovered my composure and made my own announcement before the coffee was served:

Those of you studying Mozart and Greek are more than welcome to pay a brief visit to the board room, where you might be interested to see what those on the Mushroom course have been up to.

Spread across eight tables were scores of labelled specimens collected on our field trip. Two years later, when the course was repeated, I was delighted to welcome among the course members two from the Greek and three from the Mozart group. Twenty years on and the mushroom course is still running. It is heavily oversubscribed.

Mushroom hunters of European extraction included Polish immigrants who had settled in Britain during and immediately after World War II. Collecting and eating fungi is an important part of Polish culture and those in the vanguard of the more recent influx must have been pleasantly surprised by the lack of local competition when it came to mushroom hunting. A Polish dish traditionally served on Christmas Eve includes Boletus edulis in the list of ingredients.

Old English books about cookery and mushrooms mentioned Boletus edulis under its local name of penny bun. This moniker arose on account of the likeness of the pale-brown, slightly sticky, convex cap to a product displayed in many bakers and which had originally sold for just one (old) penny. In the years following World War II the bakers penny bun lost its fight against inflation while the mushroom lost the battle to keep its old English name. As British cooks looked for inspiration from French cuisine so the writers of cookery books anglicised the French name for the fungus Cpe and penny bun became known as cep.

British cooks have rarely suffered from a shortage of recipe books; if anything the problem has been more one of surfeit rather than deficiency. The same cannot be said of books about mushrooms and toadstools; although like buses, after a long wait, several turned up at once. Lack of interest in edible mushrooms has long bordered on a phobia in Britain; a condition not helped by a paucity of non-technical books aimed at the general public.

Mordecai Cooke did his best in Victorian times with publications such as British Edible Fungi How to Distinguish and to Cook Them. The British Governments attempts to encourage fungal foraging, especially during times of food shortage, resulted in Edible and Poisonous Fungi Bulletin No 23 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, first published in 1910. This slim booklet described just 19 edible varieties and nine poisonous ones. The remaining stock of the 1945 edition was destroyed by a German incendiary bomb, which may have been a blessing in disguise given that one of the species included in the edible section has since proved to be poisonous, albeit it to a minority of the population.

In the 1960s Findlays Wayside and Woodland Fungi included some illustrations by Beatrix Potter (see ), but the book was not aimed at those with a culinary interest in the subject. Richard Mabeys ground-breaking Food for Free, first published in 1972, included a section on edible fungi. Three years later Jane Grigson produced her culinary classic, The Mushroom Feast