MUSHROOMS

MUSHROOMS

A Natural and Cultural History

Nicholas P. Money

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2017

Copyright Nicholas P. Money 2017

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780237916

Contents

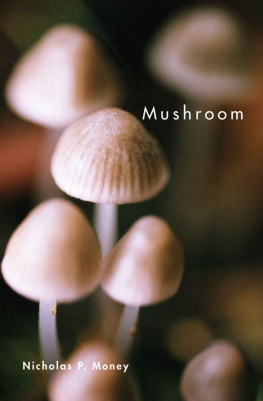

Pair of fruit bodies of a gilled mushroom.

Introduction

Soft umbrellas

of the underworld

push up

through beaded moss,

spokes rusted with spores,

eager for wind

CHRISTINE BOYKA KLUGE, Toadstools

M ushrooms are loved, despised, feared and misunderstood. This is true of many other groups of organisms sharks are loved, despised and so on but the fruit bodies of fungi occupy a special place in human consciousness, embedded in childhood through fairy tales, films and video games. Widespread familiarity with mushrooms provides an audience for the study of fungi, or mycology, but a great deal of remedial work is necessary to counter misconceptions about these fascinating organisms. This book introduces mushroom mythology and science, the history of our interactions with these fungi, and the ways in which humans use mushrooms as food, medicine and recreational drugs. The natural history is supplemented with profiles of the mycologists who advanced the study of the fungi. As paragons of eccentricity, these individuals are peerless.

A mushroom is not a self-contained organism, like a jellyfish, for example. It is a reproductive organ produced by a colony, or mycelium, which grows in soil or rotting wood. For convenience, we use the term mushroom rather than mushroom-forming fungus to describe the whole organism, although this is a bit like using a photograph of a large pair of testicles to represent an elephant. Describing the fungi that form mushrooms as microorganisms may seem strange given the macroscopic nature of their fruit bodies. It is justified, however, because mushrooms tend to be short-lived compared with the continuous feeding activities of the microscopic filaments of their supporting mycelia. There is no ambiguity in the inclusion of other fungi within the purview of microbiology, because they do not form mushrooms, and go unnoticed without magnification.

Mushrooms are produced by 16,000 species of fungi classified as basidiomycetes. They grow on every continent, thriving in wet conditions, breaking down organic matter and recycling soil nutrients. Mushrooms also support trees and shrubs through root connections called mycorrhizas, in tropical, temperate and boreal ecosystems. An equivalent number of basidiomycetes grow as budding yeasts, and rusts and smuts that attack plants. The basidiomycetes are one of a handful of major categories of fungi. The others include ascomycetes, pin moulds that spoil food, and a spectacular range of aquatic fungi whose spores swim like animal sperm cells. More than 70,000 species of fungi have been described and those awaiting discovery probably run into the millions. This mismatch between known and unknown results from the astonishing richness of microscopic organisms, our inability to grow most of them in Petri dishes, and significant problems with sorting out species of fungi. The straightforward differences that enable us to discriminate between foxes and rabbits do not apply to mushrooms, and we are left with many species that may or may not be separate entities.

Mushrooms have been the subject of superstition and folklore for centuries and they were objects of worship by ancient civilizations. The association between mushrooms and varied fancies is explained, in part, by their strangeness. The overnight appearance of mushrooms is a startling phenomenon and the growth of some species in fairy rings seems very peculiar until one understands how they grow. Other superstitions, including their associations with witchcraft, derive from the poisonous and hallucinogenic natures of a small number of species.

Mid-16th-century woodcut of mushrooms with a pair of snakes and a snail.

Rational approaches to the study of mushrooms began with the work of Renaissance botanists in the sixteenth century, and fungi were presented in the great European herbals of this era. The first sensible guide to mushroom edibility was published in 1675, and mushroom colonies were featured in the work of the early microscopists. At this time, mushrooms were regarded as a peculiar branch of the animal kingdom, something akin to sponges or worms. This is interesting given current molecular evidence of shared ancestry between fungi and animals. In the eighteenth century most authorities viewed fungi as primitive plants, which explains why mycology is treated as a branch of botany when zoology is a more logical fit for these animal relatives.

Pier Antonio Micheli was the first naturalist to conduct experiments on mushrooms, and his Nova plantarum genera, published in 1729, is a masterpiece of early scientific investigation. He died from pleurisy in 1737, contracted during a mushroom-collecting trip, and is remembered as the father of mycology. Micheli was the first of a remarkable succession of eccentrics who have dedicated their lives to the study of mushrooms. Foremost among the historical figures is A. H. Reginald Buller, a British-born scientist who was a founding member of the science faculty at the University of Manitoba in the early twentieth century. He lived in hotels in Winnipeg for forty years and crossed the Atlantic each summer to work at Kew. A lifelong bachelor, with singular dedication to mycology, Buller walked to work with horse blinders strapped to his head to preserve his light sensitivity for experiments on bioluminescent mushrooms. He was attacked by an eagle while collecting mushrooms with students, and wrote dreadful poems about fungi in his leisure hours. His American counterpart, Curtis Gates Lloyd, was similarly obsessed. This wealthy Cincinnati bachelor published a mycological journal for 28 years and used his uncontested editorials to ridicule the work of prominent academics with whom he warred.

Lloyds peculiarities are eclipsed, perhaps, by the work of Captain Charles McIlvaine, veteran of the American Civil War, novelist and poet. In pursuit of the greatest mushroom guide in history, McIlvaine volunteered as his own experimental animal, testing the edibility of every mushroom described in his One Thousand American Fungi (1900). This enormous tome is testament to a mans triumph over unappetizing stews and digestive discomfort. The peculiarities of women mycologists pale in comparison with these gentlemen of the science, which is not surprising given the greater tolerance of male eccentricity within society.

Through the endeavours of Buller and his contemporaries, we learned that mushrooms were far stranger and much more interesting than anything imagined in mycological folklore. Other mycologists were satisfied with identifying fungi, but Buller revealed the beauty of the microscopic activity beneath mushroom caps that allow single fruit bodies to release billions of spores in a day. Multiplied by the immense numbers of fruit bodies in the worlds forests, this astonishing fecundity mists the atmosphere with millions of tons of spores, causing misery for asthmatics, affecting atmospheric chemistry and even influencing rainfall patterns.