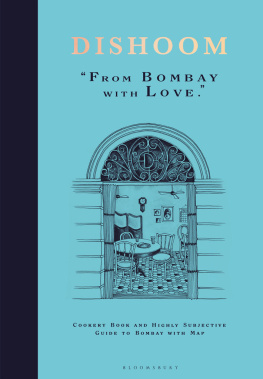

This book is dedicated to the late, great Rashmi Thakrar who passed away, too soon, in 2017. He was Shamils father, Kavis uncle and the first Dishoom person that Naved ever met. He was (until the very end) our most joyful cheerleader, and tireless finder-in-chief of obscure nuggets to turn into fully formed ideas. Hes the reason why Dishoom is so full of stories.

He believed that for something to truly succeed it must have a little poetry at the heart of it.

He also believed in reincarnation. Wed like to think that he is somewhere reading this dedication and diving into this book with delight.

CONTENTS

*Novices to Indian cookery, seek enlightenment here.

WELCOME TO BOMBAY

First impressions

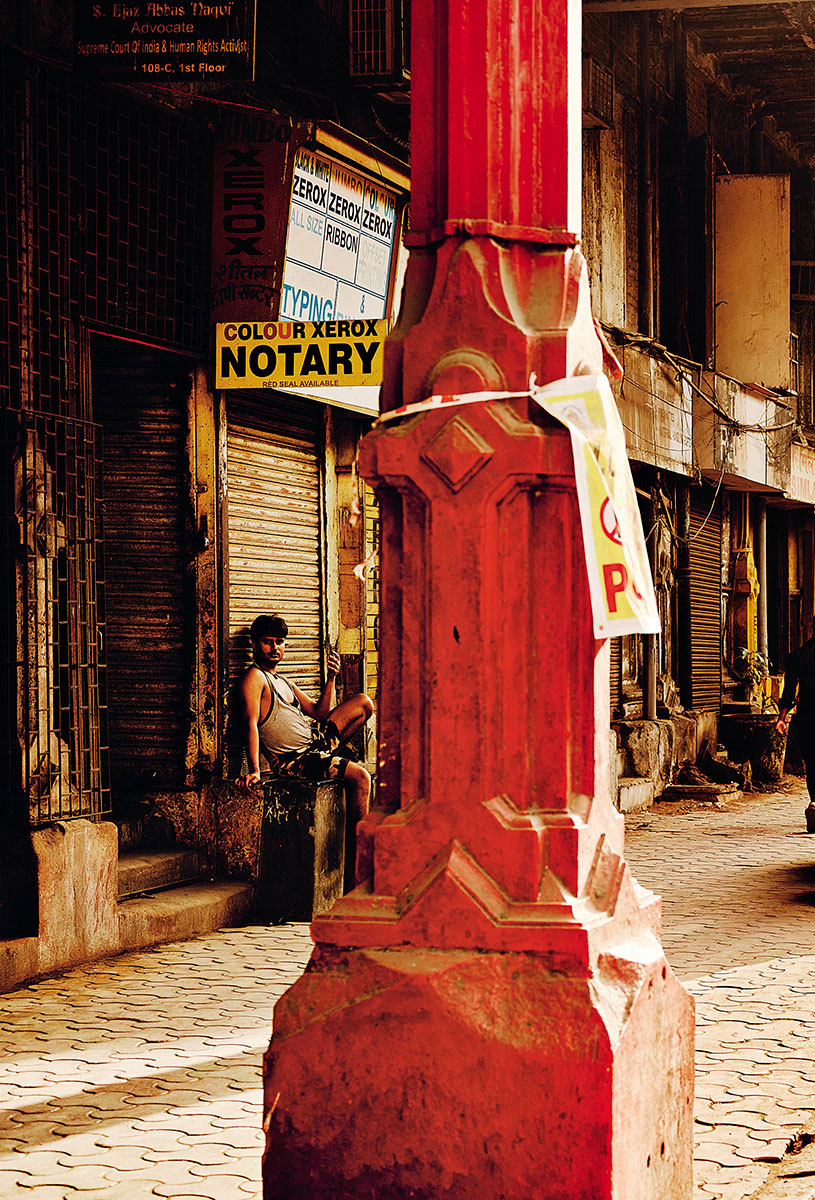

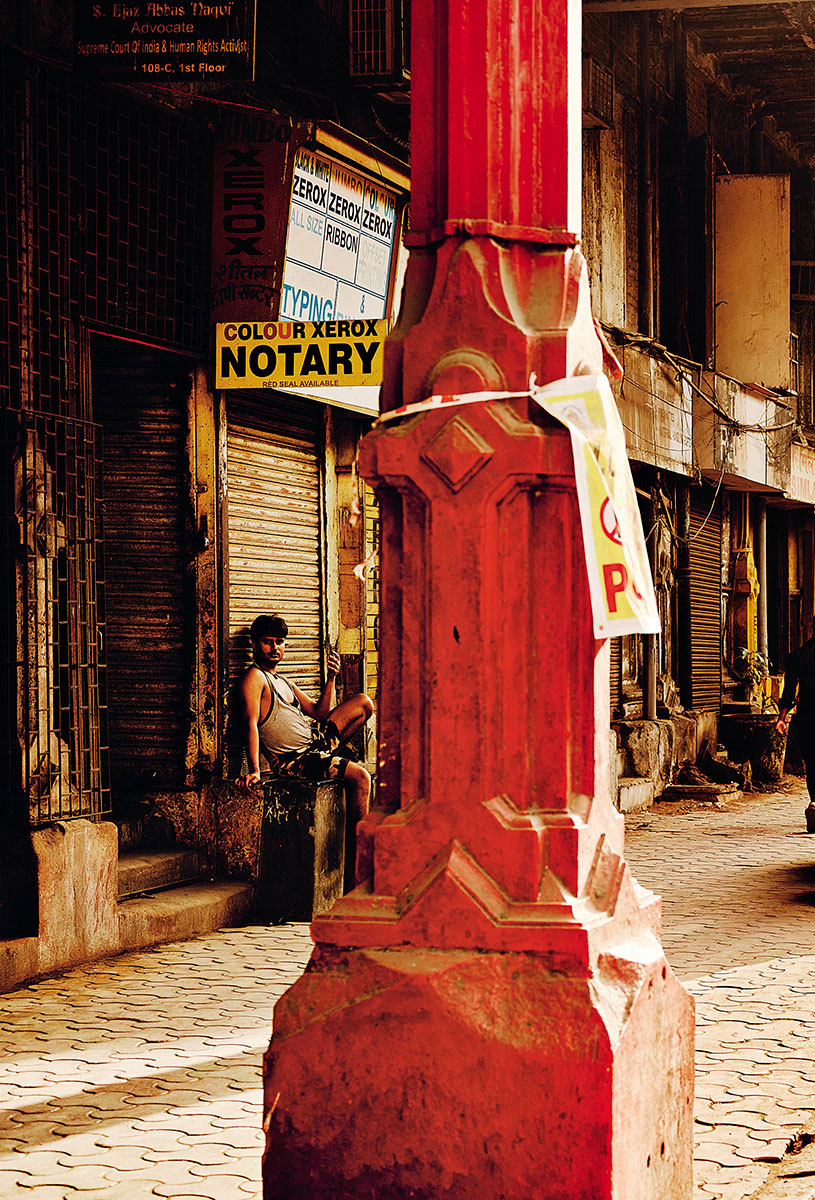

You may not find Bombay an easy sort of place. At least, not to begin with.

As you step off the plane, you first feel the heat, then a ripe waft of warm air. Then, an unfeasibly new, shiny airport and an invariably old, surly customs official. After your perfectly good papers have been shuffled, scrutinised and shuffled again, you head into town, perhaps in one of the noisy little black and yellow 1960s design Fiats that still function as part of the swarm of taxis in Bombay.

Next, as an appropriate introduction to the rhythms of the city, you experience the traffic. For at least a little of the time, your sweaty and smiling taxi-walla cheerfully weaves in and out of lorries and scooters, narrowly missing them. The rest of the time you and he are stuck, engine off, your arm resting on the hot metal window sill, sitting in the jaded torpor of standstill hooting traffic. Perhaps you are on a flyover, able to peer into the open windows of the little flats on either side. You will have noticed that there are people everywhere, crowded onto motorbikes, into cars, onto the streets.

More than likely, you will eventually arrive at your destination. If youre coming to south Bombay, you will probably travel past high-rises, permanent makeshift slums, crumbling old houses, a brand new sea-link flyover and an Aston Martin dealership, to arrive somewhere near the bottom of the pendant of reclaimed land that is the city.

By now, you may have an initial impression of Bombay. Its a crowded place, of course. Glass and steel alternates with corrugated iron and then gives way to fading Art Deco and wild, slightly oriental Gothic. Its not really the same as the rest of India. Its somewhat monochromatic, with less of the colour that people seem to associate with the country. It is clearly a city of massive and closely juxtaposed extremes.

However, as you spend more time in Bombay you might begin to see past your first impressions, past the crowds, past the extremes and into the layers: Portuguese then British colonial rule, massive inward migration from both land and sea, development of enterprise and wealth, myriad and unexpected ethnicities, religions, cultures and languages. Its certainly the biggest, fastest, densest and richest city of India. But it is also the most cosmopolitan; it is startlingly full of accumulated difference. In a way, it seems that this accumulated difference, and its complete internalisation, has become the nature of the city itself. So many different voices from so many different places telling so many different stories joined together to become Bombay.

And then, gradually, you discover the simple joy of morning chai and omelette at Kyani & Co., of dawdling in Horniman Circle on a lazy morning, of eating your fill on Mohammed Ali Road, of strolling on the sands at Chowpatty at sunset and of taking the air at Nariman Point at night.

Once you have found your places of refuge, Bombay first becomes human and then without you noticing exactly when it completes the seduction and becomes delightful.

Meet your hosts at the charming Irani caf, Koolar & Co.

For me, the Irani cafs are a significant part of this seduction. Once liberally sprinkled across the city, only twenty-five or so remain, all of them old, comfortable and worn. All who know them well seem to have fond memories of them as places for bunking off school, or debating politics and philosophy with the idealistic energy of youth, or for escaping, deeply, into a book, all accompanied by chai. The Irani cafs were places for growing up, and for growing old, whoever you were.

In the course of your time here in the city, youll get to know these cafs and their ramshackle charm. Youll become familiar with their proprietors (invariably kindly and eccentric uncles or aunties), their food and, of course, their sweet milky chai. Might I suggest that you start in Koolar & Co.? This little caf occupies a narrow wedge of a street corner on Kings Circle up in Matunga, which is on the way to south Bombay. Amir-bhai is the owner and his family have had the caf since 1932. He is genial and quirky, like his caf. He is also generous in sharing his reminiscences over a plate of tasty but slightly odd honey half-fry eggs (eggs only slightly fried and drizzled with honey), which Ive never eaten anywhere but here.

Koolar & Co. has a specific importance for me. Not far away is a small ground-floor flat in an unremarkable building, where my mother and I spent a few months of my very early life. My family had been thrown out of our home on another continent, and Bombay was our refuge when we had nowhere else to go. We actually celebrated my first birthday here in Koolar & Co. and apparently we had a little cake. This would certainly be a memory I would lovingly treasure if I had it.

Meanwhile my father was getting our papers in order so that we could join him in London. Although we eventually settled there, I often returned to Bombay, and to that little flat. I used to stay with my grandmother (Baa), who had an enormous love for the city. My memories of that flat are vivid. If I close my eyes, I can still see our little blue Formica-topped dining table, with the crackling boxy Grundig radio that my grandfather (Dada) used to listen to intently, next to the little toaster that toasted one side at a time.

Without Baas influence, my cousin Kavi (also her grandson) and I literally wouldnt be doing what were doing at Dishoom. We both have distinct memories of being in Bombay with her. At Chowpatty or Crawford Market, or strolling up to Nariman Point at sunset with my grandfather, who could walk endlessly. Sadly, Baa and Dada are both no more, but a memory that I treasure lovingly is the utterly unselfconscious, wide grin on Baas face when she ate a kala khatta gola ice at our pop-up on Londons South Bank back in 2011. Even as she was in her eighties, she used to love showing off Dishoom to her old friends from Bombay. When she did so, it made my heart sing.