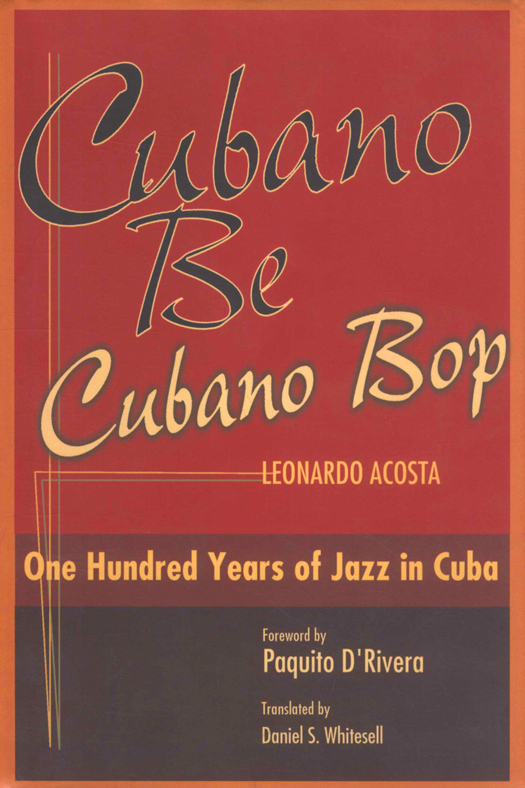

2003 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Copy editor: John Raymond

Designer: Brian Barth

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Acosta, Leonardo.

[Races del jazz latino. English]

Cubano be, cubano bop : one hundred years of jazz in Cuba / Leonardo Acosta ; translated by Daniel S. Whitesell.

p. cm.

Translation of the original Spanish edition (Barranquilla, Colombia, c2001).

ISBN 1-58834-147-X (alk. paper)

1. JazzCubaHistory and criticism. I. Title.

ML3509.C88A2713 2003

781.65097291dc21

2003041446

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the author. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually, or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-58834-547-9

v3.1

I t was one of those luminous nights in Havana in the early Sixties, when our little gang of Los Chicos del Jazz, cruising down Twenty-third Street, arrived at the nightclub La Gruta (The Grotto). We were going to listen to Free American Jazz, a group founded by pianist Mario Lagarde and saxophonist Eddy Torriente, two African Americans who had just established themselves in Cuba. It must surely have been Friday or Saturday, since the small club located in the basement of the La Rampa movie house was completely packed with jazz aficionados, or simply with curious people attracted by those musicians who had arrived from the mythical Forbidden North. The rest of the quartet consisted of drummer Pepe El Loco and, on the contrabass, the composer Julio Csar Fonseca, a picturesque character of the bohemian Havana nights.

Down in the grotto, when we finally cut through the crowd and smoke, we found Eddy El Americano, seated on one of the high stools at the bar with a very cold beer in front of him: Hey, Campen del Mundo! shouted the charming mulatto saxophonist, raising his frothy beer mug in the air. It was his signature salute to all those colleagues who came each evening to listen to his beat-up Conn alto sax, which he played in that old style inspired by his idol Paul Gonsalves.

Behind the bar, in the reduced space of the bandstand, and occupying Eddys place next to his compatriot at the piano, there was a young, skinny man wearing glasses, looking somewhat like Paul Desmond. Hanging from his neck was an enormous silver-plated baritone sax made in Czechoslovakia. Mario Lagarde counted off a medium bounce tempo and, following a brief introduction of Pepes Hi-Hat, the group began to play his composition La Gruta Blues. The first solo was taken by the saxophonist, who immediately caught our attention, mainly because with the exception of the few Gerry Mulligan, Serge Chaloff, or Harry Carney recordings that my father or Amadito Valds played at home, this was the first time that we heard a baritonist playing Be-Bop lines live! At that time I was almost a child and was fascinated with the musical language of that skinny guy with the enormous shiny saxophone that was none other than Leonardo Acosta.

You are Titos son! How is your old man doing? I havent seen him in years, he said enthusiastically when I went to greet him at the end of the set. This was the beginning of a solid friendship that has lasted till today, and from then on Ive deeply admired Leonardos musical and literary labor. Along with Camille Saint-Sens, Artie Shaw, Nicols Slonimsky, and a few others, Leonardo Acosta belongs to that select group of musicians who also possess the ability to communicate through the written word. Thats why Ive always thought he was the most appropriate person to tell the story of what happened in the past hundred years of jazz music on our island.

I hope youll enjoy this new book of Leonardos (which reads like a novel, as Nat Chediak would say) as much as I enjoyed his baritone solo on that far away evening in Havana at La Gruta Club.

P AQUITO DR IVERA

New York

November 2002

T he book you are about to read is the product of thirty years of research and active participation in the world of jazz in Havana by a highly distinguished Cuban musician, musicologist, writer, and literary critic. Leonardo Acosta was born in Havana in 1933 into an artistic family. His father was a notable graphic artist and his paternal uncle a major Cuban poet. Acosta undertook formal music studies from an early age and began a career in architecture, which he gave up quickly to dedicate himself to playing the love of his life, jazz, as well as Cuban popular music. In the 1950s he played saxophone (tenor, alto, and occasionally baritone) with all the important jazz groups in Cuba including the noted Armando Romeu orchestra.

In 1955 Acosta fulfilled a dream of his youth, traveling to New York for several months, where he was able to listen firsthand to his favorite jazz musicians: Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, Phil Woods, Dinah Washington, Terry Gibbs, Dave Brubeck, Philly Jo Jones, Miles Davis, George Shearing but, in particular, Dr. Billy Taylor, with whom he talked at length about jazz on several occasions.

Upon returning to Havana, Acosta devoted himself to playing jazz but, in a demonstration of his versatility, joined for a while the Beny Mor band, at that time the premier Afro-Cuban dance band on the island, in which he and another jazz player, Jos Chombo Silva, were the two tenor saxophonists. Then, in 1958, Acosta and a few friends, among them Frank Emilio Flynn, Cachato Lpez, Gustavo Mas, and Walfredo de los Reyes Jr., founded the Club Cubano de Jazz. The CCJ set out to bring, for the first time and on a systematic basis, notable jazz musicians from the United States to perform in Cuba. For the next three years the CCJ sponsored jazz concerts in Havana featuring invited U.S. jazz musicians such as Zoot Sims, Stan Getz, Philly Jo Jones, and others. The CCJ also organized jam sessions with Sarah Vaughan and her trio and with the American musicians that accompanied Nat King Cole and Dorothy Dandridge on their visits to Cuba. The CCJ fostered an interchange between jazz musicians in Cuba and the United States and provided an important stimulus to the development of jazz in Cuba.

In the 1960s and 1970s Acosta worked indefatigably as a jazz musician, as a leader of several jazz ensembles, and as a promoter of jazz performances in Cuba. He was the intellectual leader of a small nucleus of Cuban jazz veterans who consolidated Cubas distinct jazz tradition and nurtured and inspired the new generation, the likes of Chucho Valds and Paquito DRivera. Acosta also participated in an experimental modern music ensemble with distinguished musicians such as Leo Brouwer, Pablo Milans, and Emiliano Salvador, and wrote the soundtracks for several documentaries and movies during this period.