Prologue

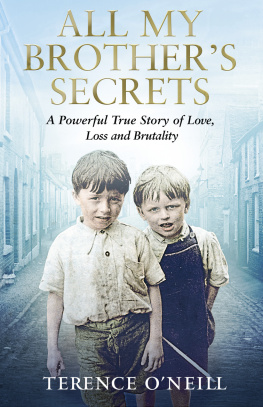

I m an ordinary man; maybe some people would call me an insignificant one. I dont mind if they do. I know who I am.

I like order in my life; routine is important to me. Its that everyday sameness that has at last given me peace. Each morning before I leave my house I make my bed the way I was made to do as a boy: sheets pulled up tightly and the corners tucked in neatly. I wash my mug and plate and place them in the cupboard over the sink. And when I return home from work its my practice to take a shower, pull on jeans and a T-shirt, put away my work clothes and make a mug of tea just in time to watch the evening news.

But it was that very routine that destroyed the calmness in my life. The calmness that had taken me so many years to achieve disappeared on a February night when I turned on my television and heard the words abuse, rape and cover-up.

It was the newsreader informing viewers that the dark side of Jersey had been exposed.

Suddenly the screen was filled with the blown-up photograph of a large granite building; a building that I, with a rising feeling of nausea, immediately recognised Haut de la Garenne. Then the picture changed to show dogs on leashes held by white-coated handlers. The police had brought in sniffer dogs.

The remains of a child had been found, they said.

Only one? I thought to myself.

The camera moved on to a young reporter standing in the grounds who, with a sympathetic expression on his face and a microphone in his hand, was addressing his unseen audience of millions.

The secrets and lies of Jersey have finally come to light, he told us. What has been revealed has shocked the residents of an island known not just for its beauty, but also for its tranquillity and lack of crime.

Behind me, the reporters voice continued, is the childrens home where, over a period of nearly ten decades, more than a thousand youngsters have been fed, clothed and housed by the charity of Jerseys government.

Some were orphans, some were abandoned, others had been taken into care, but whatever the reason they had been placed in this grey Victorian building they all had one thing in common vulnerability. They, more than any others, were in need of love, understanding and protection. However, here that was denied them; for it was in this institution that their childhood lost its final struggle to exist.

The picture changed again and we were back with the newsreader, who informed us that the complaints, the allegations and the whispered stories that had rebounded over Jersey for nearly half a century had finally come to be investigated. Those rumours of rape, torture and even worse had now become shocking accusations.

He said the police feared there might be more human remains buried in six other suspect sites the dogs had found. In the cellars underneath the main building a room showed signs that it had been used as a torture chamber. Over a hundred adults, who had once been the children of Haut de la Garenne, had made accusation after accusation to Jerseys police of the abuse that allegedly had taken place there. In fact, one of those people was in the studio.

The camera swung round to focus on an elderly couple that the newsreader was about to interview. The husband, a decade or more older than me, was in a wheelchair. His wife sat next to him, her hand resting lightly on his arm. I could clearly see the tremor in his age-spotted hands as he prepared himself for the questions he knew were going to be put to him.

His first answer was bleak and simple. Yes, I was there, he said. I was at that place.

As the words left his mouth, his chin trembled and tears leaked from his eyes. And putting my hand to my face I found corresponding tears had dampened my cheeks; the tears of the smooth-skinned boy I had once been.

And the only thought filling my head then was: and so was I.

O nce the initial shock of hearing the words Haut de la Garenne had faded I tried to make my mind travel back in time and revisit the past. I knew that I wouldnt be able to leave my childhood memories buried any longer. The relentless surge of interest in Jerseys secrets would make sure of that. But Id kept my thoughts so carefully concealed for so long that they refused to obey me. I couldnt think about either the granite building that dominated the news or the orphanage, run by the nuns, which I had been sent to first. Not yet, they said to me, not yet. Instead they bypassed that time and went straight back to that last summer I spent with my family. The summer before they took us away.

Six of us my mother, Stanley (her current man), my two brothers, me, and the latest addition to our family, a baby sister lived in Devonshire Place in St Helier, the capital of Jersey. It was an unremarkable area made up of terraced houses, a couple of pubs and a few corner shops. A place where families lived, children played and women stood on their doorsteps, cigarette smoke swirling around their heads, swapping gossip with the neighbours. A street like many others; certainly there was nothing unusual about it, but in summer, when the sun shone on the pastel-painted houses, I thought it was pretty. And it was my home.

We all lived in three rooms on the top floor of one of those houses. Directly beneath the uninsulated roof, they were cold and draughty in winter but stuffy and airless in summer.

I was the middle boy. My elder brother John, with his spiky blond hair that refused to obey his brush however much he dampened it, his wide impish grin and his infectious laugh, was eight, three years older than me.

Davie, the youngest, with his round little stomach and chubby legs and indentations on either side of his mouth, was all curves and dimples. He had just learnt to talk in partial sentences and with a wide grin on his pink-cheeked face claimed our attention by chattering to us as fast as he could. He followed John and me around our rooms, stumbling in his haste, his legs slightly bowed, for at three he was still in bulky towelling nappies; not so much because he couldnt tell one of us when he wanted a wee but because our mother didnt want to climb down three flights of stairs to the outside lavatory with him. Even sitting him on a potty regularly appeared to take too much effort. Davie often remained all day in his damp nappy until his eight-year-old brother came home from school and changed it.

I looked like neither of them. I had a slight frame, fine dark hair and grey eyes that peered myopically at the world.

John told me that he knew Stanley wasnt his father because he dimly remembered the time when he first came to live with Gloria. We always called her Gloria never mum.

You arrived soon after, he told me. So I guess Stanleys your dad but hes not Davies.

How do you know? I asked in a puzzled voice, but John didnt answer me then.

Years later he told me that hed overheard Stanley shouting at Gloria, asking her who the babys father was, when he found out that she was pregnant with Davie. Certainly with his light brown hair and round face, he bore no resemblance to the dark-haired, olive-skinned Stanley, but Gloria insisted he could only be his. Denise was dark like Stanley but it was hard to tell what her baby features would be like when she grew up.

Another reason I always believed that Stanley was my father was that although he was mild-mannered and never said an unpleasant word to my brothers, it was me he seemed to single out for attention. Sometimes it was just a warm smile and a hand brushed lightly across my head. Occasionally, when Gloria was out of hearing range, he would fumble in his pocket, draw out a few coins and place them quickly in my hand.

Buy yourself some sweets, lad, he would whisper to me and I knew to hide the money away from Glorias sharp gaze. He even on rare occasions took me down to the pier on the small wooden cart attached to his bicycle and treated me to an ice-cream. But apart from those few encounters he was rarely seen, nor did he involve himself with any of us.