Yotam Ottolenghi is a cookery writer and chef-patron of the Ottolenghi delis and NOPI restaurant. He writes a weekly column in the Guardians Weekend magazine and has published four bestselling cookbooks: PLENTY and PLENTY MORE (his collection of vegetarian recipes) and, co-authored with Sami Tamimi, OTTOLENGHI: THE COOKBOOK and JERUSALEM. Yotam has made two Mediterranean Feasts series for More 4, along with a BBC4 documentary, Jerusalem on a Plate.

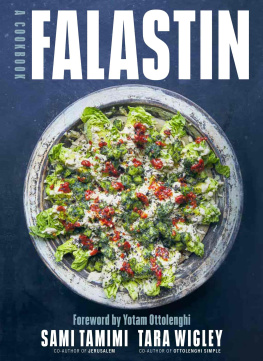

Sami Tamimis intimate engagement with food started at a tender age, whilst watching his mother prepare Palestinian delicacies at their home within the walls of Arab East Jerusalem. His first job was as a commis chef at the Mount Zion hotel in the city. He thereafter investigated some of his culinary passions, including the food of Yemen, Morocco, Egypt, Persia and even the Eastern European Jewish communities. In 1997 he moved from Tel Aviv to London to work at Baker and Spice, creating a unique traiteur section with the strong identifiable flavours of the Middle East. In 2002 he teamed up with Yotam to open Ottolenghi.

Ottolenghi

The interaction

One thing immediately evident at Ottolenghi is that you often see the chefs bringing up trays and plates heavily piled with their creations. It is a source of pride for them and for us to see a customer smile, look closely, and then gasp and give them a huge compliment. So many chefs miss out on this kind of immediate response from the diner the reaction that leads to a leisurely chat about food.

This communication is essential to our efforts to knock down the dividing walls that characterise so many food experiences today. When was the last time you went shopping for food and actually talked to the person who made it? In a restaurant? In a supermarket? It doesnt happen very often. So at Ottolenghi we are simulating a domestic food conversation in a public, urban surrounding.

The space

When you sit down to eat, it is as close as it gets to a domestic experience. The communal dining reinforces a cosy, sharing, family atmosphere. What you get is a taste of entering your mothers or grandmothers mythical kitchen, whether real or fictitious. Chefs and waiters participate, with the customer, in an intimate moment revolving around food like a big table in the centre of a busy kitchen.

But its not only the way you sit, it is also what surrounds you. In Ottolenghi you will always find fresh produce, the ingredients that have gone into your food, stored somewhere where you can see them. The shelves are stacked high with fruit and vegetables from the market. A half-empty box of swede might sit next to a mother with a baby in a buggy, until one of us comes upstairs and takes the vegetable down to the kitchen to cook.

The display

Once the food is on the counter, we try to limit the distance between it and the diner. We keep refrigeration to a minimum. Of course, chilling what we eat is sometimes necessary, but chilled food isnt something wed naturally want to eat (barring ice cream and a few other exceptions). Most dishes come into their own only at room temperature or warm. It is a chemical fact. This is especially true with cakes and pastries.

Our customers

Not many traditional hierarchies or clear-cut divisions exist in the Ottolenghi experience. You find sweet alongside savoury, hot with cold; a tray of freshly baked cakes might sit next to a scrumptious array of salads, a bowl of giant meringues or a crate of tomatoes from the market. It is an air of generosity, mild chaos and lots of culinary activity that greets customers as they come in: food being presented, replaced, sold; dishes changed, trays wiped clean, the counter rearranged; lots of other people chattering and queuing.

It is this relaxed atmosphere that we strive to maintain. Casual chats with customers allow us to cater for our clients needs. We listen and know what they like. They bring their empty dishes in for us to make them the best lasagne ever (and if its not, we will definitely hear about it). This is what encapsulates the spirit of Ottolenghi: a unique combination of quality and familiarity.

We guess that this is what drew in our first customers. So many of them have become regulars over the years, meaning not only that they come to Ottolenghi frequently but also that we recognise them, know their names and something about their lives. And vice versa. They have a favourite sales assistant who always gets their coffee just right (probably an Italian or an Aussie), their pastry of choice (Lous rhubarb tart), their preferred seat at the table. Our close relationship with our customers extends to all of them, whether its the bustling city stars forever on their way somewhere; the early riser eagerly tapping his watch at five-to-opening; the chilled and chatty sales assistant from next door; the eternal party organiser with a last-minute rushed order; or a parent on the look-out for something healthy to give the children.

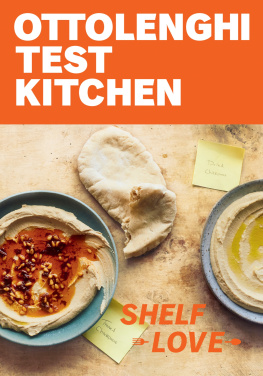

The Ottolenghi cookbook

The Ottolenghi cookbook came into existence through popular demand. So many customers asked for it that we simply had to do it. And we enjoyed every minute of it. We also loved devising recipes for our cooking classes at Leiths School of Food and Wine, some of which appear in this book. The idea of sharing our recipes with fans, as well as with a new audience, is hugely appealing. Revealing our secrets is another way of interacting, of knocking down barriers, of communicating about food.

The recipes we chose for the book are a non-representative collection of old favourites, current hits and a few specials. Some of them have appeared in different guises in The New Vegetarian column in the Guardians Weekend magazine. They all represent different aspects of Ottolenghis food bread, the famous salads, hot dishes from the evening service in Islington, ptisserie, cakes, cold meat and fish and they are all typical Ottolenghi: vibrant, bold and honest.

We have decided not to include dishes incorporating long processes that have been described in detail in other, more specialised books croissants, sourdough bread, stock. We want to stick to what is achievable at home (good croissants rarely are) and what our customers want from the cookbook. We would much rather give a couple of extra salad recipes than spend the same number of pages on chicken stock.

Our histories

Yotam Ottolenghi

My mother clearly remembers my first word, ma, short for marak (soup in Hebrew). Actually I was referring to little industrial soup crotons, tiny yellowish pillows that she used to scatter over the tray of my highchair. I would say ma when I finished them all, and point towards the dry-store cupboard.

As a small child, I loved eating. My dad, always full of expressive Italian terms, used to call me goloso, which means something like greedy glutton, or at least thats what I figured. I was obsessed with certain foods. I adored seafood: prawns, squid, oysters not typical for a young Jewish lad from Jerusalem in the 1970s. A birthday treat would be to go to Sea Dolphin, a restaurant in the Arab part of the city and the only place that served non-kosher sea beasts. Their shrimps with butter and garlic were a building block of my childhood dreams.

Another vivid memory: me aged five, my brother, Yiftach, aged three. We are out on our patio, stark naked, squatting like two monkeys. We are holding pomegranates! Whenever my mom brought us pomegranates from the market, we were stripped and banished outside so we didnt stain the rug or our clothes. Trying to pick the sweet seeds clean, we still always ended up with plenty of the bitter white skin in our mouths, covered head to toe with juice.