Copyright 2012 by Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi

Food photographs copyright 2012 by Jonathan Lovekin

Location photographs copyright 2012 by Adam Hinton

Location photographs copyright 2012 by Nomi Abeliovich

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Originally published in slightly different form in hardcover in Great Britain by Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing, a Random House Group Company, London

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

reproduced by kind permission of The National Library of Israel (Jerusalem); Eran Laor Cartographic Collection

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ottolenghi, Yotam.

Jerusalem : a cookbook / Yotam Ottolenghi, Sami Tamimi.

p. cm.

Includes index.

Includes index.

1. Cooking, Middle Eastern. 2. JerusalemDescription and travel.

I. Tamimi, Sami. II. Title.

TX725.M628O88 2012

641.5676dc23

2012017560

Ebook ISBN9781607743958

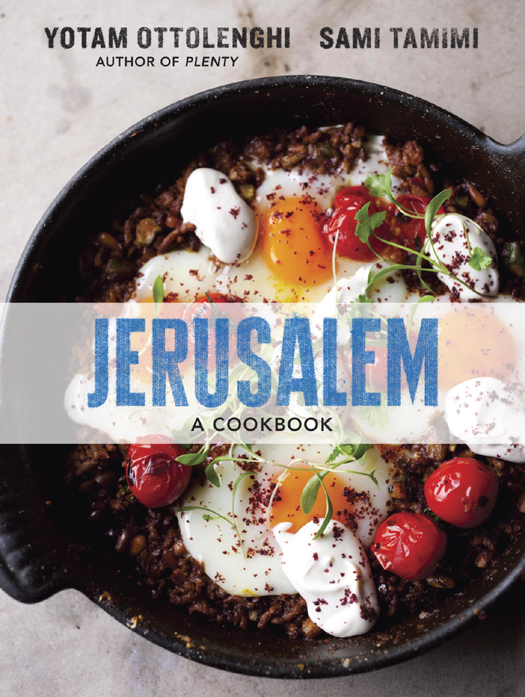

Cover design by Sarah Pulver

Additional prop styling by Sanjana Lovekin

Additional text provided by Noam Bar

Additional text, photography, and research by Nomi Abeliovich

v3.1_r5

Additional text by Nomi Abeliovich and Noam Bar

Food photography by Jonathan Lovekin

Location photography by Adam Hinton

Contents

Introduction

One of our favorite recipes in this collection, ptitim . Both versions were beautifully comforting and delicious.

A dish just like Michaels is part of the Jewish Tripolitan (Libyan) cuisine. It is called shorba and is a result of the Italian influence on Libyan food during the years of Italian rule of the country, in the early twentieth century. So Michaels ptitim was possibly inspired by Tripolitan cooking in Jerusalem, which in turn was influenced by Michaels original Italian culture. The anecdotal icing on this cross-cultural cake is that Michaels great uncle, Aldo Ascoli, was an admiral in the colonial Italian navy that raided Tripoli and occupied Libya in 1911.

Confusing? This is Jerusalem in a nutshell: very personal, private stories immersed in great culinary traditions that often overlap and interact in unpredictable ways, creating food mixes and culinary combinations that belong to specific groups but also belong to everybody else. Many of the citys best-loved foods have just as complicated a pedigree as this one.

This book and this journey into the food of Jerusalem form part of a private odyssey. We both grew up in the city, Sami in the Muslim east and Yotam in the Jewish west, but never knew each other. We lived there as children in the 1970s and 1980s and then left in the 1990s, first to Tel Aviv and then to London. Only there did we meet and discover our parallel histories; we became close friends and then business partners, alongside others in Ottolenghi.

Although we often spoke about Jerusalem, our hometown, we never focused much on the citys food. Recently, howeveris it age?we have begun to reminisce over old food haunts and forgotten treats. Hummuswhich we hardly ever talked about beforehas become an obsession.

It is more than twenty years since we both left the city. This is a serious chunk of time, longer than the years we spent living there. Yet we still think of Jerusalem as our home. Not home in the sense of the place you conduct your daily life or constantly return to. In fact, Jerusalem is our home almost against our wills. It is our home because it defines us, whether we like it or not.

The flavors and smells of this city are our mother tongue. We imagine them and dream in them, even though weve adopted some new, perhaps more sophisticated languages. They define comfort for us, excitement, joy, serene bliss. Everything we taste and everything we cook is filtered through the prism of our childhood experiences: foods our mothers fed us, wild herbs picked on school trips, days spent in markets, the smell of the dry soil on a summers day, goat and sheep roaming the hills, fresh pitas with ground lamb, chopped parsley, chopped liver, black figs, smoky chops, syrupy cakes, crumbly cookies. The list is endlesstoo long to recall and too complex to describe. Most of our food images lie well beyond our consciousness: we just cook and eat, relying on our impulses for what feels right, looks beautiful, and tastes delicious to us.

And this is what we set out to explore in this book. We want to offer our readers a glimpse into a hidden treasure, and at the same time explore our own culinary DNA, unravel the sensations and the alphabet of the city that made us the food creatures we are.

In all honesty, this is also a self-indulgent, nostalgic trip into our pasts. We go back, first and foremost, to experience again those magnificent flavors of our childhood, to satisfy the need most grown-ups have to relive those first food experiences to which nothing holds a candle in later life. We want to eat, cook, and be inspired by the richness of a city with four thousand years of history, that has changed hands endlessly and that now stands as the center of three massive faiths and is occupied by residents of such utter diversity it puts the old tower of Babylon to shame.

IT IS MORE THAN TWENTY YEARS SINCE WE BOTH LEFT THE CITY. THIS IS A SERIOUS CHUNK OF TIME, LONGER THAN THE YEARS WE SPENT LIVING THERE.

Jerusalem food

Is there even such a thing as Jerusalem food, though? Consider this: there are Greek Orthodox monks in this city; Russian Orthodox priests; Hasidic Jews originating from Poland; non-Orthodox Jews from Tunisia, from Libya, from France, or from Britain; there are Sephardic Jews that have been here for generations; there are Palestinian Muslims from the West Bank and many others from the city and well beyond; there are secular Ashkenazic Jews from Romania, Germany, and Lithuania and more recently arrived Sephardim from Morocco, Iraq, Iran, or Turkey; there are Christian Arabs and Armenian Orthodox; there are Yemeni Jews and Ethiopian Jews but there are also Ethiopian Copts; there are Jews from Argentina and others from southern India; there are Russian nuns looking after monasteries and a whole neighborhood of Jews from Bukhara (Uzbekistan).

All of these, and many, many more, create an immense tapestry of cuisines. It is impossible to count the number of cultures and subcultures residing in this city. Jerusalem is an intricate, convoluted mosaic of peoples. It is therefore very tempting to say there isnt such a thing as a local cuisine. And indeed, if you go to the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Meah Shearim and compare the prepared food sold in grocery shops there to the selection laid out by a Palestinian mother for her children in the neighborhood of A-tur in the east of the city, you couldnt be blamed for assuming these two live on two different culinary planets.