For A

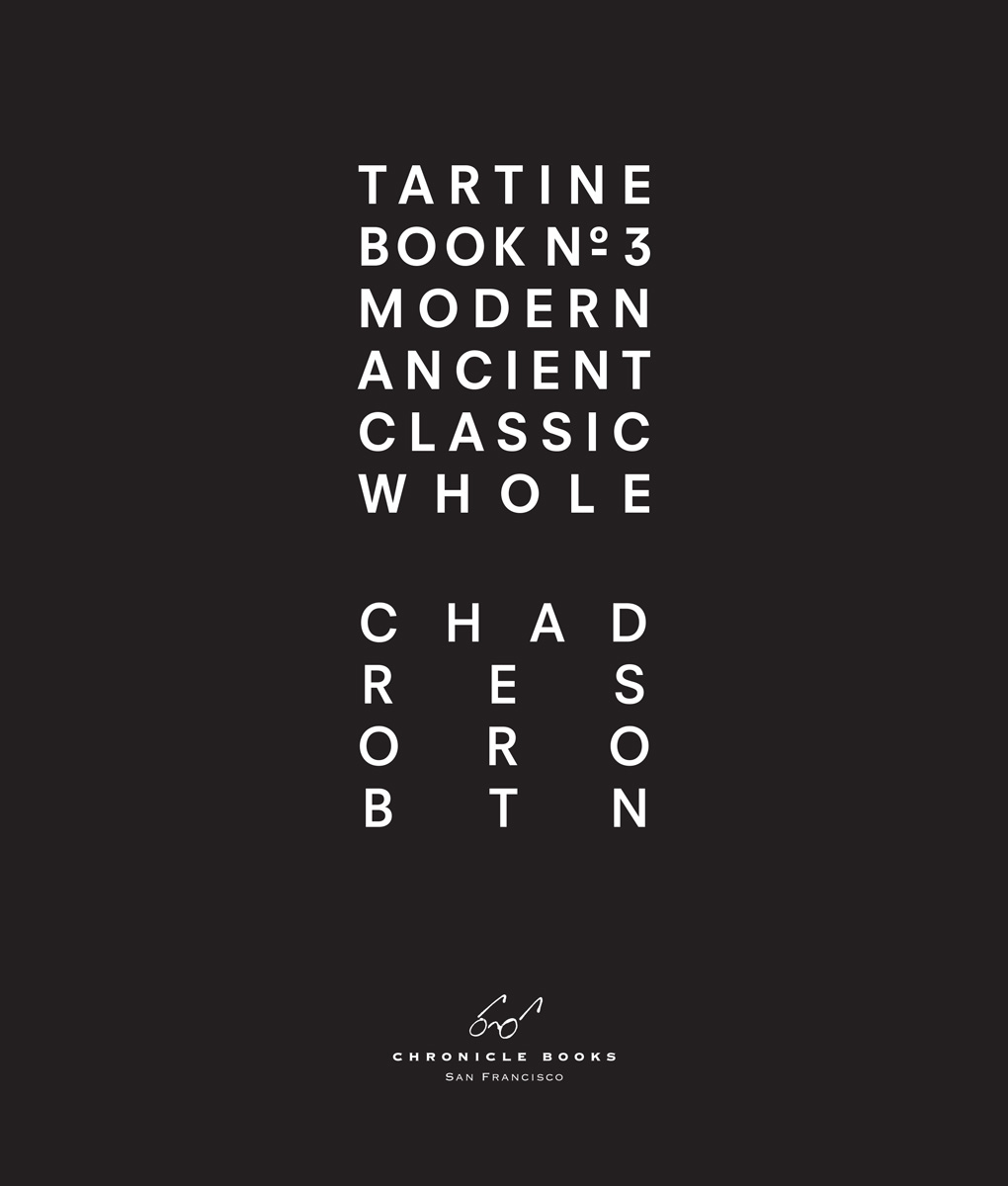

DESIGN

JULIETTE CEZZAR

EDITORIAL DIRECTION

JESSICA BATTILANA

BREAD RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

RICHARD HART

PASTRY RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

LAURIE ELLEN PELLICANO

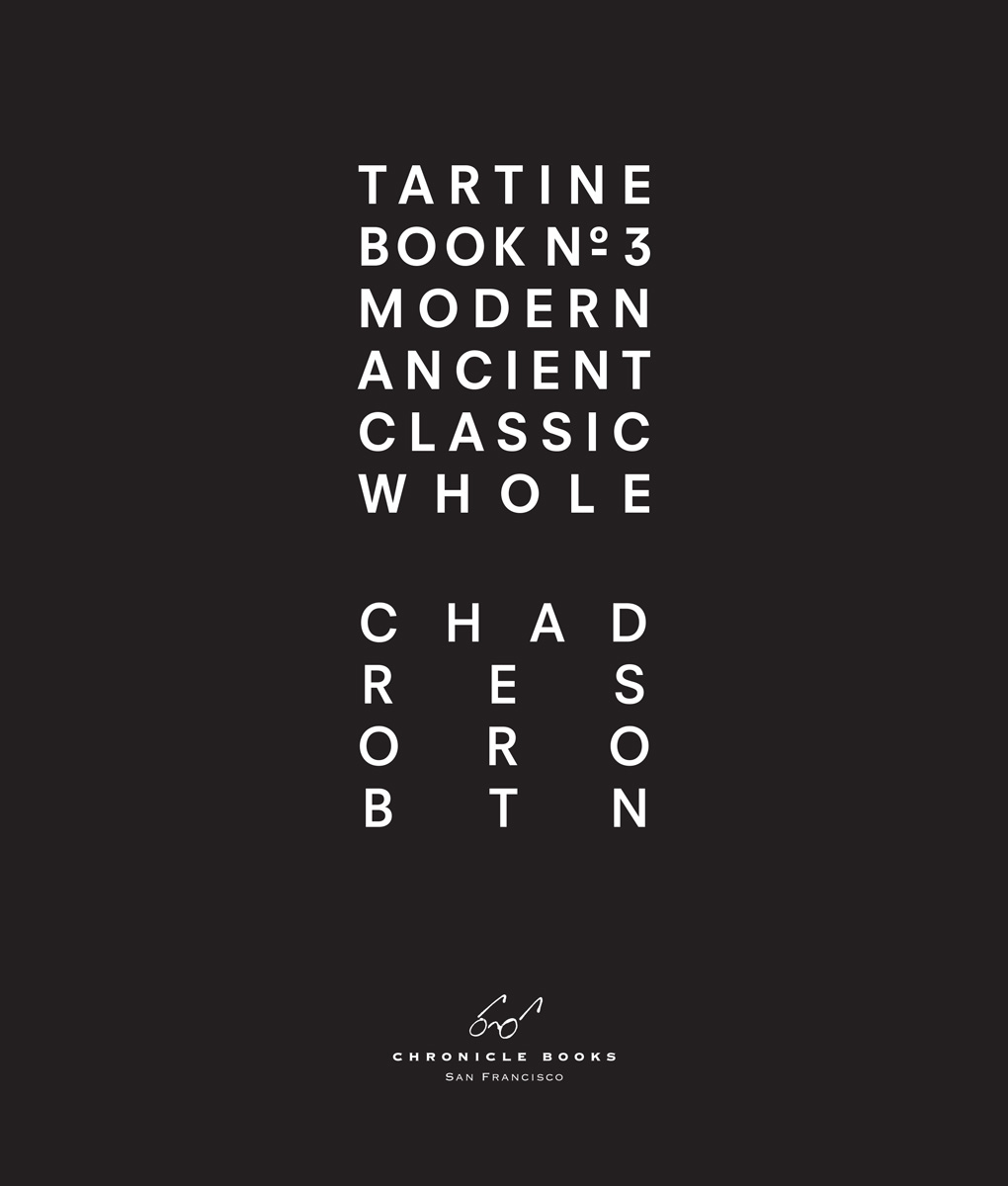

Text copyright 2013 by Chad Robertson.

Photographs copyright 2013 by Chad Robertson.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without written permission from the publisher.

constitute a continuation of the copyright page.

courtesy of Molly Decoudreaux.

courtesy of The Selby.

courtesy of Nadia Erwee.

Photos of Chad in Germany courtesy of Kille Enna.

ISBN 978-1-4521-2846-7

The Library of Congress has previously cataloged this title under ISBN 978-1-4521-1430-9

Valrhona is a registered trademark of Valrhona S.A.

Kamut is a registered trademark of Kamut International, Ltd.

Maldon salt is a registered trademark of Maldon Crystal Salt Company Limited.

Designed by Juliette Cezzar / e.a.d.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

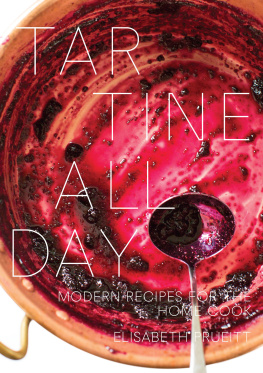

Introduction

Working on the manuscript for my first book, Tartine Bread, was relatively straightforward. Published in late 2010, I told my story of learning to make bread, the people I learned from, and how I adapted techniques to achieve a wide range of results, all while working within a system of self-imposed strictures that were important to me. It was the story of searching for a singular loaf with an old soula traditional natural-leavened bread with all the qualities I loved bound together in one loaf. The basic recipe, which the entire premise of the book was built upon, detailed how to make the basic Tartine country loaf at home. This bread, and all its variations, tilted toward whiter flour and a lighter-flavored loaf.

The manuscript was delivered just as the home-baking movement seemed to reach critical mass. The young leaven method I have become known for, detailed in Tartine Bread, gave many home bakers and chefs the tools they needed to start making their own bread. Ambitious chefs were finally able to gain control over the quality, freshness, and character of the bread they wanted to serve with their food.

In Paris in the late 1970s, Lionel Poilne famously began a dedicated effort to restore the heart and soulle vrai painto the bread of his native France. This marked the beginning of a shift in taste back toward traditional country breads. A generation later, bakers around the world, myself included, were following Poilnes lead. Poilne did not traffic in baguettes; instead he was making a naturally leavened country miche (round loaf) using mostly high-extraction stone-milled wheat flour. Naturally leavened loaves are fermented slowly over a long period, resulting in breads with ancient depths of flavor that have been long forgotten. In doing so, he reintroduced the world to this revelation from the preindustrial French baking tradition.

While France is arguably the birthplace of the most elegant naturally leavened style, these breads are now more widely available than ever. We see natural-leavened bread produced in places where it didnt exist in the same way a decade ago, from London to Copenhagen, Stockholm to Tokyo, Lima to Tel Aviv.

In light of the current trend toward naturally leavened bread, it was clearly time to force a creative push for our team at Tartine not only in our bread, but also with our classic Tartine pastry recipes. The year 2012 marked ten years since opening the bakery. Where could we take our recipes next? Could we make them taste even better while adding more nutrition? Respecting the foundation our reputation had been built on, the need to shift techniques and utilize new ingredients became the driving inspiration and challenge for this book.

For many years I had focused my efforts and exploration on the process of natural fermentation and how far one could push it while still maintaining balanced flavors and ending with an aesthetically pleasing loaf. Initially, I used a few types of flour: some white and some dark whole grains, with differing levels of protein (gluten). From the beginning, I had preferred to make my own flour blends in order to attain the qualities in a final loaf that I was after. Blending your own flours certainly gives more control, allowing the baker to fine-tune the crust and crumb, but much of the nuance in flavor was achieved by using different preferments (prefermented dough) in various stages and adjusting the times, temperatures, and flour percentages in the dough. With a few different types of flours to work with, I chose to focus on the transformative action of the leavens and the vastly different ways natural fermentation could add character to bread.

By the time I started making bread on my own, artisan baking in America was well under way. The Acme Bread Company on the West Coast and others on the East Coast had been making great bread for more than a decade. Our homegrown wheat flour had a reputation abroad as strong flour, well suited for making good bread. It had high-quality gluten that allowed for optimum dough development and fermentation tolerance, resulting in bread with good volume, crust, and crumb (interior texture). But still, for most of us, wheat flours and, for that matter, bread were pretty black and whiteor, rather, brown and white. The general perception of bread fell into two categories: white bread or darker brown whole-wheat bread (with few options in between). The first is made from white flour and the other from all or part wholewheat flour.

Bakers use all sorts of flavorings for breads, such as nuts, seeds, dried fruit, herbs, and cheese. But I have always felt that relying on the addition of nongrain ingredients to add flavor to bread missed the heart of the matter. My focus would rely on the grains to bring the primary flavorherbs, seeds, and other ingredients would complement this foundation.

Having lived in Northern California for the past twenty years, Ive witnessed an incredible increase in the diversity of fruits and vegetables available to us. Years ago, we had a few varieties of tomatoes to choose from, a couple of different kales, and one or two types of broccoli; no one talked much about chicories, brassicas, and alliums, not to mention citrus, stone fruits, herbs, apples, root vegetables, and beans (fresh and dried). Now we have dozens of varieties of each, all with distinct flavors. For cooks this is an inspiring resource. Why, then, have bakers in the States been working with only a few grains for so long?

The answer is not so simple. One must go deep into the history of farming in twentieth-century America, when the goal was to feed a rising population, and examine the shift from diversified farms to monocrop farming, aimed to achieve this goal in what seemed to be the most efficient fashion. As a result, the wheat-growing model was to plant only a few high-yield varieties very intensively. What we lost in this transition were dozens of flavorful varieties that had been grown for generations in careful and sustainable farming practices built on the maintenance of rich soil structures that contributed the most flavor and nutrients to the grain grown in it.

Next page