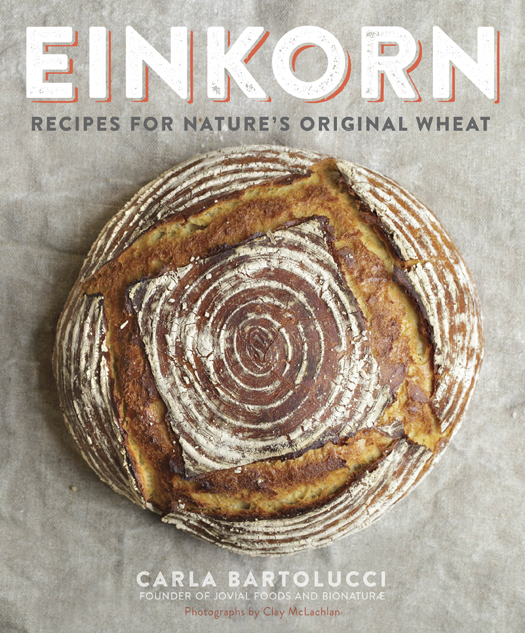

Copyright 2015 by Carla Bartolucci

Photographs 2015 by Clay McLachlan

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartolucci, Carla.

Einkorn / Carla Bartolucci ; photographs by Clay McLachlan. First edition.

pages cm

Includes index.

1. Cooking (Wheat) 2. WheatHeirloom varieties. I. Title.

TX809.W45B37 2015

641.6311dc23

2014040192

ISBN 978-0-8041-8647-6

eBook ISBN 978-0-8041-8648-3

Cover design by Jess Morphew

Cover photographs by Clay McLachlan

v3.1

TO MY GIRLS, GIULIA AND LIVIA

ALWAYS REMEMBER THAT

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF

EACH CHALLENGE IN LIFE

THERE LIES SOMETHING BEAUTIFUL

AND UNEXPECTED

PREFACE

MY PARENTS WERE AMAZING TALENTS IN THE KITCHEN, and both children of Italian-born immigrants. My mother loved people by feeding them, and she never seemed to make a mistake in our little Connecticut kitchen. She understood how flavors came togetherevery dish she served made my childhood a little more special.

My father only cooked on Saturdays, but he was no less skilled than my mother. He would greet his guests with freshly harvested clams and oysters on a bed of ice, accompanied by homemade cocktail sauce, and he dressed his tuna and fennel salad with lemon juice and olive oil. Though a bricklayer, he dreamed of being a fisherman and kept a lobster boat as a hobby. My parents also loved to forage for wild dandelions, which was definitely out of the ordinary in our small coastal town. They made a memorable frittata as well as a fresh dandelion salad, and they prepared skillets of fresh artichokes just as my fathers mother had done in her small fishing village in the Marche region.

Mom and Dad taught us how to love bitter greens and other child-unfriendly vegetables, and their food tasted so fabulous that we never complained or refused. Our steamy little kitchen was the center of our life. For my seventh birthday, I invited my entire class over for my first real party. I know now that my parents worked hard that day, but everything seemed effortless as they brought out trays of pizza to my rowdy little friends. Those kids had never tasted anything like that pizza before and went crazy for it. For the first time, I realized that I could be proud of my Italian heritage.

My own introduction to Italy came at age sixteen. I fell in love with the country at my first meala breakfast on the terrace of crusty bread, homemade marmalade from heirloom apricots, eggs with deep orange yolks, and fresh figs from a huge tree that grew over the balcony. I returned to Italy in 1987 for my junior year abroad at the University of Bologna, where I first met my husband, who was born in nearby Modena. Driving through the countryside on a trip to meet his relatives, he pulled over and plucked a beautifully ripened peach from a roadside orchard for me. It seemed like every inch of Italy was made for farming, and I was captivated by the food unfolding beneath my eyes each season.

We later married and settled in Connecticut, where Rodolfo and I turned our combined love of food, farming, and Italy into a profession. In 1996, we began distributing a brand of Italian-made organic foods, bionatur, in the United States. As our business grew, we felt the need to be closer to where our products were grown and produced, so we returned to Italy to nurture our business. It was a food lovers homecoming, and we were thrilled to discover that our neighbors were not just buying organic foods but also growing them right on their small farms. A neighbor stored his freshly harvested heirloom wheat with bay leaves to deter pests. A short drive to the mountains could get us a whole prosciutto and leaf lard from heritage pigs that foraged on acorns and lived outdoors. We watched our own olives being pressed into fresh extra-virgin oil in the hills above Lago di Garda. The sight of my neighbors sheep roaming free on a breathtaking hill made our enjoyment of his fresh ricotta very special.

I view my life in Italy as a gift that has taught me so much about food and farming.

Yet even as we sought out the best ingredients for our kitchen and the quality of our cooking reached a high point, our oldest daughters health was at a low point. Starting at age two, Giulia had developed intolerances to dairy and eggs. Even after we eliminated those foods from her diet, something continued to cause problems and her symptoms grew more serious. By age seven, she had a constant dry cough and asthma, frequent tonsillitis, and enlarged lymph nodes, and her hair began falling out. It was then that our familys mission to bring einkorn back began.

Years prior to having children, my husband and I had switched to eating mostly ancient types of wheat like spelt. We never suspected wheat as the culprit, but eventually a doctor in Italy told us that Giulias symptoms could be caused by what we now know as gluten sensitivity, a disorder experienced by 18 million Americans, and causes symptoms similar to those of celiac disease.

With this new diagnosis, I realized that we would have to change to a completely gluten-free diet. I had just spent a year carefully developing my own sourdough starter to bake bread at home because I had read that souring flour made gluten more digestible. The bread I was baking was the best my family had ever tasted, and I doubted gluten-free bread could ever be that good. While it was a huge relief to know a healthier chapter in Giulias life was about to begin, there was also sadness about all of the foods she would no longer be able to eat.

Because of our work, my husband and I knew how significantly agriculture had changed over the past century. The era following World War II had changed everything about our food, with the introduction of chemical pesticides and the race to breed new varieties of plants that could grow on a large scale to feed the growing population. We began researching the taxonomy of wheat because we wanted to understand why so many people, including Giulia, were now becoming intolerant to the grain. When we first read about einkorn, the most ancient species of wheat, we got excited and met with the Italian researchers who had been studying it for more than a decade. Einkorn has pure and simple genetics, with fewer chromosomes than other wheat. Einkorn remains more nutritious than modern wheat, containing roughly 30 percent more protein and more antioxidants, B vitamins, and essential dietary and trace minerals. In genetic testing, einkorn was found to lack certain gluten proteins that people with wheat intolerances cannot digest.