Contents

Bilingual Deaf and Hearing Families

Bilingual Deaf and Hearing Families

NARRATIVE INTERVIEWS

Barbara Bodner-Johnson

Beth Sonnenstrahl Benedict

Gallaudet University Press WASHINGTON, DC

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2012 by Gallaudet University

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America

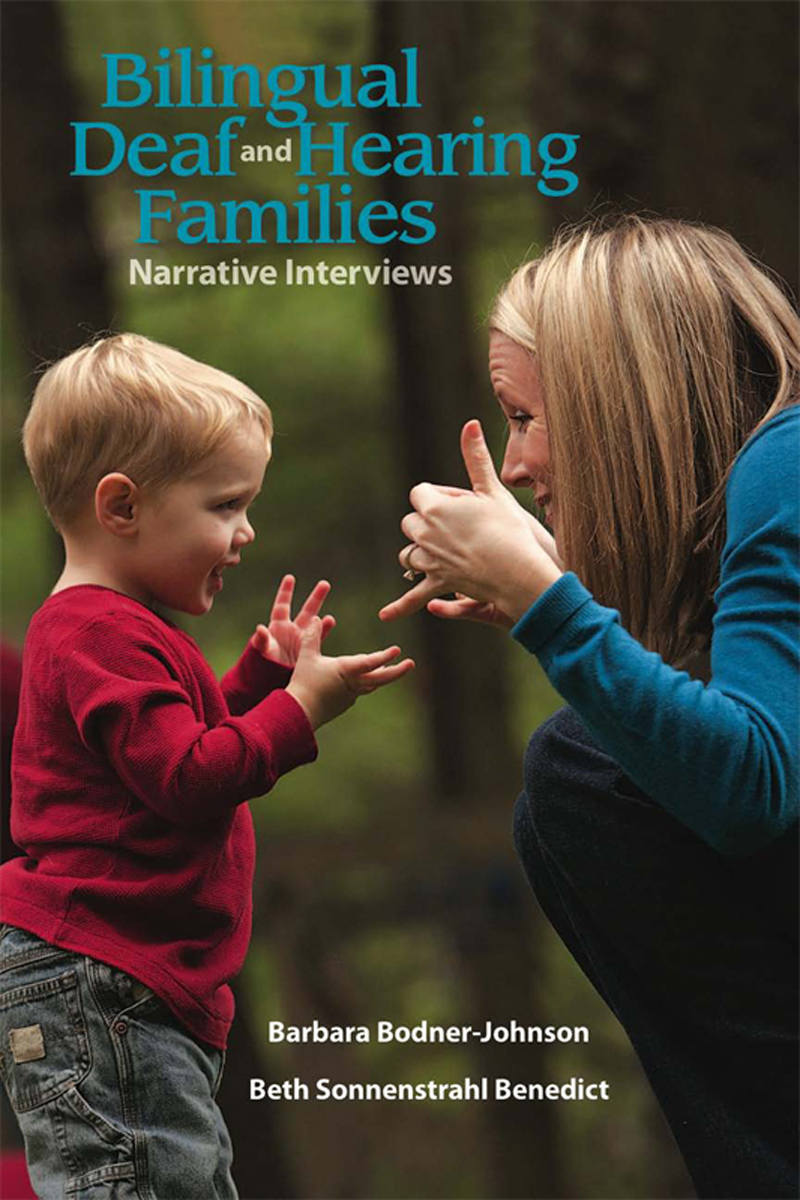

All photographs that appear in this book were taken by and appear courtesy of Barbara Bodner-Johnson.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bodner-Johnson, Barbara.

Bilingual deaf and hearing families: narrative interviews / Barbara Bodner-Johnson, Beth Sonnenstrahl Benedict.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-56368-529-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 1-56368-529-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-56368-530-9 (e-book) ISBN 1-56368-530-2 (e-book)

1. DeafMeans of communicationCase studies. 2. Hearing impairedMeans of communicationCase studies. 3. Communication in familiesCase studies.

I. Benedict, Beth Sonnenstrahl. II. Title.

HV2471.B63 2012

305.90820922dc23

2012017445

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

W E HUMANS can contribute to history in many ways. The way we live our livesour dilemmas, decisions, and choicescontributes to our personal history. Our interactions with our families, neighbors, community, and colleagues at work contribute to a larger social and cultural history. And every now and then, we contribute to the making of history. The present authors, Barbara Bodner-Johnson and Beth Sonnenstrahl Benedict, indeed contribute to the making of history, and this pioneering book, Bilingual Deaf and Hearing Families , couldnt have come at a more perfect time.

We presently stand at a great crossroad in societys understanding of the needs of a healthy growing mind, especially involving the needs of the young deaf childs healthy growing mind. Like the titration chemistry experiments from our high school days, whereupon one final squeeze of the dropper radically changes the liquid from clear to technicolor, we teeter on a similar moment of radical conceptual change in society, one that provides a richer, more vibrant vision into the educational and developmental needs of young deaf children.

In the pages within, Bodner-Johnson and Benedict offer the reader a vastly rich view into the developmental and educational needs of young deaf children. They provide the pivotal, previously missing dropsthe key pieces of evidenceto lead society from its first flash of insight to fundamental conceptual change. The key pieces of evidence they present are twofold. First, from their theoretical understanding of the interdependence of the individual and the individuals society, the authors lay bare a crucial factor that contributes to a young childs healthy linguistic, cognitive, and social-emotional growth. Specifically, they provide a new lens on the impact of the family in a developing childs life. Through personal discussion with ten families, and described through the families own words, the authors respectfully reveal the ways that families with deaf children live their daily lives. The knowledge advanced from this vantage point alone will help all families, particularly families with deaf children, and the book does more. To be sure, this book enriches the knowledge that professionals can bring to their practices.

Yet there is a second history-making vantage point offered in this book. It involves the authors important focus on bilingualism, and the remarkable advantages that bilingual education affords to all developing children. With astute knowledge, and through impressive scholarship, the book reveals the stunning cognitive, linguistic, and social-emotional advantages when deaf children grow up with both a signed language and a spoken languagehere, American Sign Language (ASL) and English. Powerfully, the families accounts comprise a vivid technicolor of unique evidenceevidence that is rendered especially poignant through the use of these living examples that show the benefits of early bilingual ASL-English language exposure.

And herein lies the richest historical impact of this book. The crossroad that I mention above is not just a metaphor for the choices that we make of an abstract, philosophical nature. Goodness, the issues here couldnt be farther away from medieval philosophical contemplations about, for example, the number of angels that can dance on the head of a pin! Instead, the kind of choices that families with deaf children now face can be life-altering for the deaf child, her family, and, ultimately, for society. The stakes parents face about which road to take in raising a deaf child are now the highest that they have been in history.

On the one hand, modern technological advances in auditorytransmission devices (e.g., cochlear implants) as well as improved surgical procedures have led some professionals to direct parents toward one exclusive path to follow when educating their young deaf child. Here, some parents are urged to maintain strict adherence to a speech-only educational strategy, and any concomitant exposure to a natural signed language, like ASL, is viewed as damaging the childs ability to learn English and English literacy skills.

On the other hand, stunning advances in the capacity to neuroimage the developing infants brain while acquiring one language as compared to acquiring two languages (be they two spoken languages or a spoken and a signed language)coupled with advances in behavioral methods to test what infants knowhave led to two revolutionary advancements. First, we understand the benefits of early sign language exposure for the young deaf child. Second, we understand the benefits of bilingual language exposure in early life.

Here, old myths about the detrimental impact of early exposure to signed language are now crashing down. Early language exposure to a signed language, and especially early bilingual exposure to ASL and English, afford striking advantages in language, reading, and cognitive processing that actually facilitate reading and literacy skills in English. Moreover, old fears of losing a young deaf child if he or she is exposed too early in life to a signed language, and language delay by exposing a child to two languages early in life, are now widely understood to be scientifically unfounded.

Early Signed Language Exposure : The brain and behavioral studies from my science laboratory spanning three decadesas well as discoveries from the science laboratories of many other researchershave consistently revealed that early exposure to a natural signed language is highly beneficial to normal human language and cognitive development. Remarkably, early exposure to a signed language in young deaf infants changes their brains visual attention processing. This, in turn, has positive upstream impact on their higher cognitive and language learning abilities, as well as on their enhanced capacity for social-emotional self-regulation. As deaf infants grow into toddlers, studies of these children during book reading with their signing parents have found heightened eye gaze tracking ability relative to children without sign input, which, in turn, is vital to early vocabulary, language, reading, and literacy mastery, both in ASL as well as in English. Thus, an important consequence of exposing young deaf children to a natural signed language early in life is that it affords an advantaged visual capacity, which, in turn, facilitates the childs ability to achieve healthy and developmentally appropriate cognitive, language, and reading milestones.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.