CONTENTS

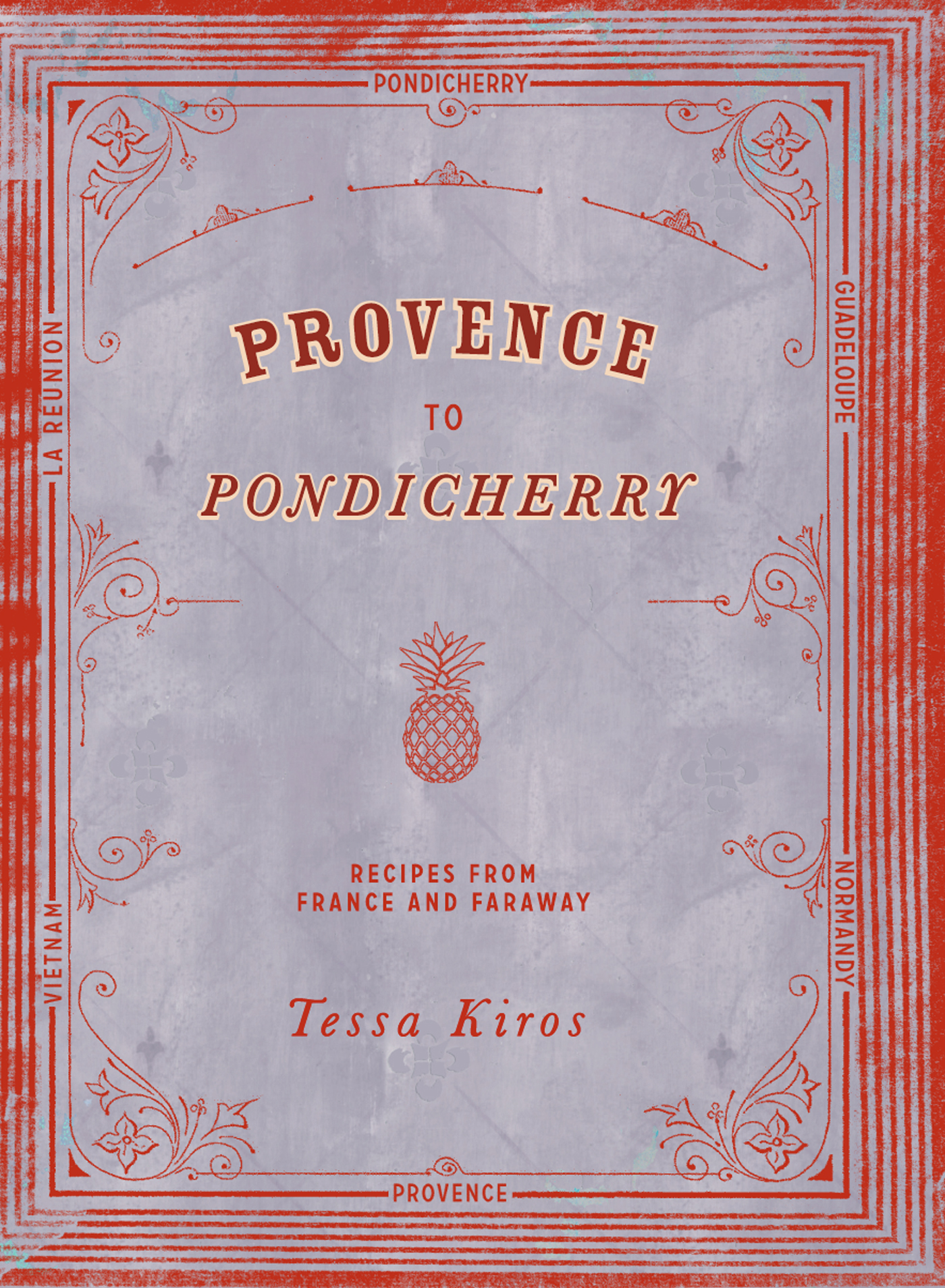

On a journey to Paris, I watched a family travelling with a beautiful collection of baskets. The mother was dark and freckled. I wondered where they were from, and so I asked them: The baskets Laos. And the family she was born in Martinique, to a father from Guadeloupe and a Parisian mother, and grew up in Paris, where she met her husband pure French. And here they were bringing home baskets and other treasures from around the world.

Paris and other parts of France are now such an assemblage a fascinating mix. The airport in Paris is a bustling commotion. Around me there are women with madras cotton cloths on their heads and knotted foulards, travelling to their homeland for the summer. Entire extended families upping and downing, from the mtropole that they now call home to other dpartements scattered around the world. Some are carrying breadfruits back from Guadeloupe, palm hearts from La Runion, and green mangoes and other parcels of speciality. It is incredible to see a tapestry so richly intertwined from so many traditions and cultures around the world. Stitched together with French threads.

In the 1600s France began forming trading companies, establishing overseas colonies to compete with Spain, Portugal, the United Provinces (Holland) and Britain. Other than financial gain and imperial prestige, spreading Catholicism as well as the French language and culture were among the objectives. Trade routes to the Far East and the Americas were established, and new and exotic foods were brought back to Europe by the shipload.

Potatoes, tomatoes, fresh peppers and maize were among the first and exciting discoveries from the New World. Spices such as cloves, nutmeg and pepper had been arriving overland from the East for awhile, and were already customary in European cuisine. But it was the challenge to find more economical routes to the spice trade of the East that motivated the great seafarers.

Not all trade was in unusual ingredients. The new territories also provided land to cultivate products like tobacco, wheat and sugar, which were in increasing demand in Europe. As settlements flourished, produce from Europe travelled to the colonies and a market for European goods grew. Immigrants brought back familiar foods with them and introduced their own flavours, and so began the weaving of one cuisine into another a blending of spices, methods and tastes that quietly settled into the culture at each end of the voyage.

Later, with the breaking up of France's colonial Empire, several of the colonies were lost to war or independence. Others were incorporated into France as overseas departments these dpartements and territoires doutre-mer remaining today as part of the French Union.

My own journey began in Provence, with my appreciation of the fabrics, colours and patterns. I thought about my first trip to India and the details and designs of the cottons there. How one inspires and connects to another. How a loaf of bread in France can become an everyday essential in a country half a world away. I had been dreaming of the sun of Provence and the mist of Normandy, located respectively on the shores of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean. These two places, among others, provided continental France with access to travel the world. I had listened to stories about fascinating faraway places, where French governors had been deposited and where fragrant fruits and wonderful people mingled with the scents of cinnamon and ginger.

I wanted to go to some of these places where French explorers had established colonies. Dragging hessian sacks and wooden tea crates filled with fine porcelain across oceans, to settle their families and display their wares far off in tropical temperatures under whirring ceiling fans in vanilla and rum ambiences. I wanted to discover the foods and flavours and how these had been mixed with different traditions and new lands.

Traces of the French zest for adventure are today sprinkled across the world map. The places I am instinctively drawn to, with their lyrical names and evocative images, are all reached by water. An obvious consequence of the seafaring nature of colonialism, this has also given these places a cuisine laden with ingredients from the sea. It is lovely to see how iridescent fish, mussels and crayfish can be common to all these places but arrive at the table as ambassadors to their nation. Flambed in rum, simmered in tomatoes and spices, steeped in saffron or a splash of coconut cream the result is a dish true to its homeland, and yet undeniably tied to another nation.

This is a collection of recipes from my travels to some of these places.

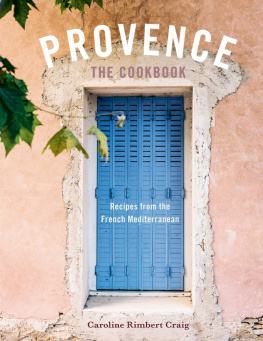

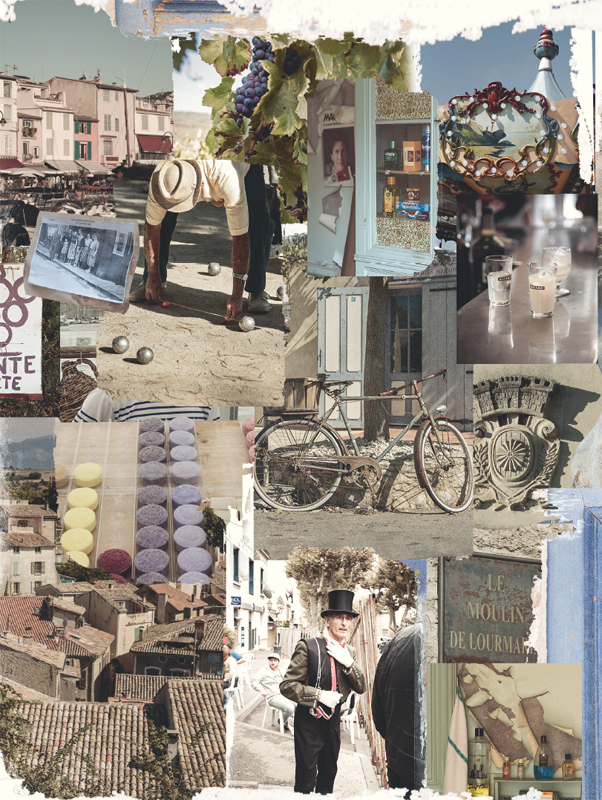

PROVENCE

HERE IS WHERE MY JOURNEY BEGAN,

THE PLACE THAT DREW MY THOUGHTS OF LONG SEA VOYAGES

AND TRADING WITH FOREIGN LANDS TOGETHER.

I am lucky that I live near enough to Provence to be able to drive there on a whim for an almond croissant, or bouillabaisse. And come home then, with baskets of treasures, resources and tales of aoli.

Provincia Romana the first Roman province outside Italy became Provence. It has been a part of France since 1481, but still retains its own very strong cultural identity and dialect, particularly noticeable in the smaller villages. Its capital Marseille, a main town and port, was, along with Toulon, a major gateway for the French empire to North Africa and the Orient, for the exchange of exotic spices and produce.

There are lemons and oranges in Menton, the first town I arrive in. I stop in Nice for socca from the market in the old town. Its well worth the traffic: they are crisp, paper-thin and well seasoned. The cook scuffs off pieces from her huge pan and settles them into a paper cone for me, scattering enough finely ground pepper over to make the chest burn. Eat it here and now, she says to me a couple of times. She even breaks off from serving her next customer to tell me again, that I must eat it while it is still warm.