Table of Contents

FRENCH PROVINCIAL COOKING

Elizabeth David discovered her taste for good food and wine when she lived with a French family while studying history and literature at the Sorbonne. A few years after her return to England she made up her mind to learn to cook so that she could reproduce for herself and her friends some of the food that she had come to appreciate in France. Subsequently, Mrs David lived and kept house in France, Italy, Greece, Egypt and India, as well as in England. She found not only the practical side but also the literature of cookery of absorbing interest and studied it throughout her life.

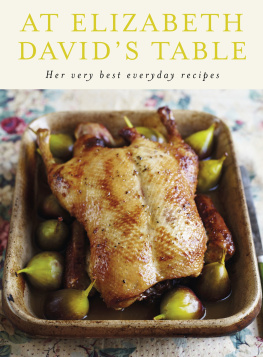

Her first book, Mediterranean Food, appeared in 1950. French Country Cooking followed in 1951, Italian Food, after a year of research in Italy, in 1954, Summer Cooking in 1955 and French Provincial Cooking in 1960. These books and a stream of often provocative articles in magazines and newspapers changed the outlook of English cooks forever.

In her later works she explored the traditions of English cooking (Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen, 1970) and with English Bread and Yeast Cookery (1977) became the champion of a long overdue movement for good bread. An Omelette and a Glass of Wine (1984) is a selection of articles first written for the Spectator, Vogue, Nova and a range of other journals. The posthumously published Harvest of the Cold Months (1994) is a fascinating historical account of aspects of food preservation, the world-wide ice-trade and the early days of refrigeration. South Wind Through the Kitchen, an anthology of recipes and articles from Mrs Davids nine books, selected by her family and friends and by the chefs and writers she inspired, was published in 1997, and acts as a reminder of what made Elizabeth David one of the most influential and loved of English food writers.

In 1973 her contribution to the gastronomic arts was recognized with the award of the first Andr Simon memorial prize. An OBE followed in 1976, and in 1977 she was made a Chevalier de lOrdre du Mrite Agricole. English Bread and Yeast Cookery won Elizabeth David the 1977 Glenfiddich Writer of the Year award. The universities of Essex and Bristol conferred honorary doctorates on her in 1979 and 1988 respectively. In 1982 she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and in 1986 was awarded a CBE. Elizabeth David died in 1992.

To

P. H.

with love

Acknowledgements

So many people have helped me in so many ways with the compiling and the production of this booksome with advice and material, others with technical assistance, typing, indexing, proof-readingthat the acknowledgements which I should like to make to all these friends would fill a number of pages.

But I have only a limited space, so I must restrict myself, first of all, to thanking Miss Audrey Withers, for so many years editor of Vogue, for making it possible for me to go to France on several journeys to collect material for cookery articles subsequently published in the magazine. It is these articles, with a number published in House and Garden between 1956 and 1959, which form the nucleus of this book.

Other material and recipes republished here first appeared in The Sunday Times, Harpers Bazaar, The Wine and Food Society Quarterly, Harrods Food News and Wine, edited by T. A. Layton.

M. Andr Simon very kindly gave me permission to reprint an article by Mrs. Belloc Lowndes which first appeared in The Wine and Food Society Quarterly, and Messrs. A. D. Peters to include an extract from Marcel Boulestins Myself, My Two Countries, published by Cassell & Co. Messrs. Martin Secker & Warburg have also kindly allowed me to reprint a passage from Maurice Goudekets Close to Colette, and Mr. Vivian Rowe has generously permitted me to reproduce an excerpt from Return to Normandy, published by Messrs. Evans Brothers.

Lastly, it would be ungrateful of me to miss this opportunity of thanking my friend Doreen Thornton for driving me, with much patience and care, on many rather arduous journeys around and across France in search of good food and interesting regional recipes.

Introduction

STAYING in Toulouse a few years ago, I bought a little cookery book on a stall in the march aux puces held every Sunday morning in the Cathedral Square. It was a tattered little volume, and its cover, attracted me. In faded pinks and blues, it depicts an enormously fat and contented-looking cook in white muslin cap, spotted blouse and blue apron, smiling smugly to herself as she scatters herbs on a gigot of mutton. Beside her are a great loaf of butter, a head of garlic and a wooden salt box, and in the foreground is a table laid with a white cloth and four places, a basket of bread, a cruet and two carafes of wine.

The promise of the cover was, indeed, fulfilled in the pages of this delightful little book, called Secrets de la Bonne Table, 120 Recettes indites recueillies dans les provinces de France. The author, Benjamin Renaudet (date of publication not disclosed, but probably about 1900), had collected genuine recipes from country housewives, gourmet doctors, lawyers and senators, from gamekeepers and their wives, from landladies of seaside pensions, from the notebooks of family and friends. The dishes described are not spectacular, rich or highly flavoured, the materials are the modest ingredients you would expect to find in a country garden, a small farm, or in the market of a quiet provincial town. But it is not rustic or peasant cooking, for the directions for the blending of different vegetables in a soup, the quantity of wine in a stew, or the seasoning of the sauce for a chicken reflect great care and regard for the harmony of the finished dish. This is sober, well-balanced, middle-class French cookery, carried out with care and skill, with due regard to the quality of the materials, but without extravagance or pretension.

The book exudes an atmosphere of provincial life which appears orderly and calm whatever ferocious dramas may be seething below the surface. Here you find the lawyers wife at work preparing her special noisettes dagneau for a dinner party; a great-aunt of one of the authors friends serves the same soup her mother served to Madame Rcamier when she came to dinner; the farmers wife gathers mushrooms to garnish the chicken she is cooking for her husband when he comes in with friends from a days shooting; a senators cook proves to a sceptical company that an old hen can be made into a dish fit for a gourmet; the authors great-uncle at last discloses his recipe for the liqueur he makes every year and keeps locked in his linen-cupboard.

The ravages of two world wars, the astronomical rises in the cost of living, and the great changes brought about by modern methods of transport and food preservation have not destroyed those traditions of French provincial cookery. In one way indeed these circumstances have oddly combined to preserve them. After the 1914 war patriotic Frenchmen began to feel that the unprecedented influx of foreign tourists hurrying through the country in fast cars, Riviera or Biarritz bound, not caring what they ate or drank so long as they were not delayed on their way, was threatening the character of their cookery far more than had the shortages and privations of war. Soon, they felt, the old inns and country restaurants would disappear and there would be only modern hotels serving mass-produced, impersonal food which could be put before the customers at a moments notice, devoured, paid for, and instantly forgotten. It was at this time that a number of gourmets and gastronomically-minded men of letters set about collecting and publicising the local recipes of each province in France.