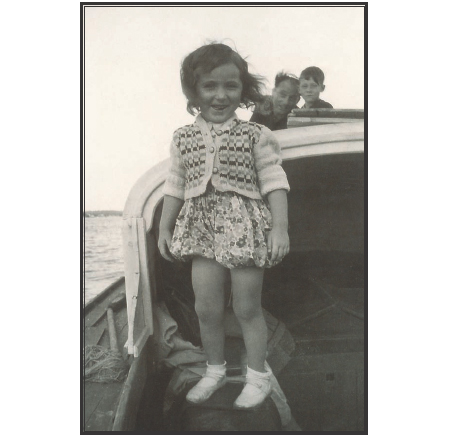

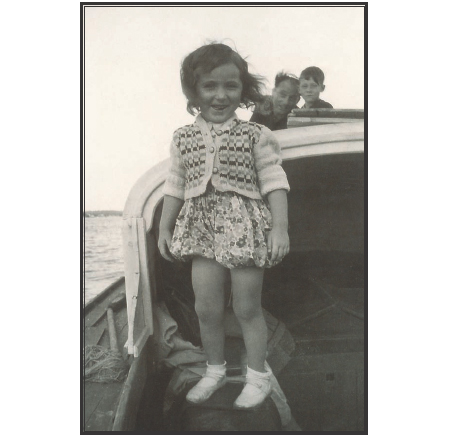

DANY AT 4 YEARS OLD, THE BASSIN DARCACHON, 1946

MY MOTHERS SISTER, MARIE-ANTOINETTE, AND I WERE SITTING ALL ALONE IN THE ENORMOUS DINING ROOM AT THE SPA AT LUZ-SAINT-SAUVEUR IN THE PYRENEES, AN HOUR BEFORE THE OTHER CURISTES (SPA CLIENTS) CAME IN FOR THEIR LUNCH. AT MY AUNTS REQUEST, THE CHEF HAD PREPARED SOMETHING JUST FOR ME A DELICATE DISH OF PAN-FRIED TROUT WHICH HAD BEEN CAUGHT IN A NEARBY MOUNTAIN STREAM. TATIE ANTOINETTE WAS GENTLE AND PATIENT, AND SAT NEXT TO ME, URGING ME TO EAT IN HER OWN, SWEET WAY: MANGE, DANY. MANGE, DANY.

I WAS FOUR YEARS OLD AND SERIOUSLY UNDERWEIGHT; a little stick figure with hollow cheeks and matchsticks for limbs. Id been refusing food for almost a year and nothing my parents did could persuade me to eat. They were at their wits, end, so when my aunt offered to take me along on her annual visit to the spa to try and fatten me up a bit they quickly agreed.

At home, my parents were always arguing. Although my father, Max, was a generous, good-hearted man, he lacked an education and had never learned to control his temper. My mother Madeleine knew just how to tease him and often provoked him into a full-blown rage. Sadly, this often happened just as the family sat down to eat: insults and shouts would be hurled across the table, followed by plates and saucers that shattered bang, boom, crash into one hundred pieces against the wall and the floor. When they werent arguing, I hardly saw my parents. My Papa was always preoccupied with work and my Maman had neither the time nor the inclination for cuddles or caresses, reading stories or playing games. She would give me a few toys and then disappear. I had a brother, Michel, who was seven years older, but we had little in common and rarely spent time together. The only way I thought I could get any love and attention in my family was to starve myself.

There was, however, one thing I couldnt resist and that was the love and attention lavished on me by my kind, sweet Tatie Antoinette, who sat so patiently with me in the spa dining room that day, imploring me to eat. Mange, Dany. Mange, Dany. Finally, I gave in to her gentle pleas and ate properly for the first time in a very long time.

After finishing my meal, Tatie Antoinette took me back to our room for a sieste and went to enjoy her own lunch with the other curistes. The minute she was gone I leapt out of bed and bounced around the room, waiting, impatiently, for her to return. Although she was only away for about an hour, it seemed, at the time, to be an eternity; after lunch Tatie went and lay down on a chaise longue under a shady tree on a beautiful green lawn that sloped down to a stream. I know this because by standing on my tiptoes on a stool in the bathroom I could look down and spy on her. Along with the sound of her sweet voice coaxing me to eat, I can still recall that image of Tatie Antoinette relaxing in the dappled shade of the garden, listening to the gurgling stream and breathing in the fresh mountain air. She was, like the other guests, relieved that the war was finally over, that peace had come at last and that her funny little niece had decided to break her year-long fast.

Refusing to eat had been the perfect weapon to use against a family devoted to food. We lived in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, a bustling market town on the Dordogne River just east of Bordeaux, on the border of the dpartements of the Gironde and Prigord. My father was the youngest of five sons, and had taken on his fathers business as a ngociant en bestiaux (a dealer in livestock). He rose at three oclock most mornings to don the traditional dark-blue smock and overalls of a merchant, which protected his shirt and trousers from the filth. He would then lurch off in his rickety, old cattle truck to les forails, the livestock markets in the Limousin, Tulle, Brive and Cahors; sometimes he even went as far south as the Pyrenees. If Papas truck didnt break down, he would return in time to sell the animals to local butchers in Ste-Foys march, a beautiful covered market located at the end of our street, on the edge of town.

My fathers mother, Grandmre Alice, was famous for her cooking in Ste-Foy. In the late 1920s she ran her own charcuterie shop in the village, where she made sausages, pts, and meaty rillettes. It was there that she gave Maman her first lessons in commercial-scale cooking. Grandmre Alices apricot tarts made from brioche dough were legendary and so large they couldnt fit into a conventional oven. Instead, she had to take them to the local boulangerie, where it was commonplace for customers to put dishes in the still-piping-hot ovens after the days bread had been baked.

Another of her specialities was boudin (black pudding), some of which inevitably exploded while being poached. Grandmre would add vegetables to the boudin stock to make a delicious soup called jimboura that is unique to this pocket of France. Still, to this day, there is a charcutier in the Ste-Foy market that makes this dish in the winter months; whenever the blackboard sign outside the shop advertises