All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

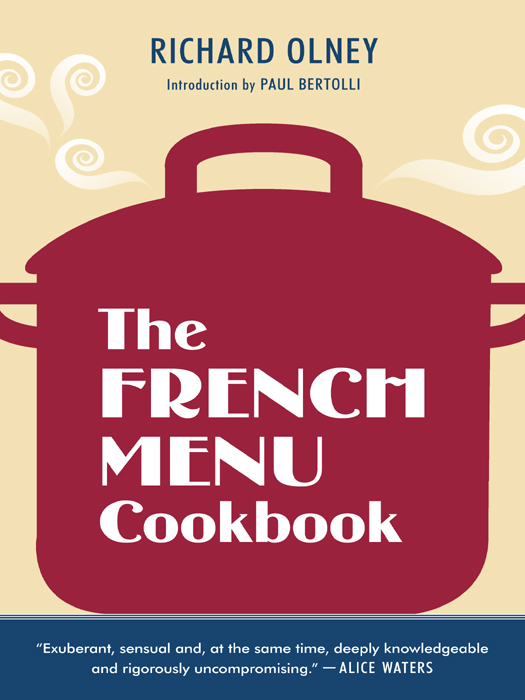

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Simon and Schuster, New York, in 1970. Subsequently published in hardcover with a new introduction by Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, in 2002.

INTRODUCTION

TO THE NEW EDITION

Every aspiring chef needs at least one mentor. Richard Olney was mine. Before I had the pleasure of meeting him in person, I knew him through his early books, The French Menu Cookbook (1970) and Simple French Food (1974), both of which influenced me more profoundly than any culinary writing of the time and any I have since encountered. These books occupy my culinary consciousness. Their spirit lives in the spirit of what I do.

It was altogether fortunate that the first publication of The French Menu Cookbook coincided with my awakening as a cook. Without it I would be much less of a cook now, perhaps no cook at all. Some ten years later, my interest in this book became intense. At the time, as the new chef of Chez Panisse restaurant, I had the responsibility of creating the nightly changing prix fixe menu, and The French Menu Cookbook seemed personally addressed to me. Olney, a friend to Chez Panisse and guest author of several of its special menus devoted to French wine and food, also instructed me by handwritten notes sent from abroad on a few occasions. It was my honor to cook for Richard several times, and his generous estimations of the menus I prepared freshened my confidence and bolstered my pride. I cannot say I knew him well, and in this respect my relationship with his words and his thinking was, and still is, pure. I like it that way. In my five or six encounters with Richard both here and in France during the later years of his life, I found him to be a man of few words, a surprising revelation given how large his writing loomed in my imagination. It was from others that I learned of his charmed life on the herb-scented Provenal hillside he called his home. Olney had frequent visitors who would often stay for days, sometimes weeks, in thrall to his cooking and the seductions of his cellar. His appearance was as unabashed as his cooking. I am told he received summer guests wearing no more than a loincloth. To those who kept his close company, Olney was a curious blend of cultured gentleman and lusty sybarite, a disciplined intellectual with the appetites of a beast. He did not suffer fools or foolishness. He was often irascible. On topics of food and wine he was a brilliant reductionist, caustically opinionated, infuriatingly right. Despite his steady habit of Gauloise cigarettes and a dizzying capacity for wine and spirits, he possessed an acutely discerning palate. This quality was ever-present during our shared moments at the table and is everywhere evidenced in The French Menu Cookbook and in all of his books that followed.

It is a testament to the enduring quality of a book that one can revisit it after thirty years and find it to be in every way as revealing and vital as it was upon first opening it, if not more so. Influence is something that can only be understood fully in retrospect. Re-reading The French Menu Cookbook reminds me of what I was looking for some thirty years ago when I was struggling to find my way as a chef, and what it was that I found in Richard Olneys words. In some important respects, we shared similar sensibilities, perhaps even a parallel path to discovering our passion for food and wine. I had moved away from the pursuit of a career in another art form, music, while Olney had started out as a painter. The transition was not easy for me. While the world of food and wine proved far more accessible and rewarding to my efforts, I missed the quiet intensity, the emotional gratification, and the enduring reward of music making. Before my introduction to The French Menu Cookbook I had worked in a number of local restaurants and had spent a grueling year of restaurant apprenticeship abroad. I knew even after I had landed a more comfortable job at Chez Panisse that I would have to find some higher purpose if I were to sustain the profession and the life. Restaurant cooking was fast, loud, hot, late, dirty, imprecise, exhausting, and joyful. What satisfaction could be had from a days preparation was sadly fleeting. In my worst moments, I viewed the fruit of my hard work, so many beautifully styled plates, reduced to sewage in a matter of hours.

I floundered for nearly a decade trying to find the metaphor in cooking that would reconcile my passion for the elegance of music with the rough kitchen work that was pulling me strongly. The French Menu Cookbook was the poem that released me from turmoil. It embodied the purpose I sought and was critical in helping me legitimize my choice to become a chef. In it, I found an artists eye for the telling detail and for the beauty of food, and a craftsmans patience with process. Olneys menus for all seasons and moods were luminous examples of the possibilities for achieving economy and harmony of form. Olney was a classicist, yet he maintained a relaxed relationship with tradition. Aware of the folly of prescriptions for wine etiquette, menu planning, and food pairing, he warned that one must not take all of this too seriously it is great fun to make up rules and then disprove them, or attempt to. Beyond his carefully reasoned approach, and the trouble he took to conceive and prepare a meal, was a clear sight of the goal: Food was to be celebrated, raucously enjoyed.

As a writer, Olney forged a melodious, often delicious language that is intimately matched to the sensual language of cooking. His natural powers of description stemmed, I believe, from his own highly developed tactile sense, what he considered to be

a sort of convergence of all the sensesthe awareness through touching, and also through smelling, hearing, seeing, and tasting that something is just rightto know by seeing the progression from the light, swelling foam of an initial boil to a flat surface punctuated by tiny bubbles, by hearing the same progression from a soft, cottony, slurring sound to a series of sharp, staccato explosions, by judging from the degree of syrupiness or the smooth, enveloping consistency on a wooden spoon when a reduction has arrived at the point, a few seconds before which it is too thin, a few seconds after which it will collapse into grease or burn; to know by pinching and judging the resilience of a lamb chop or a roast leg of lamb when to remove it from the heat; to recognize the perfect amber of a caramel the second before it turns burnt and bitter; to feel the right fresh-heavy-cream consistency of a crpe batter and the point of light but consistent airiness in a mousseline forcemeat that, having absorbed a maximum of cream to be perfect, would risk collapsing through any further addition.