THE SOCIAL ORIGINS OF LANGUAGE

THE SOCIAL ORIGINS OF LANGUAGE

ROBERT M. SEYFARTH

AND

DOROTHY L. CHENEY

Edited and Introduced by Michael L. Platt

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

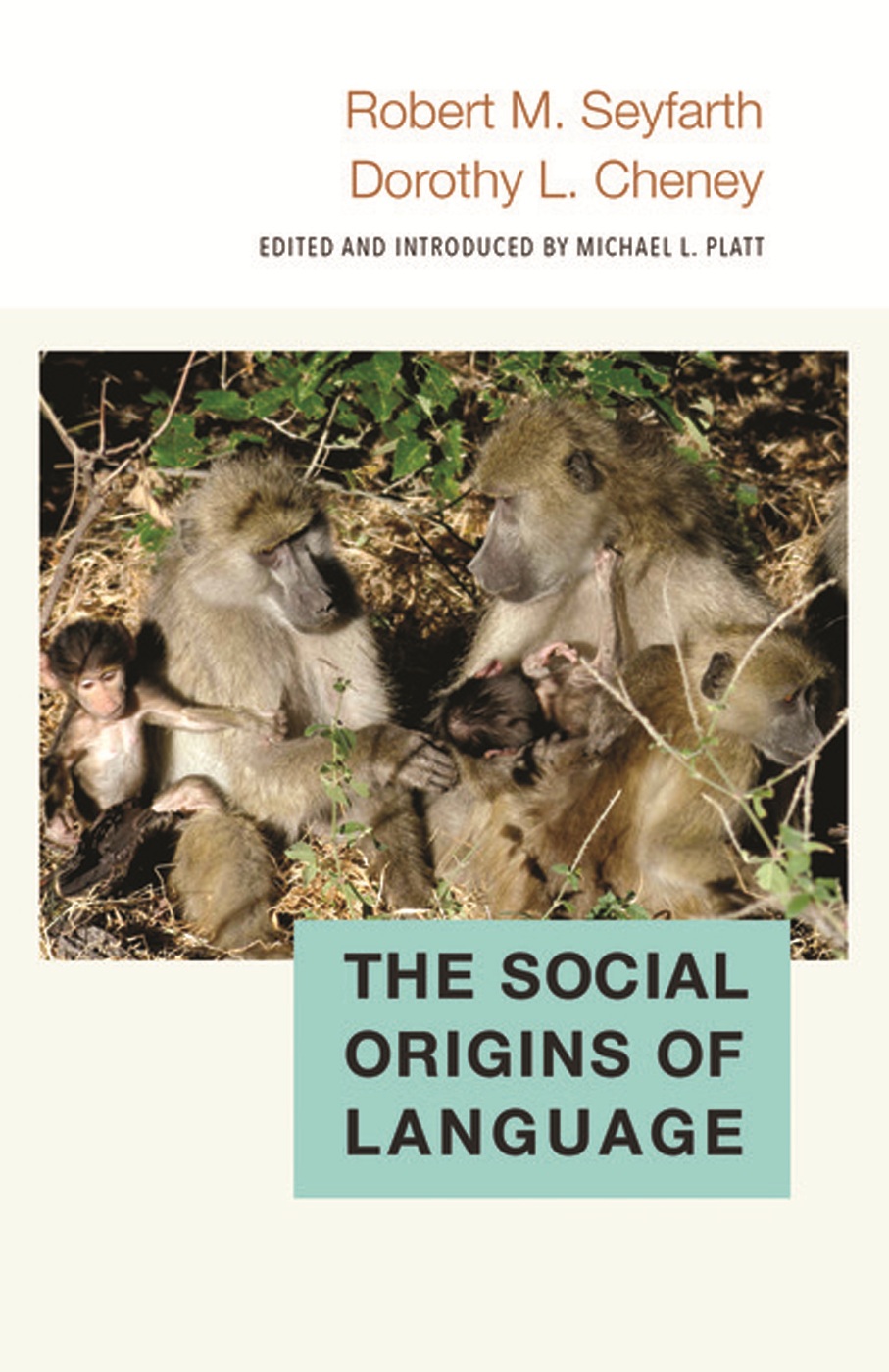

Cover photo by Dorothy L. Cheney

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17723-6

Library of Congress Control Number 2017952280

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

Michael L. Platt |

Robert M. Seyfarth and Dorothy L. Cheney |

John McWhorter |

Ljiljana Progovac |

Jennifer E. Arnold |

Benjamin Wilson and Christopher I. Petkov |

Peter Godfrey-Smith |

Robert M. Seyfarth and Dorothy L. Cheney |

THE CONTRIBUTORS

Dorothy Cheney is Professor of Biology and Robert Seyfarth is Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. They have spent over 40 years studying the social behavior, cognition, and communication of monkeys in their natural habitat.

Michael Platt is Professor of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Marketing at the University of Pennsylvania, and Director of the Wharton Neuroscience Initiative. Michaels work focuses on the biological mechanisms underlying decision making and social behavior, development of improved therapies for treating impairments in these functions, and translation of these discoveries into applications that can improve business, education, and public policy.

John McWhorter specializes in language change and contact and teaches linguistics at Columbia University. He has written The Power of Babel, Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue, Words on the Move, and other books on language, including the academic books Language Interrupted and Defining Creole.

Ljiljana Progovac is a linguist, with research interests in syntax, Slavic syntax, and evolution of syntax, and is currently professor and director of the Linguistics Program at Wayne State University in Detroit. Among other publications, she is the author of Evolutionary Syntax (Oxford University Press, 2015) and Negative and Positive Polarity (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Jennifer Arnold is a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and received her Ph.D. from Stanford University. She studies the cognitive mechanisms of language use in both adults and children, examining how language is used and understood in social and discourse contexts.

Benjamin Wilson is a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellow in the Laboratory of Comparative Neuropsychology at the Newcastle University School of Medicine. His research focuses on understanding the neurobiological systems that support language, and the evolution of these brain networks. His work combines a range of behavioral and neuroscientific techniques to investigate the extent to which cognitive abilities underpinning human language might be shared by nonhuman primates, and how far these abilities are supported by evolutionarily conserved networks of brain areas.

Christopher I. Petkov is a professor of neuroscience at the Newcastle University School of Medicine. His research is guided by the notion that information on how the human brain changed during its evolutionary history will be indispensable for understanding how to improve treatments for human brain disorders. His Laboratory of Comparative Neuropsychology uses advanced imaging and neurophysiological methods to study perceptual awareness and cognition, with an emphasis on communication, in particular auditory and multisensory communication.

Peter Godfrey-Smith is Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney, Australia. His main research interests are the philosophy of biology and the philosophy of mind, though he also works on pragmatism and various other parts of philosophy. He has written five books, including the widely used textbook Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (Chicago, 2003) and Darwinian Populations and Natural Selection (Oxford, 2009), which won the 2010 Lakatos Award. His most recent book is Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2016).

THE SOCIAL ORIGINS OF LANGUAGE

INTRODUCTION

MICHAEL L. PLATT

In the beginning was the Word.

Genesis 1:1

Or perhaps it was the grunt. The origins of human language, arguments from religion notwithstanding, remain hotly debated. From a scientific standpoint, human language must have evolved. As the great biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky said: nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution (Dobzhansky 1973). Yet, so far, evolutionary accounts have largely failed to provide a comprehensive explanation for why and how human language could have emerged from the communication systems found in our closest primate cousins. This dilemma reflects the fact that communication in human language arises from the union of semanticswords have referentsand syntaxwords can be combined according to a set of rules into phrases and sentences capable of generating countless possible messages. Put simply, there is no single nonhuman animalprimate or otherwisewhose natural communication system possesses both semantics and syntax.

This apparent discontinuity has led some (Berwick and Chomsky 2011; Bolhuis et al. 2014) to propose that human language appeared fully formed within the brain of a single human ancestor, like Venus springing from the head of Zeus, solely to support self-directed thought. Only later, according to this view, after language was passed down to the offspring of this Promethean protohuman, did language become a tool for communication. This solipsistic account, however, ignores emerging evidence for continuity in cognitive functions, like episodic memory (Templer and Hampton 2013), decision-making (Santos and Platt 2014; Pearson, Watson, and Platt 2014; Santos and Rosati 2015), empathy (Chang, Garipy, and Platt 2013; Brent et al. 2013), theory of mind (Klein, Shepherd, and Platt 2009; Drayton and Santos 2016), creativity and exploration (Hayden, Pearson, and Platt 2011; Pearson, Watson, and Platt 2014), counterfactual thinking (Hayden, Pearson, and Platt 2009), intuitive mathematics (Brannon and Park 2015), self-awareness (Toda and Platt 2015), and conceptual thinking (MacLean, Merritt, and Brannon 2008), and the neural circuits that mediate these functions (Platt and Ghazanfar 2010)though, to be sure, other discontinuities remain, in particular the ability to refer to the contents of representations (so-called ostensive communication or metarepresentations: Sperber and Wilson 1986; Sperber 2000). Despite growing appreciation for cognitive and neural continuity between humans and other animals, an evolutionary account of human languagein its full-blown, modern formremains as elusive as ever.

Next page