Flags are in use at sea by all kinds of vessel, from working ships to warships to yachts, both sail and power. There is a difference between the use of flags on land and at sea. Much of what follows in this book applies to flags wherever they are used afloat and also when hoisted on shore in a maritime connection. However, there is considerable emphasis on yachts and small working craft. Navies and shipping lines have their own regulations and practices and they are unlikely to need the advice given here. Yachts, motorboats and other small craft are, to some extent, on their own in this field. This little handbook is intended to provide their crews with a quick and ready reference for the use of flags at sea and on the shoreline.

There are technical implications to certain words in the English language used when flags, or colours, are shown. These words include fly and wear. Strictly speaking, a ship or boat wears a flag and the mariner flies a flag. Other terms such as display, hoist, show, and rig are also used but for easy reading they should be considered more or less interchangeable. The word yacht here, unless specified, can be taken to mean either a sailing or motor yacht.

Grateful thanks are extended to Commander R Porteous RN; Warrant Officer 1(C) Dave Allport (Yeoman of The Admiralty); Graham Bartram of The Flag Institute; Michael A Faul, Editor of Flag Master magazine; Mike Weston, John Bazley and the librarians at the Warsash School of Maritime Studies; Natasha Brown at the International Maritime Organisation; and Darren Wall at the Institute of Maritime Law, University of Southampton.

Flags have been in use for a very long time. The Romans hung textiles from crossbars and raised spears decorated with patterns and devices and we have all been doing much the same ever since.

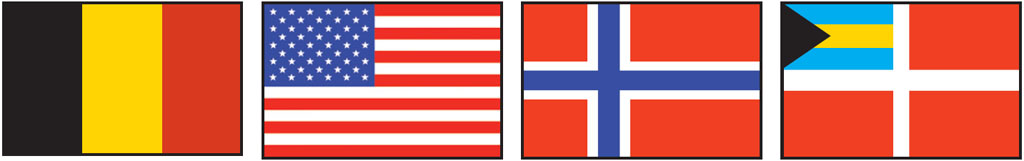

When Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, the first thing he did was to erect the Stars and Stripes. It is said that he even stiffened the top edge to stop it drooping on the windless planet. Nobody watching television anywhere on Earth could have been left in any doubt that (a) somebody had landed on the moon, and (b) judging by the flag, they were American. The flag crossed all language barriers.

So flags provide a picture but not always a welcome one. Every so often a flag representing an invading nation is burned in the streets of an occupied territory. The images are flashed around the world and it is clear that the locals dont like the visitors. Flags can be loaded with significance and arouse strong passions.

In the UK in 1997, following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, an outcry arose in the popular press that the royal standard above the monarchs residence should be flown at half mast. Other flags around the country had been half-masted. The authorities pointed out that the royal standard signifies the sovereign and is always flown fully hoisted. Even when a king or queen dies, the royal standard is not half-masted because, on the death of the monarch, he or she is instantly succeeded by his or her heir. The standard therefore immediately represents the new head of state. Such explanations fell on deaf ears with the tabloid press, which was determined to pursue this story. Quite a clever compromise was reached whereby a different flag (actually the Union flag) was hoisted on the mast which, until then, had displayed the royal standard. This second flag was then lowered to half mast instead and the royal standard, wilfully misunderstood by the people, was removed from the fray. This relatively recent, quite serious problem for the British monarchy shows that flags can still raise considerable emotion and anger.

Their usage and meaning varies, depending on whether or not they are ashore or afloat. When flags are shown at harbour offices, seamens training schools, lifeboat houses and yacht clubs, the practice followed is, as far as practicable, the same as on board ship. Mostly flag etiquette has been laid down by one navy or another and small craft skippers, such as ourselves, have inherited it. Sometimes we use it and sometimes we dont. Some of it is a matter of etiquette, some of it is antiquated, but quite a lot of it is still in current use. More important though is that some flag lore has become enshrined in international law and if nothing else you do at least need to know your legal obligations.

Customs and traditions of the sea

Most flag use at sea is derived from custom and tradition. Sometimes it is voluntary, often it is vague. It varies from one country to another, and some countries get much more upset about their flags than others.

Professional ships have their own traditional usage. Yachts should consult almanacs or follow club rules. There are various flag websites (listed in the ) and the Royal Yachting Association and Cruising Association are a mine of information for those going abroad. Generally, it is wise to avoid extraneous flags, pennants and ensigns. They are likely to be wrong, and others may strain to identify a signal that is meaningless. Other customs and traditions cover not only the flag itself, but also when, how, and where it is hoisted.

So this book is for those of you who dont really care very much what you fly, but sometimes need to know, and for those who do care what you fly and want to get it right.

Flags for use at sea are widely available from manufacturers, ship and yacht chandlers and websites. Special ensigns are usually ordered through their particular yacht club.

Seagoing flags are nowadays made of woven or knitted polyester, which dries quickly and is hard-wearing. The design is either dyed into the fabric then stitched to hold each separate colour component, or simply printed on. Printed flags look and are cheap. Obviously if you leave a flag to fly day and night you will shorten its life. Dirty, tatty flags look terrible and should be replaced.

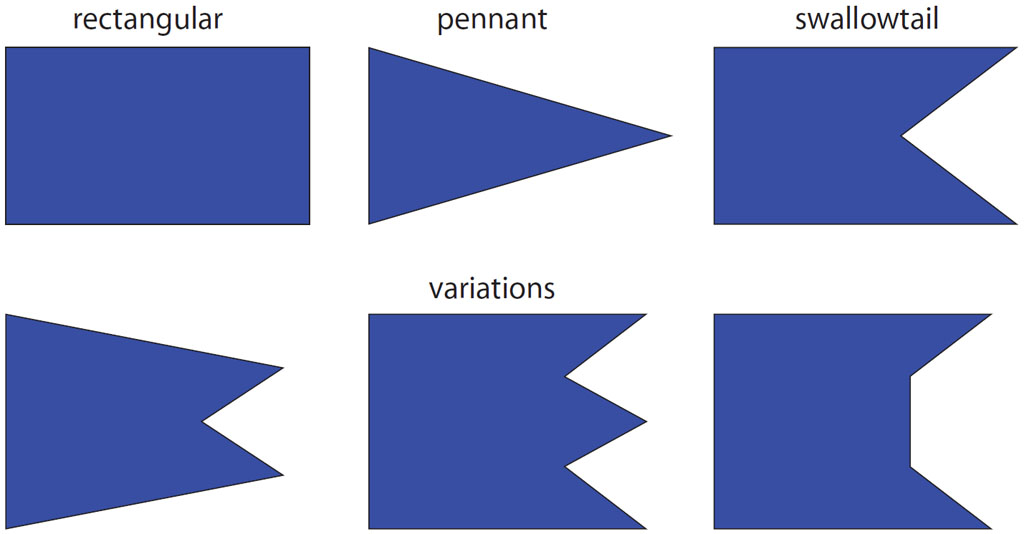

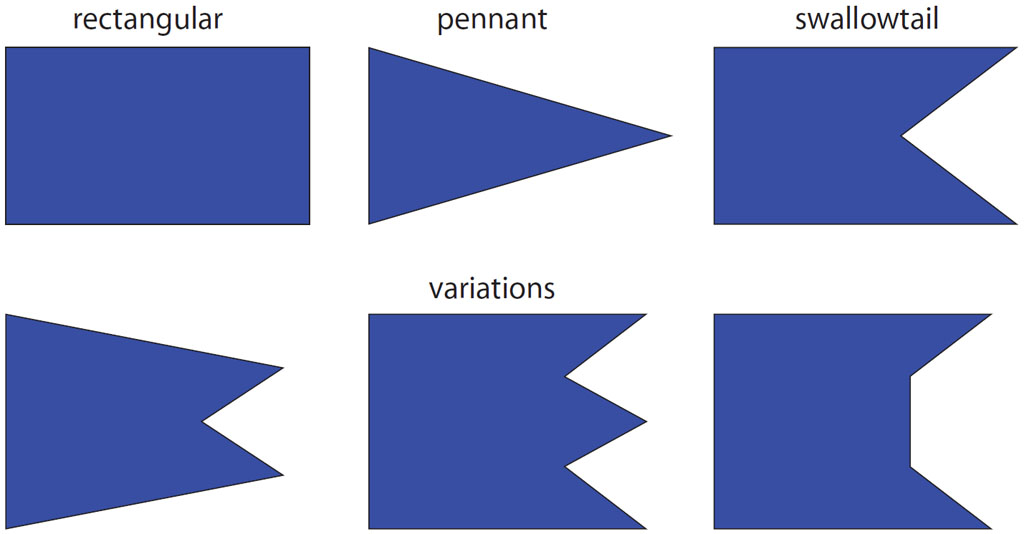

Three shapes are common in sea flags: rectangular (which includes square, but that is unusual), swallowtail and pennant ().

Fig 1 Shapes.

The pennant (or pendant) is triangular, but there are naval and other pennants which are much longer and closer in shape to streamers. The swallowtail is a rectangle with the end cut out. There are variations of this such as a sloping top and bottom so that it is more like a pennant with the end cut. More subtle is a flat inner corner accommodating a stripe (Danish naval ensign). There can also be rare multiple tails, again found in Scandinavia.

A flag has technical names for its various areas and edges. On a rectangular flag the dimension of the long side is called the length; the dimension of the short side (against the flag pole) is the breadth or the hoist. The top edge can also be called the head. The bottom edge can be called the bottom or the foot (as on a sail). The part flapping in the breeze is the fly. A section of the flag to which reference will frequently be made in this book is the canton. This is the upper corner nearest the point of suspension. Usually it consists of a quarter of the flag. Field or ground describes the background colour of the flag.