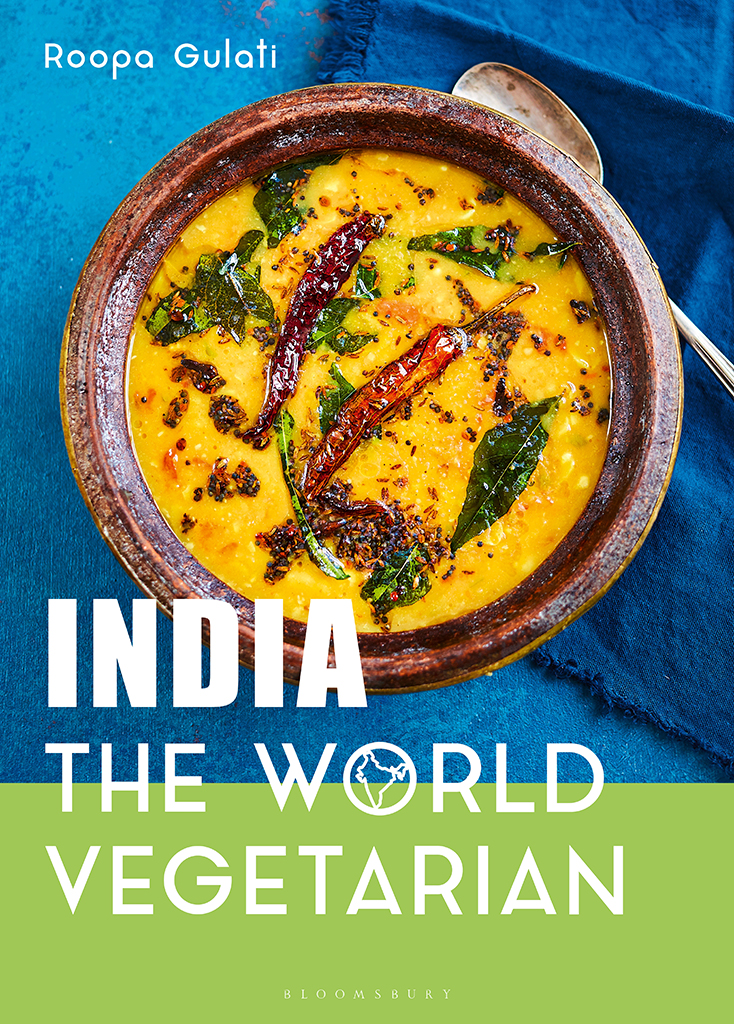

Roopa Gulati - India: The World Vegetarian

Here you can read online Roopa Gulati - India: The World Vegetarian full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1989, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

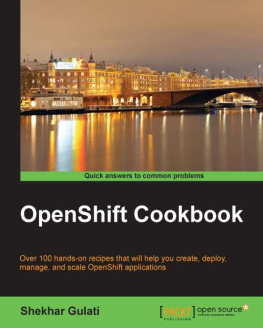

- Book:India: The World Vegetarian

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:1989

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

India: The World Vegetarian: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "India: The World Vegetarian" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

India: The World Vegetarian — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "India: The World Vegetarian" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Dan and our Friday night suppers.

INTRODUCTION

Regional Indian cooking is unrivalled for its breadth of flavours, textures and diversity.

Whether meals are enjoyed on silver thalis, banana leaves or palm leaf plates, what we eat provides us with a blueprint of belonging and identity.

The countrys varied landscapes include the fertile plains of Punjab in north India, where crisp ghee-laden layered parathas, tarka dal and simple cumin-spiced vegetables are staples. Then theres the arid, desert-like climate of Rajasthan, where nature has been less kind. But its seemingly meagre resources are compensated for by culinary creativity, and many classic dishes are slow-cooked in yoghurt to conserve scarce water supplies.

Contrast this with south Indias palm-fringed coastline and verdant spice gardens. An everyday masala in Kerala might feature mangoes or pineapple, folded into simmering coconut milk, spiked with the crackle of curry leaves, popped mustard seeds and sizzling red chillies. Its all change across the north east, where dishes are cooked in pungent mustard oil and often spiced with the regions signature blend of panch phoran. This heady mix of whole fennel, fenugreek, cumin, nigella and mustard seeds, is dropped into hot oil, where it releases a sweet-astringent pickled flavour, such as in Bengali chutney.

Around 70 per cent of Gujaratis are vegetarian and savoury dishes, including dals, are marked by sweet jaggery and tart tamarind as key flavours. There are at least 60 types of lentils and pulses used across India and its easy to be overwhelmed by the variety. But dals are forgiving and open to interpretation most home cooks dont even bother with a specific recipe. For a country shaped by dietary preferences and regional likings, the sheer range of dishes based on the humble lentil commands nothing but respect. Theres usually a pot of daily dal on the go in most kitchens, but lentils and pulses are also a valuable base for fried snacks, such as pakoras, savoury doughnuts and crepe-like pancakes. A little leftover dal can even be kneaded into chapati dough to enrich and add texture and an earthy flavour to the bread, before it is cooked on a griddle.

Some vegetarian communities, such as the Jains, dont eat onion or garlic, as they believe that these ingredients heat the blood and promote impure thoughts. They follow the philosophy that digging up vegetables from the ground could injure insects and other living creatures, and their tenet is to do no harm to life. Strictly speaking, orthodox Jains wont even eat root vegetables or tubers, so potatoes would be swapped for plantains and even turmeric would be off-limits. Jains are famed for their imaginative recipes and have honed a vibrant cooking style, which incorporates such spices as umami-like asafoetida and tangy mango powder, bringing big flavours to everyday vegetables.

Dairy produce plays a central role in the Indian vegetarian kitchen. Milk-based dishes are offered to the deities in temples across north and central India, and also have auspicious connotations at celebrations. Dishes cooked in pure ghee are also seen as an indicator of wealth and indulgence.

Sharing culinary know-how is a largely oral tradition with huge regional variations on how best to cook family favourites. Definitive recipes are few and spice blends vary across the country and even within families. Traditionally, a mother-in-law passed prized recipes to her daughter-in-law rather than her own daughter, because, after marriage, the daughter would be cooking a new set of heirloom recipes belonging to her husbands family. Even today, the kitchen continues to be a source of influence, especially in large extended families where recipes are retained and respectfully valued.

Chillies are integral to Indian cooking; today, India is the largest producer of chillies in the world but its worth noting that it was the Portuguese who brought them from the Americas to India in the 16th century. The Portuguese also introduced garlic, tomatoes and potatoes from the New World to Goa on the western coast. Today, there are dishes, which have been adopted and then adapted from the Portuguese, such as the famed vindaloo with its garlicky-vinegary masala and abundance of dried red chillies.

The Mughals introduced India to Persian dishes in the 16th century and left behind a lasting culinary legacy, which combined Middle Eastern flavours with local Indian produce. Although they were best known for extravagant kebabs and meaty curries, there remains a small but carefully curated collection of vegetarian dishes, which often gets overshadowed. Their distinctive style of cooking embraced masalas made with pounded nuts, which were scented with complex aromatic spices. This two-way exchange of ideas found favour with vegetarian Hindus, who developed a taste for rich culinary indulgence and incorporated such spices in their own cooking. In addition to the Persian and Portuguese influences in shaping the countrys cooking, Britain, France, the Netherlands and Southeast Asia have had greater or lesser roles in the evolution of its culinary history.

In return, Indias greatest export has to be its cooking. From curry houses on the high street, to pop-up cafs and fine dining establishments theres barely a country on this planet that doesnt fly the flag for all things masala.

Although a few Western vegetarian dishes still feature on colonial-style menus in India, they tend to favour the likes of baked vegetables cloaked in bchamel sauce, where the wildest spice used is a pinch of white pepper. Historically, Indian cooks triumphed in enlivening colonial offerings, by adding raunchy garlic, ginger and chillies to roasts, toasted spices in soups and even pounded chillies over potato chips. Its these dishes that have been cherished over the years. Chilli cheese toast is one such legacy, which is as likely to be found on a club bar menu as in a home kitchen.

Despite the recent popularity of international fast food chains in India, traditional street stalls continue to draw in the crowds. Some snacks are a mix of hot and cold items, such as warm potato cakes, surrounded by yoghurt and topped with herby chutney. Others, such as bhel puri and fruit chaat are served at room temperature and major on tart-tangy flavours. Chickpeas and potatoes are especially obliging for carrying sauces, roasted spices and creamy yoghurt.

Perhaps no other snack encapsulates Indias heritage than the samosa. Samosas are said to have originated in the Middle East and early references can be traced back to the 10th and 11th centuries, when they were described as sambuskan. These snacks were easy to carry on long journeys and were popularised by Arab merchants travelling to India on the old Silk Route. They were also probably brought over by maritime traders. Meat-filled samosas were a feature of Mughal banquets, but after the introduction of potatoes by the Portuguese in the 16th century, vegetarian Hindus quickly adapted these for fillings and made them their own. The list of samosa fillings is limited only by our imagination, but a good starting point is the classic potato and pea filling favoured by hawkers in the bazaars of the old quarters of Indian cities.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «India: The World Vegetarian»

Look at similar books to India: The World Vegetarian. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book India: The World Vegetarian and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.