The future of healthcare is in the hands of children. India has a huge child population, talented and brilliant, and they can become the providers and caregivers to the nation and the world. Indian doctors are very popular across the world for their empathy and compassionate care.

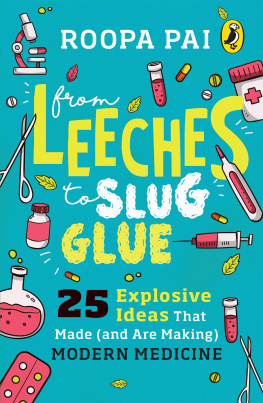

Roopa Pai has come out with yet another magnificent piece of work, this time covering the history of medicineoccidental and oriental. The book develops into twenty-five fascinating chapters of gripping narrative on modern medicine, surgery, pathology, nutrition and genetics, interspersed with interesting bits of facts. I am sure young minds will be piqued and inspired, by the contents of this book, to take up the medical profession, while even adults will find it informative. Dr Devi Shetty

I Dont Want to be a Doctor.

Why Should I Read This Book?

It isnt the funnest thing in the world to be ill, of course, but there are always compensations. The biggest, fattest silver lining for us who fall ill in the twenty-first century is, well, exactly thatweve fallen ill in the twenty-first century!

No, seriously. If you had lived even as recently as 200 years ago, you might have received some pretty bizarre, and/or very painful, treatments for your condition.

A physician / barber surgeon (more details given in the box on page xii) may have:

- unleashed a whole army of leeches on you, so that they could suck out your bad blood (be warned, this treatment hasnt fallen entirely out of favour, is reputed to have many benefits and may yet make a big comeback);

- drilled a hole into your skull, via a procedure called trepanning, to let the evil spirits out (not even kidding; also, just FYI, to spare you some really scary nightmares, this procedure isnt life-threatening);

- amputated a limb because it was infectedwithout using anaesthesia (because an effective mixture for numbing pain that didnt send the patient into fatal shock hadnt yet been testedouch!) and while using surgical instruments that looked more like medieval torture devices than anything else (maybe that was part of the strategypatients probably passed out from sheer terror the moment they caught sight of the instrument, thus precluding the need for any other kind of knockout drug);

- wrapped you up like a mummy, plunged you into an ice-cold bath and kept you there for hours at a time to treat your manic episodes, chained you up and restrained you in a straitjacket for days on end to prevent you from hurting yourself, or conducted a lobotomy on you (taken out bits of your brain that they believed to be responsible for madness)all in an effort to cure you of your insanity, which was believed to be a result of demonic possession.

Say whaaaa...?

Barber surgeon? Yes! In Europe, for a big part of the last thousand years, barbers doubled as surgeons, simply because they were skilled at using sharp tools. Uh-huh. Thank goodness butchers werent given that honour.

But spare those poor physicians a thought. None of them did what they did because they were particularly mean or sadisticall their treatments were done in good faith, and came out of long-held (and as we know now, erroneous) beliefs about what made us ill. Hardly anyone back then understood any aspect of mental illness, and although the treatments have become far more humane now, and great progress has been made, we are still quite some way from truly understanding howor how much!the brain is related to the mind. Physical illness, and how the body worked, was better understood, but treatments were often misguided simply becauseget this!until the 1880s, very few people in the world believed, or even suspected, that it was germs that caused disease!

Astounding as it sounds, so many things that we take for granted today about disease and treatment are very, very new developments in the history of humankind. Medicine is arguably the worlds youngest science, and seen from that perspective, the massive strides it has made towards understanding and healing the human body (and mind) are nothing short of, um, mind-blowing. We are better-nourished, die far less often from infectious diseases and live way longer as a species today, almost entirely because of advances in modern medicine.

What are some of these eye-popping advances over the last two centuries? Well, among a great many other things, we have:

- almost entirely eradicated some terrible diseasessmallpox, measles, poliofrom our midst, and learnt how to isolate and control the spread of epidemics like cholera and plague which used to wipe out entire populations in the past;

- extended the average lifespan of human beings to almost double of what it was 150 years ago. Yup, in 1880, the average life expectancy at birth was forty years; today it is closer to eighty. Even in India, where the population is over 1.2 billion, and where a small minority has the money and opportunity to access nutritious food, clean drinking water and good medical care, the average life expectancy today is 66.9 years for a male and 69.9 years for a female. (By the way, this difference in life expectancy between men and women isnt unique to Indiaacross the world, statistically speaking, women live longer than men.);

- succeeded in cloning animals (And what is cloning? The process of creating an animal that is genetically identical to another in a non-traditional way, i.e., without fusing sperm and egg. Can you imagine what this technology could do to help revive populations of creatures on the verge of extinction?);

- developed the ability to 3D-print body parts for transplants or replacements. In the future, this will eliminate the long and often fatal wait for organs (for those who need them), and help create hearing aids and prosthetic limbs to perfectly fit your individual ear shape and body type;

- learnt how to tweak things at the DNA level to prevent hereditary diseases from being carried forward instead of treating those diseases after they have showed up. Gene therapy, for thats the name of this still experimental game, has also had some early success in strengthening the immune system and reversing certain kinds of fatal cancers;