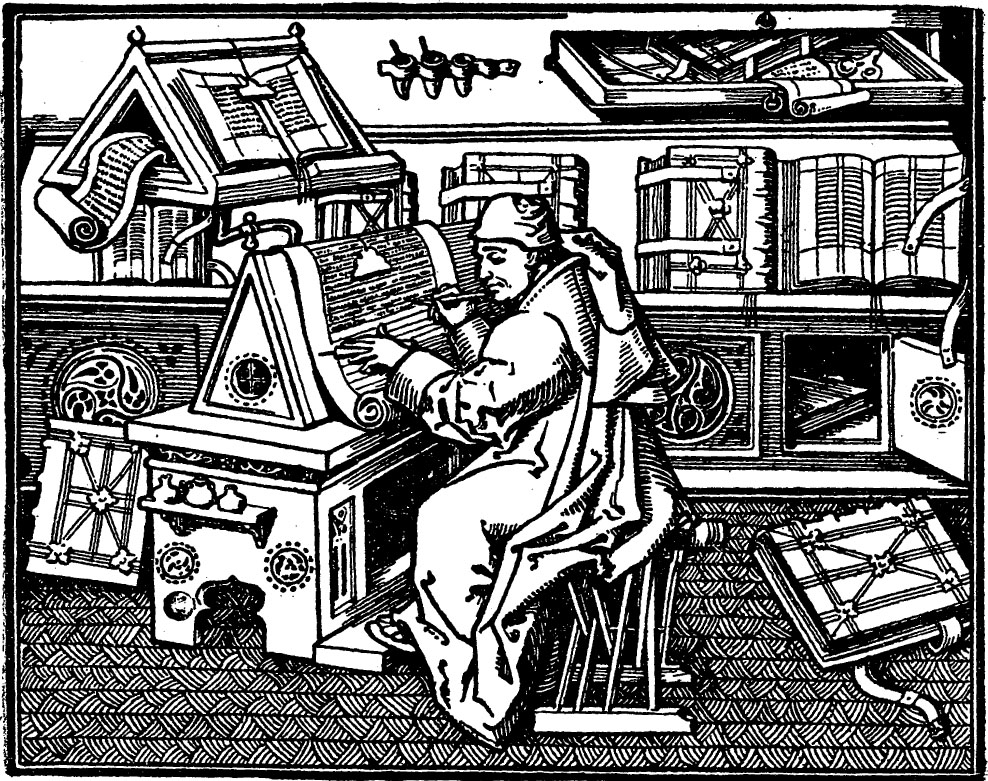

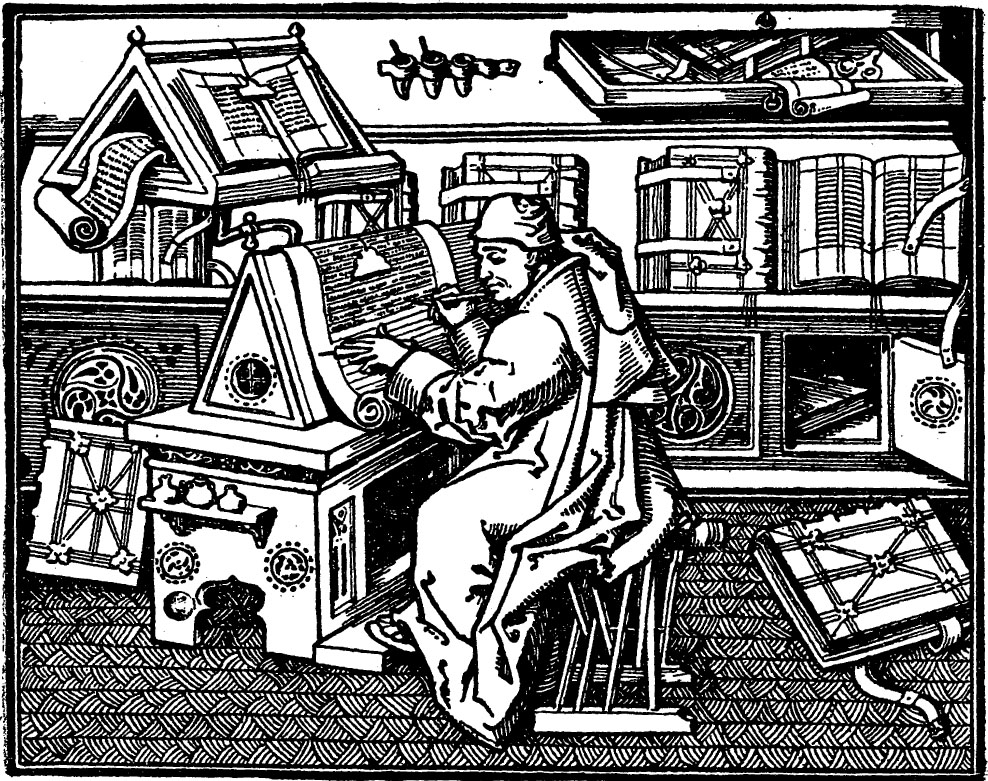

Frontispiece

A SCRIPTORIUM

This drawing (about two-fifths of the linear size of the original) is made from a photograph of a miniature painted in an old MS. (written in 1456 at the Hague by Jean Mielot, Secretary to Philip the Goody Duke of Burgundy), now in the Paris National Library (MS. Fonds franais 9,198).

It depicts Jean Mielot himself, writing upon a scroll (said to be his Miracles of Our Lady). His parchment appears to be held steady by a weight and also by (? the knife or filler in) his left handcompare fig. in this book Above there is a sort of reading desk, holding MSS. for copying or reference.

WRITING & ILLUMINATING & LETTERING

With 250 Illustrations

Edward Johnston

Illustrated by

the Author and Noel Rooke

Dover Publications, Inc.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1995 and reissued in 2017, is an unabridged republication of the 1946 printing (Twenty-first Impression) of the 1939 revision, published by Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd., London, of the work originally published in 1906 by John Hogg, London, in The Artistic Crafts Series of Technical Handbooks Edited by W. R. Lethaby. For the present edition, eight pages that originally appeared in black and red have been reproduced here in black and white.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johnston, Edward, 1872-1944.

Writing & illuminating & lettering / Edward Johnston ; illustrated by the author and Noel Rooke.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : I. Pitman, 1946.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-28534-4

ISBN-10: 0-486-28534-0

1. Lettering. 2. Illumination of books and manuscripts. I. Title. II. Title: Writing and illuminating and lettering.

NK3600.J6 1995

745.6dc20

94-46428

CIP

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

285340032017

www.doverpublications.com

EDITORS PREFACE

IN issuing these volumes of a series of Handbooks on the Artistic Crafts, it will be well to state what are our general aims.

In the first place, we wish to provide trustworthy text-books of workshop practice, from the points of view of experts who have critically examined the methods current in the shops, and putting aside vain survivals, are prepared to say what is good workmanship, and to set up a standard of quality in the crafts which are more especially associated with design. Secondly, in doing this, we hope to treat design itself as an essential part of good workmanship. During the last century most of the arts, save painting and sculpture of an academic kind, were little considered, and there was a tendency to look on design as a mere matter of appearance. Such ornamentation as existed was usually obtained by following in a mechanical way a drawing provided by an artist who often knew little of the technical processes involved in production. With the critical attention given to the crafts by Ruskin and Morris, it came to be seen that it was impossible to detach design from craft in this way, and that, in the widest sense, true design is an inseparable element of good quality, involving as it does the selection of good and suitable material, contrivance for special purpose, expert workmanship, proper finish, and so on, far more than mere ornament, and indeed, that ornamentation itself was rather an exuberance of fine workmanship than a matter of merely abstract lines. Workmanship when separated by too wide a gulf from fresh thought that is, from designinevitably decays, and, on the other hand, ornamentation, divorced from workmanship, is necessarily unreal, and quickly falls into affectation. Proper ornamentation may be defined as a language addressed to the eye; it is pleasant thought expressed in the speech of the tool.

In the third place, we would have this series put artistic craftsmanship before people as furnishing reasonable occupations for those who would gain a livelihood. Although within the bounds of academic art, the competition, of its kind, is so acute that only a very few per cent can fairly hope to succeed as painters and sculptors; yet, as artistic craftsmen, there is every probability that nearly every one who would pass through a sufficient period of apprenticeship to workmanship and design would reach a measure of success.

In the blending of handwork and thought in such arts as we propose to deal with, happy careers may be found as far removed from the dreary routine of hack labour as from the terrible uncertainty of academic art. It is desirable in every way that men of good education should be brought back into the productive crafts: there are more than enough of us in the city, and it is probable that more consideration will be given in this century than in the last to Design and Workmanship.

......

Of all the Arts, writing, perhaps, shows most clearly the formative force of the instruments used. In the analysis which Mr. Johnston gives us in this volume, nearly all seems to be explained by the two factors, utility and masterly use of tools. No one has ever invented a form of script, and herein lies the wonderful interest of the subject; the forms used have always formed themselves by a continuous process of development.

The curious assemblages of wedge-shaped indentations which make up Assyrian writing are a direct outcome of the clay cake, and the stylus used to imprint little marks on it. The forms of Chinese characters, it is evident, were made by quickly representing with a brush earlier pictorial signs. The Roman characters, which are our letters to-day, although their earlier forms have only come down to us cut in stone, must have been formed by incessant practice with a flat, stiff brush, or some such tool. The disposition of the thicks and thins, and the exact shape of the curves, must have been settled by an instrument used rapidly; I suppose, indeed, that most of the great monumental inscriptions were designed in situ by a master writer, and only cut in by the mason, the cutting being merely a fixing, as it were, of the writing, and the cut inscriptions must always have been intended to be completed by painting.

The Rustic letters found in stone inscriptions of the fourth century are still more obviously cursive, and in the Catacombs some painted inscriptions of this kind remain which perfectly show that they were rapidly written. The ordinary lower case type with which this page is printed is, in its turn, a simplified cursive form of the Capital letters. The Italic is a still more swiftly written hand, and comes near to the standard for ordinary handwriting.

All fine monumental inscriptions and types are but forms of writing modified according to the materials to which they are applied. The Italian type-founders of the fifteenth century sought out fine examples of old writing as models, and for their capitals studied the monumental Roman inscriptions. Roman letters were first introduced into English inscriptions by Italian artists. Torrigiano, on the tombs he made for Henry VII in Westminster Abbey and for Dr. Young at the Rolls Chapel, designed probably the most beautiful inscriptions of this kind to be found in England.

This volume is remarkable for the way in which its subject seems to be developed inevitably. There is here no collection of all sorts of lettering, some sensible and many eccentric, for us to choose from, but we are shown the essentials of form and spacing, and the way is opened out to all who will devote practice to it to form an individual style by imperceptible variations from a fine standard.

Next page